The Tilson Case: Church and State in 1950s Ireland, by David Jameson (Cork University Press, €39.00/£33.99)

The Tilson Case hit the Irish public in the Holy Year of 1950. The West was over-charged with feeling, almost hysterical. In Hungary Cardinal Mindszenty had been imprisoned. The Korean War was in full swing, with the potential for nuclear exchanges. A godless communism was sensed to be rampant and almost unstoppable.

In Ireland, these ominous events were to be countered by an outpouring of popular Catholic devotion, such as the Pax Christi Crusade of Prayer, special devotions to the Immaculate Heart of Mary and Our Lady of Fatima – and always the ubiquitous rosary crusades. A popular groundswell led the Pope to declare the Assumption of the Virgin Mary as a dogma of the faith in November of that year. Into this maelstrom of feeling and anxiety in Ireland intruded the Tilson case.

Facts

The facts seem clear enough. In 1941 Ernest Tilson, a Protestant Dublin Corporation worker, married Mary Barnes, a Catholic. They went on to have four children.

“The union has not been altogether happy,” as Mr Justice Gavan Duffy (a name for many with patriotic overtones) understated it in the High Court. In April 1950 Tilson deposited three of the children in a Protestant children’s home, claiming that under Catholic canon law and Ne Temere he had been forced to agree that they be raised as Catholics.

But it cannot be ignored that previously Mr Tilson had been summonsed for neglecting his family. He had to make over a substantial proportion of his salary in support payments; the Supreme Court would later suggest that placing the children in the home was “an ingenious” way of improving his financial position.

Mrs Tilson, supported by Catholic interests, sought their return and the High Court gave judgement in her favour. The President of the Court, Judge Gavan Duffy, appeared to ground his ruling on the 1937 constitution’s ‘special position’ of the Roman Catholic Church and it was interpreted as enshrining Ne Temere in Irish law.

The case went to appeal. The original judgement was upheld, but the Supreme Court in its turn subtly changed its basis into one founded on contract law, in which the Tilsons had agreed to bring up the children as Catholics. Neither party could unilaterally abrogate that contract.

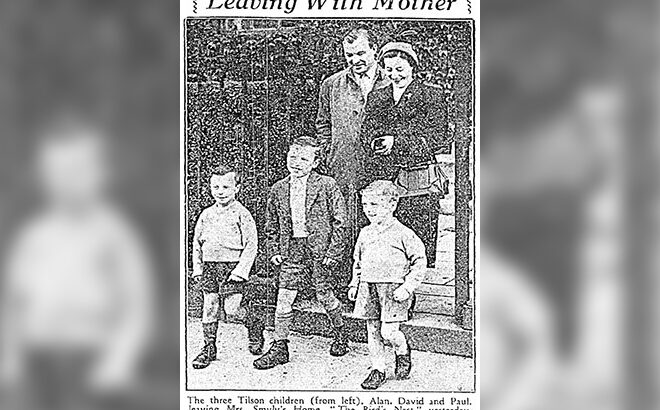

This established the principle that parents “have a joint power and duty in respect of the religious education of their children” and the legal equality of the sexes in guardianship matters. The three children were released back into the care of their mother, and she quickly reclaimed them.

The Tilson case has attracted attention from three angles. The first was a jurisprudential one, in which important principles of the law relating to contract, the place of Common Law after the 1937 constitution, and how the ‘special position’ of the Catholic Church under that constitution might be interpreted, as well as the motivations and views of the judges that dealt with the case in the High and Supreme Courts.

A second angle was political, how the parties in the case – Mr and Mrs Tilson – may have found themselves as part of a proxy war between a defensive Protestantism and a Catholicism at arguably its most powerful and influential over the political and public realm in post-independence Ireland.

A third angle is the most poignant and concerns the human story – the relationships and often traumatic domestic dramas behind the legalese, the bewigged barristers and the shadowy manipulators.

Forensic

David Jameson’s book – well-rounded and forensic — will be required reading for those wanting to interpret and understand mid-century independent Ireland.

He shows how powerful Protestant and Catholic interests used the hapless and confused Tilsons to argue what values should govern post-1937 constitution Ireland – and that the grey eminence of Archbishop McQuaid was never far away.

Jameson is critical of the overt and covert Catholicism in the legal judgements and how it influenced the judges’ attitudes, especially those of Mr Justice Gavan Duffy in the initial hearing – though that has not been without its Catholic critics, such as Donal Barrington and Finola Kennedy. In that regard, northern unionists who interpreted the case as embedding the Catholic Church’s canon law in Irish jurisprudence may have had a point at that time.

But at the end of it all it is good to know that in later years the Tilson family got back together again. Their private life eventually survived its traumatic excursion into the public arena. The Tilson case was largely the product of a particular point in time. It highlighted the denominational disputes that were not uncommon in 1950s Ireland. In an ecumenical age we have thankfully moved on. Families have other preoccupations these days.

After her trials: Mrs Tilson is pictured with her three children.

After her trials: Mrs Tilson is pictured with her three children.