Part 1 of a new series on Faith in modern Ireland with Eoin McCormack

Have you ever found yourself in the often-awkward position at work or in other social settings where you are elected as the spokesperson for all things Catholic? As society continues to diverge from the Church, if you’re a practicing Catholic in modern Ireland, chances are that you have been in this position – and if not, now might be the time to prepare, because sooner or later you might be asked to justify your faith in some form or another. Over the next several weeks, this column will address many themes underlying the most commonly discussed topics regarding faith in modern Ireland and offer some tips and insights on how to engage with those challenging conversations.

Hostility

Situations like these which so many Catholics find themselves in, very often begin with the bewildered challenge – Are you religious? – As if you have some kind of embarrassing secret that you were hiding! Consistently, I am informed by people of faith about the increasing hostility they encounter in the secular workplace when they are ‘found out’ to be associated with the Catholic Church. Casual remarks have become commonplace in staff rooms and canteens that would be considered offensive and ignorant if spouted about other religions. Catholicism, however, seems fair game for throw-away comments which leave the contemporary faithful Catholic somewhat embarrassed or uncomfortable. It seems fair to say in modern Ireland, that familiarity with Catholicism has certainly bred contempt, or at least whatever misconceived version of Catholicism has done so.

Over the past several years working in parish ministry in Dublin City and listening to the unease that many young Catholics in particular encounter in the contemporary workplace, the question “How do I talk about my faith in public?” is becoming increasingly important. Whether it has become widely known amongst their friends or colleagues that they’re the ‘odd ball’ who continues to go to Church despite it all, or they’ve been labelled as the ‘Catholic one’ in the office, many Catholics in Ireland today very often find themselves ill-equipped to respond to the challenges posed to them about religion and faith. It is of no surprise therefore, that one of the top priorities that came from the laity in the recent Irish synodal process was the need for better adult faith formation.

The cultural situation demands equipping ourselves with confident apologetics to defend the hope within as St Peter instructs in the scriptures”

For Catholics in modern Ireland, devotional religion alone is no longer sufficient. The demands of the modern world require a much more rigorous intellectual formation that can edify people’s faith to become as Vatican II aspired – fully conscious and active participants. The cultural situation demands equipping ourselves with confident apologetics to defend the hope within as St Peter instructs in the scriptures.

Apologetics

So, what exactly is ‘apologetics’ and how should we engage with it? Although the word sounds like it’s related to ‘apologise’, apologetics more accurately translates from the Greek apologia as ‘defence’. Defence, or apologia in this sense, has nothing to do with an angry confrontation, but rather a confident witness to a faith that gives you joy.

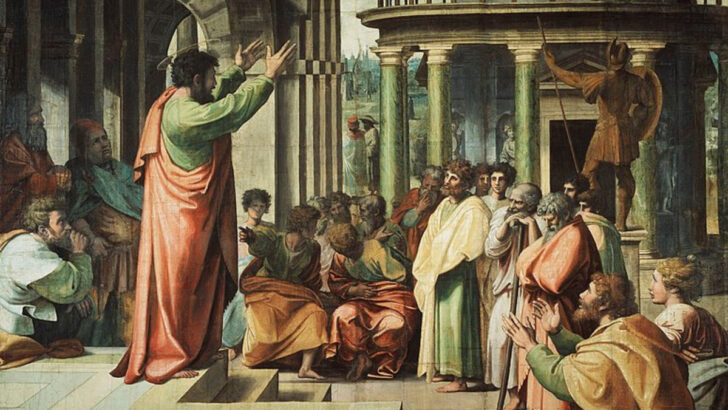

While St Peter gives us the instruction to be ready to make this defence, St Paul offers us a practical template in the Acts of the Apostles.

While on mission in Athens, Paul uses an evangelical technique known as the Semina Verbi, or the Seeds of the Word in which he preaches to the culture in a non-confrontational dialogue. Firstly, Paul is invited by the pagans to defend his faith, which alone demonstrates that we must be compelling enough in our joyful witness to make people want to know more. Secondly, when defending the faith, Paul points to something positive in the culture, and then explains how it points to their desire for God.

How can we use this example in conversations we might have over a coffee or a pint when we’re placed in the hot seat over matters of religion?”

Acknowledging that the pagan culture is very ‘religious’, Paul commends their willingness to accept that there is a mystery behind the universe to which they are unfamiliar with by erecting a statue to an ‘unknown God’. Paul then uses this impulse to point them to the very grounding and source of all things – the one true God revealed through Jesus Christ.

So how can we use this example in conversations we might have over a coffee or a pint when we’re placed in the hot seat over matters of religion?

Study

There are two important elements in St Paul’s example evangelising the pagans that we can apply in our own ‘religious conversations’. Firstly, we need to know what we’re talking about.

While many of the questions people have about the relevance of religion today might seem like new questions, the good news is the Church has been tackling these issues for over 2,000 years and has an abundance of eloquent philosophical, theological and spiritual reasons and resources in its arsenal. It is up to us however to study them.

In the late 19th century, St John Henry Newman sought for an educated laity who did not just know the creed, but could “give an account of it, who know so much of history that they can defend it.” Newman would have longed for an age where sophisticated theological knowledge could be freely available to anyone by the click of a button. In the world of mass media today, it is possible to receive a free education online from so many resources which Newman would have only dreamed of. We just have to make use of them. It is essential to study the faith so we can speak the truth in a tangible manner.

The second essential element to St Paul’s technique in Athens is to know the culture. If we’re going to be effective in our responses, we need to know where people are philosophically. What is going on in the culture? What are people’s underlying perceptions regarding God and the spiritual life? Once we know where people are in this sense, only then we can offer something meaningful to them.

In next week’s column, we will therefore take a philosophical look at today’s culture and asses the most common assumptions regarding faith in contemporary Ireland.

St Paul Preaching at Athens, Raphael (1483–1520)

St Paul Preaching at Athens, Raphael (1483–1520)