A History of Irish Magic,

by Sally North and James North

(Holythorn Press, limited hardbound edition € 60.00; paperback edition, €30.)

When the remains of the poet W. B. Yeats were brought back to Ireland in September 1948, they were interred as he had intended in Drumcliffe Churchyard in Sligo, according to the ritual of the Church of Ireland.

Yeats by culture might have been a Protestant, but having been a life-long pagan in his own mind, he was most certainly a keen devotee of esoteric beliefs of many kinds. This thinking often flavours his poetry.

Here, however, we must be clear about the difference between “creed” and “cult”. A creed is a faith open to all largely by adherence or by a simple rite of adhesion. But a cult is something exclusive, it is for the elected few, the chosen ones of special insight, often with undisclosed secret doctrines.

Important

Yeats’ mystical ideas are important, and for many of those concerned with his work at any level, anything that throws light on what he actually believed would be very important. This new book contains a great deal about Yeats, one way or the other, but alas after all the detailed research of people like George Mills Harper and Ellic Howe, not to mention R. F. Foster, it says nothing novel about his beliefs.

The authors describe their book as “A unique exploration into Irish druidism, fairy lore, miracle-working saints, sacred kingship, witchcraft trials, the Celtic Order of W. B. Yeats, the Theosophical circle of “AE”, and mystical artist Art O’Murnaghan, A History of Irish Magic is the first book of its kind – deeply researched yet highly readable.”

Their themes are important ones for any student of religion, folklore and literature, but they have to be approached with caution. Take those ‘renowned druids’ for instance’”

If that seems to cover a great deal of ground, it is dismaying to find that the authors, products of Oxford University and the Warburg Institute in London, provide no references and no bibliography. Reading an undocumented book of this kind leads nowhere as the authors do not provide the reader with the means to explore further, to grow beyond this text, or even to challenge the truth of what the authors have written.

Their themes are important ones for any student of religion, folklore and literature, but they have to be approached with caution. Take those “renowned druids” for instance.

What we know about the druids and what is written about them today derives almost entirely from the remarks of Julius Caesar in his Gallic Wars (the De Bello Gallico of our schooldays), circulated from 58 BC onwards while the war was being fought. This is a biased account, in which the gods of the Gauls are identified with those of the Roman pantheon (itself derived from the Greeks, the Romans not being a naturally religious race).

Speculation

Nearly everything that is written about the druids outside of this is speculation, wishful thinking, often pure invention. The substance of what we can know has been carefully expounded by T. D. Kendrick, Stuart Piggott and a few others. But what we see in Wales and Scotland and now in Ireland involving white robed initiates at midsummer is the creation of the last few centuries. It does not come down from the ancient past.

Readers of this book will have to be careful in accepting much of what they are told in these pages. But the true focus of the authors is not on anthropology and archaeology, but on the various mystical, often semi-Masonic, cults that have emerged since the 17th century.

Here perhaps they are on more certain ground, but readers will have to be careful of what cultists say about themselves. Take the Dublin Theosophists. A central figure in this group was the poet, painter, social activist, editor and true patriot George Russell, rightly regarded by many as a man of almost saintly character.

For an aspiring student of the esoteric in Ireland it will make an entertaining start, if read with great caution and many a suspecting glance”

He was exceptional. The reputation of Theosophy in the wider community was a little more charged a century ago. We can recall that the school teacher Mr Bentham “from Rathmines”, in Juno and the Paycock, is the theosophist responsible for writing the will that impoverishes the family and who seduces and abandons young Mary Boyle. He is seen by the socialist Sean O’Casey as a foppish, posturing rogue, too clever by half, who flees responsibility. No genial kindness, no secret wisdom, there.

In a short review I have hardly room to discuss in detail all that is included in this briskly written book. For an aspiring student of the esoteric in Ireland it will make an entertaining start, if read with great caution and many a suspecting glance; and, of course, the realisation that much of what it says will have to be unlearned.

Peter Costello

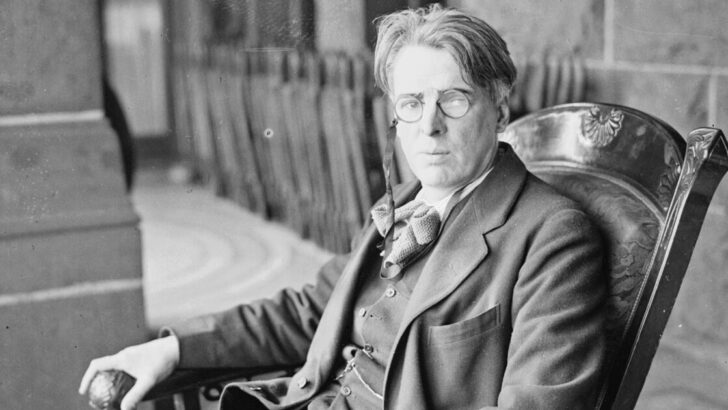

Peter Costello Poet W. B. Yeats, the great magician in a more relaxed moment in the 1920s

Poet W. B. Yeats, the great magician in a more relaxed moment in the 1920s