Ian D’Alton

County Louth and the Irish revolution 1912-1923

edited by Donal Hall and Martin Maguire (Irish Academic Press, €19.99 pb, €39.99 hb).

In this ‘decade’ of commemorating and remembering the formative period from 1912 to 1923 we are already buried in books. The centenary of the 1916rebellion has seen the emergence of literally hundreds of works, eclipsing the not inconsiderable output in 1966. 2017 promises to be a relatively barren year, but 2018 to 2023 carries the promise, or threat, of much more. So, is there room for yet another?

In the case of Hall and Maguire’s edited collection of 13 essays, the answer is an emphatic yes. This is for two principal reasons. The first is that it covers the entire so-called revolutionary period, and thus has both perspective and narrative – characteristics that are frequently missing in more detailed and time-focused studies.

The second reason is that it is a local study, and thus has coherence and shape. In this period, of those who had stayed in Ireland, most seldom moved far from the locality in which they lived, worked, had families, died. The sense of connectivity of the lives that emerge from this book is one of its strengths.

The same people keep popping up in different contexts. As just one example, Peter Hughes, pro-Treaty TD for Louth-Meath and Minister for Defence, features in Donal Hall’s perceptive and informative introductory overview; in Ailbhe Rogers’ analysis of Cumann na mBan; in Brendan McAvinue’s essay on policing; in John McCullen’s on ‘William McQuillan of Drogheda: an unlikely rebel’; and in Conor McNamara’s important essay on political upheaval and sectarian violence in the 1920-22 period.

This last points up the fact that Louth was always a ‘border county’. It abutted the southern parts of Down and Armagh, always a tinder-box of tension.

In June 1922, six Protestants were murdered at Altnaveigh, Co. Down by elements of the 4th Northern Division of the Irish Volunteers under Frank Aiken. The Dunmanway, Co. Cork, killings of April 1922 have overshadowed this atrocity, yet its genesis was in part the same – the recent anti-Catholic pogroms in Belfast.

McNamara provides perspective to the Down massacre by looking at the war of independence in Louth through the prism of sectarian violence in the two years before Altnaveigh. He is even-handed in maintaining that “an authentic account…necessitates the restoration of the historical narrative of the deep loss suffered, and inflicted, by both communities and the inevitability of ethnic conflict in a divided society in a time of war”.

This should be a guiding text for the historians of the decade. The essays here are written by local enthusiasts as well as professional historians and academics. Hall and Maguire have done an excellent job of corralling these into a well-ordered, if eclectic, collection. It has the merit of being able to be read as a whole. But it can be dipped into as well.

If you are a railway buff, Peter Rigney’s piece on the railways of Louth, 1912-23, is for you. If the workings of the Big House – increasingly peripheral in this period – are your passion, then Jean Young’s essay is well-researched, adding another layer to Louth life.

Martin Maguire’s essay on the labour movement is a significant academic contribution to understanding that radicalism in the 1912-23 period was not just about the onward march and changing shape of political nationalism.

Using Louth as exemplar, Maguire shows that labour– urban and rural –also absorbed international influences from British trade unionism and pro-Russian socialism. He notes that at a 1919 May Day parade in Drogheda the Red Flag was flown rather than the Tricolor and that “Petrograd in 1917 was more significant than Dublin in 1916”.

This book is readable, empathetic and accessible. It elevates the unknowns, the ordinary men and women who were part of, or who tried to stay aloof from, the Irish revolution. It is precisely the ordinariness of the people here that puts living flesh on the stone bones of high politics and military dispositions.

The striking cover photograph is of an informal group of Irish Volunteers and Cumann na mBan, Dundalk, in 1921. More than any essay, this captures the forces that the revolution had the potential to let out of the box. Six women, two men, and a dog, lounge in a field. The women cradle rifles and cigarettes. One has a possessive arm across a man’s chest – his arm is around another girl.

Any priest or prelate seeing this louche group would have had apoplexy, probably. Political revolution was permissible, just about: the social and sexual revolution implied in this photograph was not. It had to be stamped out. And it was.

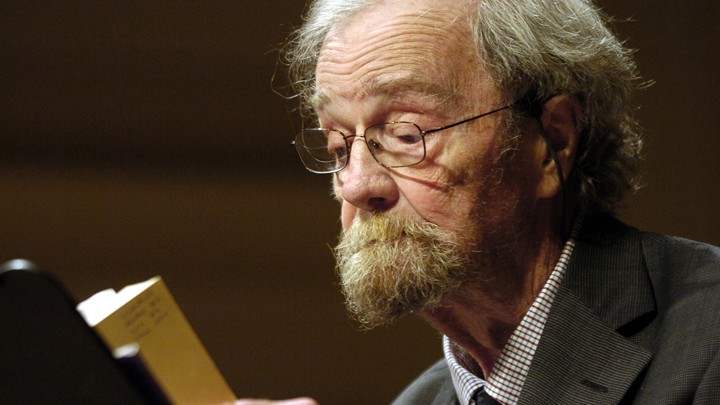

Donal Hall

Donal Hall