Christopher Moriarty

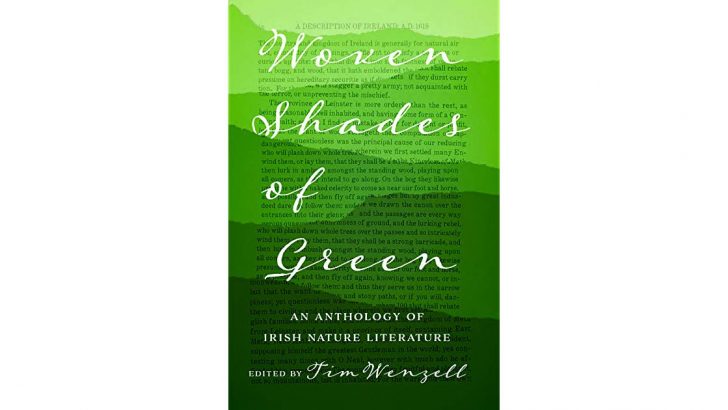

Woven Shades of Green: An anthology of Irish nature literature

by Tim Wenzell (Bucknell University Press / distributed by Rutgers University Press, $US29.95/£24.95)

As one of the many writers on Irish nature who is not included in this anthology, I have to declare an interest. The preface indicates that the omission of knowledgeable writers occurs as a result of the editor’s intention to demonstrate the lack of interest in nature of Irish people in general.

By ‘literature’ he means poetry, drama and the like in contrast to the works of those who actually study the subject and write to communicate their observations for the benefit of a wider readership.

This approach might well be of interest, and even value, if the editor’s purpose were simply to show how people other than naturalists observe and describe nature. But the copious commentary on the selected writings indicates that he is deeply concerned with the wholly admirable topic of nature conservation and wishes to tell the world of what he sees as shameful neglect.

Humour

This writing in not without its unintentional humour. On the first page of the preface he offers the following quotation by a well-known journalist: “It’s quite clear to me that by 2020 this country will be completely destroyed.” A footnote indicates that this prophetic statement was made in 2004.

As I commute towards the city of Dublin through the suburbs and amidst a scene of purple mountains and extensive green space, very much the same as it has been for 40 years, if slightly much changed in the past 20, I wonder where the destruction lies.

Yes, the environment-alists’ bugbear of ‘urban sprawl’ exists – but not on the scale implied by this kind of writing. What is even more regrettable than his use of this strident material is the editor’s virtual exclusion of reference to the marvellous work in progress for some decades in the creation of parks, the setting aside of immense areas for conservation by a host of dedicated workers, and the very remarkable increase in concern for the environment on the part of politicians and public servants.

A goodly selection of prose, poems and brief excerpts of drama make it a pleasure to dip into”

Also missing are a number of extremely important authors whose work makes it very clear that many Irish people through the ages had a highly sophisticated knowledge and understanding of various aspects of nature.

The 6th-Century author known as ‘The Irish Augustine’ listed the furry creatures of his country and wondered how they reached the island after Noah’s Flood. He concluded that land masses evolve and Ireland must once have been attached to the continent.

Then came the Welsh visitor Gerald de Barri in the 12th Century who provided a description of Ireland so precise that it would not have been possible for him to make many of the observations himself. They can only have come from observant natives. And perhaps above all is the 17th Century Roderic O’Flaherty of Galway, the writer of an erudite and masterly description of nature and man in Iar-Connacht.

These omissions are extremely serious and greatly reduce the value of the book. But what remains? A goodly selection of prose, poems and brief excerpts of drama make it a pleasure to dip into and brings together a satisfying number of old favourites and occasional little-known gems of nature writing.

It seems to provide a suitable text for ‘green readings’ in the area of Irish studies that is now endemic – and growing – in the US.

Woven Shades of Green: An anthology of Irish nature literature

Photo: goodreads

Woven Shades of Green: An anthology of Irish nature literature

Photo: goodreads