Ulysses: a reader’s odyssey by Daniel Mulhall (New Island Books, €15.95)

This book is a delightful, chatty introduction to the wonderful world of James Joyce’s Ulysses.

It is written by Daniel Mulhall, an Irish diplomat for more than 40 years and now Ireland’s ambassador to the United States of America. In the prologue to his book, he muses on the importance for Ireland of what he calls “cultural diplomacy” – in other words, using “the lure of our literature as a resource for creating vital affinities with Ireland”.

He writes that our great writers give us a profile overseas that we could not otherwise achieve.

The book had its origins in blogs that Mulhall began posting on the Washington embassy’s website in 2018, with the aim of “elucidating Joyce’s great novel for American audiences”. Its aim is to do the same now for a wider audience.

It makes no claim to be an academic study, though Mulhall has read deeply in Joycean scholarship and has immersed himself in Joyce’s writings. He is addressing a general reader, the ordinary man and woman – an appropriate audience since the principal character in Ulysses, Leopold Bloom, is “an exceptional figure because of his essential ordinariness” (to quote Mulhall).

Mulhall commends Ulysses to us on the basis that “Bloom is ultimately a life-affirming character, and Ulysses a life-affirming novel”. He admits that “reading Ulysses is a daunting undertaking… with its frequent shifts of writing style and the mix of narrative, dialogue and interior monologue”, but his helpful advice to “readers who encounter passages they struggle to understand is not to be deterred, but to move on”.

He even suggests that readers who do not have the stamina to read the entire work should read just seven of its 18 episodes, the “more accessible and immediately compelling” ones z– namely, 1 (Telemachus), 2 (Nestor), 4 (Calypso), 6 (Hades), 8 (Lestrygonians), 12 (Cyclops) and 18 (Penelope) – in order to get “a flavour of what it [the complete novel] has to offer and of the feat of writing that it represents”.

Focus

A central focus in Mulhall’s book is what can be gleaned from Ulysses about our history. Mulhall tells us that he has “come to Joyce through a passion for Irish history”. While we must be cautious about reading Ulysses as history, it is nevertheless deeply rooted in actuality and suffused with a sense of history: it is, to quote Elizabeth Bowen about her novel The Last September, “fiction with the texture of history”. That is part of its charm for Mulhall – and indeed for this reviewer.

Its action, such as it is, famously takes place on June 16, 1904. It thus captures Dublin on the cusp of change, figuratively in transition from Parnell to Pearse. Parnell was Joyce’s great hero, and Mulhall notes that Joyce attended an Irish language class conducted by Pearse but soon dropped out because “he objected to Pearse’s habit of denigrating the English language”. He speculates that “Joyce’s political outlook lies somewhere between the assertive parliamentarianism of Parnell and the more advanced but non-violent nationalism of Arthur Griffith”.

In Ulysses, Bloom opines that “revolution must come on the due instalments plan” – that is to say, gradually – and Stephen Dedalus dismisses patriotic zeal with its concomitant violence by exclaiming: “Let my country die for me… Damn death. Long live life.” There is no doubt these sentiments are those of Joyce himself.

Anyone planning to mark the centenary of the publication of Ulysses this year by dipping into Joyce’s masterpiece would do well to begin by reading Daniel Mulhall’s book.

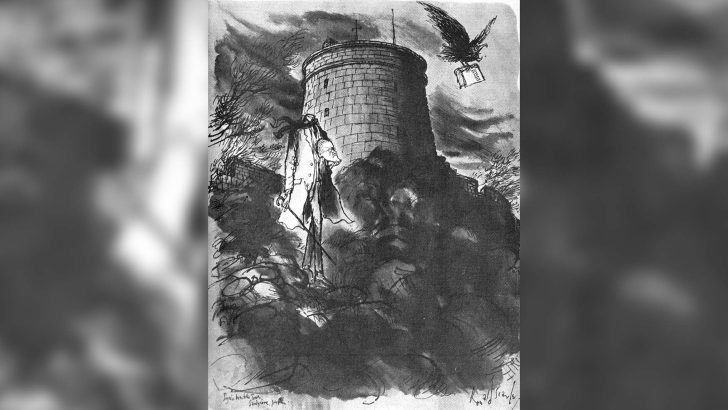

“The ghost of Sandycove Tower”: James Joyce, as

reimagined by Ronald Searle (drawing in ink and wash, 1963).

“The ghost of Sandycove Tower”: James Joyce, as

reimagined by Ronald Searle (drawing in ink and wash, 1963).