Bulwarks of Unbelief: Atheism and Divine Absence in a Secular Age

by Joseph Minich, foreword by Carl R. Trueman (Lexham Press, €25/ $29 / £21)

How did we, in the West, move from a world in which belief in God was the default position to one in which it is an option among others?

Charles Taylor’s The Secular Age (2007) is the most discussed study of the trajectory of thought that brings us to this point. Other philosophers have contributed, notably, Remi Brague, with his The Kingdom of Man: Genesis and the Failure of the Modern Project (2018 – original French version appeared in 2015).

Now, Joseph Minich, a teaching fellow at the Reformed Protestant, Davenant Institute enters the conversation with this valuable contribution.

Thoroughness

The secular age came to Ireland in a rush, spectacular in its thoroughness. Whatever about belief (69% report themselves as ‘Catholic’), the practice of religion has dived from 91% in 1975 to 30% in 2021. The voices of the Church have all but disappeared from the public sphere.

How has this come about? We can speak of push and pull factors. The latter is the vision of the human condition found in the Church with the promise of salvation, the former those aspects of the Church that repel.

Is it not possible that the decline of the pull of the vision towards commitment and practice preceded the scandals and the outrage?”

These appear to be the most significant in Ireland. How often do we hear people explain their detachment from the Church in terms of their revulsion at clerical sex abuse and its cover up, or the harsh, cruel treatment of women who transgressed its sexual norms?

That the truth, or plausibility of the vision is seldom, if ever, in the frame is not surprising. We Irish do not ‘do ideas’, anti-intellectualism being a distinctive feature of our culture.

Nonetheless, is it not possible that the decline of the pull of the vision towards commitment and practice preceded the scandals and the outrage? As the vision recedes, the institution loses respect and its sins are brought into daylight?

Minich is particularly helpful here. While more than able to engage with the philosophical dimension, he pays more attention to the socio-cultural dimension than either Taylor or Brague.

Interactions

Indeed, his ability to trace the interactions between the world we find ourselves in and our efforts to orientate ourselves within it, is one of the book’s greatest strengths.

And we find ourselves in a world very different from that of our parents or grandparents. What could be clearly seen in their horizon, is obscured in ours.

Not so long ago, cows grazed and crops grew around the small village of Leixlip, where the multinational company Intel now manufactures chips for computers. Some 4,500 work in the vast complex that covers 360 acres and represents an investment of €28 billion.

While its fruits were visible in what we can do and produce, its impact on how we envisage ourselves, our relationships with others, our place in the cosmos is just as significant”

How could one measure the distance of this world from that of the community of farmers that tended the cattle and tilled the land?

We did not choose this new world with all its ramifications and transformations, though it is of course the consequence of choices that we did make. The crucial choice was to find our way into the modern globalised economy, seeking its material benefits.

This world was a long time in the making. Technology was a dominant force. While its fruits were visible in what we can do and produce, its impact on how we envisage ourselves, our relationships with others, our place in the cosmos is just as significant.

Impact

Many philosophers and theologians have examined this impact, Minich pays special attention to two thinkers who have shaped the discussions. He gives us a lucid account of the work of Jacques Ellul (1912-1994) French philosopher, sociologist and lay theologian and the German philosopher, Martin Heidegger (1889 -1976) providing an analysis of the limitations of the ‘technoculture’ we now inhabit.

This world operates with an impoverished concept of reason. This ‘instrumental’ reason can give us more and more efficient and effective means for getting from A to Z, while leaving us bereft of reasons why Z could be a worthwhile destination. We assert values in the absence of any idea of the good.

The world presents us with a sharp distinction between the ‘subjective’ and the ‘objective’ that disengages us from nature. Working as instruments of production, we cannot identify ourselves in what we make, so we express ourselves in what we consume.God is absent from this world.

We must be grateful to the philosophers/theologians who use their God-given reason to guide us”

Minich concludes this fine book asking what its implications are for the believers who find themselves in this world.

He reminds us of St Augustine’s distinction between the ‘City of Man’ and the ‘City of God’. Christianity is an historical religion; the story of revelation, a long process of education, for the inhabitants of the ‘City of Man’ in what is the Kingdom whose coming they pray for.

We are in a chapter of that lesson. As the deficiencies of our technoculture become increasingly apparent in our politics, our economies, our efforts to save the planet, our relationships, it seems that we are starting a new chapter.

We must be grateful to the philosophers/theologians who use their God-given reason to guide us. Minich is eminent among them.

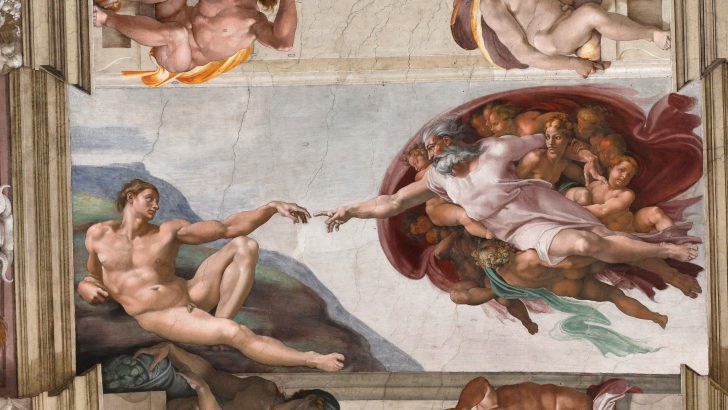

The Creation of Adam by Michelangelo Buonarroti is pictured in the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican Museums in this February 21, 2020, file photo. Photo: CNS

The Creation of Adam by Michelangelo Buonarroti is pictured in the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican Museums in this February 21, 2020, file photo. Photo: CNS