“The heritage of ancient Holy Ireland has been woefully underdeveloped in recent years – almost ignored”, writes Mary Kenny

One of the leading items on my ‘bucket list’ (things to do before you die) would be to walk the Camino of St James in Spain – or at least to walk some of it. It must be a great achievement to have travelled, on foot, the 800 kilometres across Spain to Santiago. Or to have done the 610km starting from Lisbon or the 227km from Porto.

But such mileage may be a little too daunting for me now. So it strikes me as a terrific idea of John O’Dwyer’s – of Ireland’s National Pilgrim Paths – to campaign for an Irish version of the Camino, stretching a mere 120km.

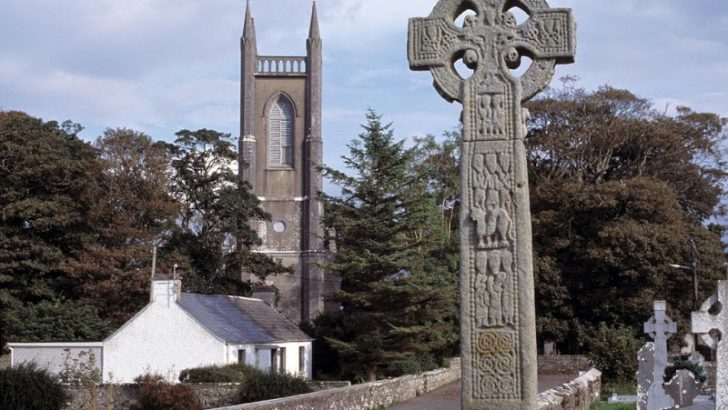

The Irish Pilgrim Path could start from Glencolmcille and Lough Derg in the North, moving across the country to Slí Mór and Clonmacnoise. Properly publicised, it could attract as many visitors as the highly successful Wild Atlantic Way.

The heritage of ancient Holy Ireland has been woefully underdeveloped in recent years – almost ignored.

A woman I know who travelled the Camino (from Canterbury) on horseback tried, similarly, to make her way to the holy places of monastic Ireland on her faithful steed, but found the terrain impassable – roads and motorways were unfriendly to horse and walker alike.

As Mr O’Dwyer has said, there is great potential for a pilgrims’ way walk in Ireland, and it already attracts interest from overseas: as with the Camino, not everyone who follows a pilgrimage trail does so for purposes of devotion – some just want to get away from the raucousness of the modern world, and to contemplate nature and the great mysteries of life.

Our leaders have been so keen to promote secular Ireland that they may have overlooked the historic deposit of Holy Ireland: it has taken the makers of Star Wars to awaken more of us to the wonders, sacred and natural, of Skellig Michael.

Obscurity

The Camino in Spain has developed dramatically in recent decades. It was an ancient pilgrimage, but in modern times, it had fallen into obscurity. In the 1980s, only a handful of pilgrims walked it annually. Now, each year, more than 250,000 people walk, bicycle or ride on horseback (even on donkeyback) some substantial part of the Camino of St James.

Ireland can develop its own version, and those of us who baulk at 800km in the sun may feel equal to 120km in a more temperate clime.

Celebrating ‘The Bard’

The 400th anniversary of the death of William Shakespeare, aged 52, is marked on April 23, and Shakespeare lovers globally will be celebrating the life and works of the Bard.

A friend of mine in Rome, Tony Duff, is holding a Shakespeare soiree, with recitations and discourses from his works, which I think is a lovely idea.

For the event, I think I’ll just revisit favourite Sonnets, which include the lyrical Number 18 (“Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?”), the comical 130 (“My mistress’s eyes are nothing like the sun”) and the many which are so reflective of all passing things.

I can never look at the waves lapping upon the seashore without thinking of Sonnet 60: “Like as the waves make towards the pebbl’d shore/So do our minutes hasten to their end;/ Each changing place with that which goes before/In sequent toil all forwards do contend.”

Correct name for natives of Lesbos

Should people from Lesbos be correctly called ‘Lesbians’? Our parish priest in Kent faltered over this point of nomenclature, speaking from the altar last week. It was evident he didn’t want to risk sniggering in the pews, so he raised the question tentatively and then left it there.

Perhaps some Greek scholar could settle the point.

Debate over Shakespeare’s faith

Whether Shakespeare was a Catholic or not is still debated, although Clare Asquith makes a strong case for the Bard’s faith in her compelling biography Shadowplay: The Hidden Beliefs and Coded Politics of William Shakespeare, available in paperback. Lady Asquith vividly illuminates the difficulties Catholics were under in Tudor England, especially acute in the 1580s, when Shakespeare’s career began to take off.

It could be quite dangerous to affirm the Catholic faith at this time and Will would have had to keep his religious beliefs carefully hidden if he was to continue to function – or even to survive – as a writer under Elizabeth’s patronage.

There is a gap of seven years in Shakespeare’s life which no scholar or biographer has been able to account for: he disappears from the historical radar, and then re-surfaces again. It’s suggested that he may have been a tutor to a recusant Catholic family in the north of England during this time. He might also have been in Italy, since Italy appears quite often in his work. We must now hope he’s in Heaven while we cherish his beautiful words on Earth.

Mary Kenny

Mary Kenny