A Life in Medicine, from Asclepius to Beckett

by Eoin O’Brien, foreword by John Banville (Lilliput Press, €25.00 / £21.00)

Irish literature is filled with examples of leading medical men, who were also creative and bold litterateurs. One thinks of Sir William Wilde, Oliver St John Gogarty, J. B. Lyons and many others.

As a medical man the author is a specialist in cardiology, so one might almost say that for most of his life the Irish heart and its dramas, as reflected in clinical research, literature and painting, have been close to his own inner self.

He is already the author and editor of some nineteen books, so this makes the 20th. It provides the background in which those other books were written, which tell us not only about writers and painters, but also the more shadowy world of medicine in Dublin, which he has done too much to improve, amending and enhancing the lives of so many people. I suspect without the medical experiences he would not be the biographer that he is.

He has cast his own account of his life into three parts. The first deals with his own origins and early years; the second with the world of medicine which has been (quite literally) at the heart of his own life; and part three with encounters in literary Dublin especially with such talents as Con Leventhal, Neville Johnson, and Niall Sheridan.

These are not name bandied about much by the canonists who rule the highlands of Irish writing, but all three were men of mark, of exceptional and varied talents, and insights that would otherwise be lost.

But, of course, the crown of his life was his encounters with Samuel Becket, and the experiences that went into the creation of what is perhaps his most widely read book The Beckett Country: Samuel Beckett’s Ireland, a book which he created from inception to design himself. It is a book which one still takes down and reads a little of for the sheer excellence of it visually and verbally.

But as the design of the present books suggests, through those difficult; early years, to his own achievements, medicine is at the heart of it all. Interesting and revealing.

Indeed I got great amusement out of the account of his childhood for various reasons, the least of which is sympathy with his troubles about his Tables and learning the alphabet. This is filled with a glimpse of Dublin 4 in the old days: Miss Meredith’s, St Conleth’s, and even St Bartholomew’s.

(Though like most Conleth’s boys he was unaware of the glorious trove of Jack Yeats paintings which filled Mr Sheppard’s own quarters.)

This heredity and these years were the making of the man. He was not so happy at Castleknock. These Catholic years he sums up succinctly; he feels that to inculcate the developing mind with doctrine and dogmas can only cause detriment to maturation and expression, “that such manipulation of susceptible immaturity can lead to attitudes and actions that are detrimental to the individuals and society.”

This was true then, but the recognition of the need for a sense of true Christian maturity at the time of Vatican II led to a more open minded situation.

This book is all the better for its austere and dryly amused.

Peter Costello

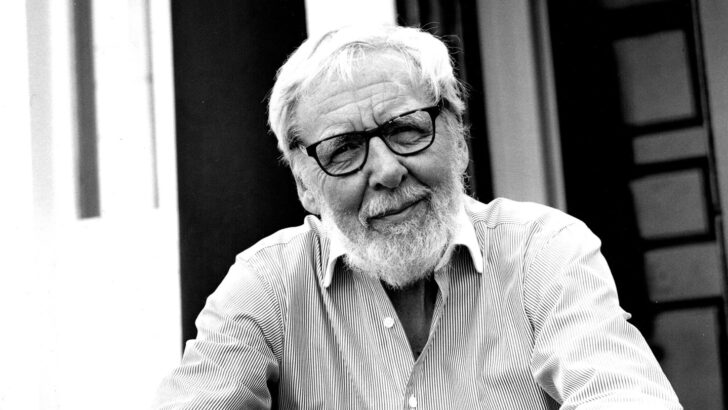

Peter Costello Dr Eoin O’Brien, taking stock of the past

Dr Eoin O’Brien, taking stock of the past