Cardinal Newman – Special Supplement

Newman’s canonisation will allow the Church to shine a spotlight on his teaching, Greg Daly is told

God, as they say, moves in mysterious ways, and the path that led Fr Ian Ker to become the world’s leading Newman scholar seems to have apparently random divine footprints all over it.

“It’s all because the wife of a colleague left him,” he says, explaining how he had been teaching at the University of York at the time, invited the colleague for dinner when they were both in London, and there been joined by an Italian academic who he eventually ended up driving to Oxford.

On the way there the Italian explained that he was working on a selection of Newman’s works in Italian, and asked his English driver to do the notes on them.

“Well, only one volume ever came out but he suggested that I do them as an Oxford critical edition, and that was the beginning of the whole thing,” Fr Ker says. “Otherwise I’d never have done it – I wouldn’t be a priest either, probably!”

Sages

The reason the subject had come up, Fr Ker explains, as that he had been doing research on Victorian ‘sages’, people like Thomas Carlyle, and it struck him that Newman was much more intelligent than the others.

“My interest was primarily literary to begin with. When I had done this edition it occurred to me that there was a need for an intellectual and literary biography of Newman, because there really wasn’t one,” he says, with the upshot being the massively acclaimed 1988’s John Henry Newman: A Biography.

“The book was a great success, so that’s really what put me on the map,” Fr Ker says, explaining that Newman’s enduring fascination has a lot to do with his remarkable range as a writer.

“He wrote classic works in Theology – The Development of Christian Doctrine, in the philosophy of religion – The Grammar of Assent, in literature – the Apologia Pro Vita Sua, in education – The Idea of a University is still sort of a standard book that everyone refers to, and he wrote for Catholics on spirituality, and for Anglicans too,” he says. “He had a very big field and wasn’t just a theologian by any means.”

****

Newman’s path in life was, of course, anything but straightforward, and sometimes offers salutary lessons for today’s Catholics. It seems fitting that today’s Catholic Voices movement, launched ahead of 2010’s beatification of Newman, takes as a principle that crises offer opportunities to tell the truth of what the Church really teaches, given how Newman’s own spiritual biography, the Apologia Pro Vita Sua was a response to criticisms by the Anglican priest-author Charles Kingsley who accused Newman of dishonesty.

“Newman was hugely grateful to Kingsley, because he enabled him to defend himself, and he said Mass for Kingsley when he died,” Fr Ker says. “He was very, very grateful to Kingsley, because he’d been under attack for so many years, but this gave him the perfect opportunity to reply and tell the story of how he had grown in his understanding of Christian Faith.

“It was a very Protestant country at the time,” he continues. “There’s a wonderful story of him sitting on a train at Paddington Station to go to Oxford, and he hears in the next compartment – the wall must have been rather thin – somebody saying ‘depend upon it, sir – Newman is a Jesuit’. He was quite serious, and was probably an Oxford don, so the Apologia was designed to show that he exemplified precisely his theory of development of Christian doctrine. He hadn’t abandoned his faith, but had moved through various stages and finally become a Catholic.”

This notion that something can change while remaining true to itself was a key idea of Newman’s, and something that has had a tremendous impact since, Fr Ker explains.

“It’s the thing (Pope) Benedict was often talking about, about change in continuity rather than change in rupture,” he says. “Newman began as a Bible Protestant, then he had this Evangelical conversion, then he drifted directly – dangerously as he put it in the Apologia – in the direction of liberalism when he was elected to Oriel College.”

There he pioneered what’s now known as the Oxford tutorial system, where students met with individual tutors on a one-on-one basis, Fr Ker says, rather than in classes of 15 or so students.

“If you wanted any private help you had to hire a graduate student, as Newman himself had done, and he thought that people shouldn’t have to pay for private tuition but that tutoring should be done by the tutors,” he says. “So he introduced a system with another three tutors. The provost thought it was a cult of personality, and so he was sacked.”

****

Without a teaching career, Newman became a fulltime research fellow, Fr Ker says, with this transforming him.

“That’s when he really began systematically to read the Fathers,” he says. “He used to say that it was Oxford made him Catholic, meaning that it was there he read the Fathers and it was the Fathers who brought him into the Catholic Church.”

This didn’t happen overnight, of course, as Newman would first play a leading role in the Church of England’s so-called Oxford Movement, which began in 1833 with concerns about State intervention in Church affairs and tried to grapple with the nature of the Church.

“Originally there was a meeting up in Hadleigh in Suffolk, and the original people who wanted to protest against the government’s intervention wanted to set up a committee,” Fr Ker says. “In his Apologia, of course, Newman said living movements do not come of committees. He was completely against the idea of a clerical committee and he began then the Tracts for the Times. It was rather like a modern ecclesial movement in the Catholic Church because it included both laypeople and clergy.”

Through the Tracts, a series of 90 publications, many of which he wrote, Newman became a household name.

“He was effectively the leader of the Oxford movement, through the tracts and through his preaching at St Mary’s which was famous – people used to say ‘Credo in Newmanum’, and of course they changed the hour of dinner in the colleges to try and stop students from going to St Mary’s to hear Newman.”

In 1839, however, when researching the 5th-Century Church, the then Anglican clergyman had what Fr Ker describes as “a terrible shock”.

“He was studying the Monophysite heresy, which of course he knew all about already, when all of a sudden something struck him. He said ‘I saw my face in the mirror, and I had a Monophysite face’,” Fr Ker says. “He suddenly saw that the Monophysites had broken into two parties, the semi-Monophysites and extreme Monophysites, and Rome was on the other side.

“So this gave him a horrible shock, because this via media of which he was the theological architect, between Rome and Geneva, looked uncannily to him like the Monophysites, because you had the Protestants on the one hand who were the extreme Monophysites, and Rome on the other, and the Anglicans in the Middle,” he says, adding: “That was really what began it.”

****

A second shock came when he realised how St Augustine had ultimately rejected claims by the North African Donatists on the basis of Rome’s authority. “Augustine made the point that it’s no good the Donatists making theological arguments for their position because Rome has decided and that is the end of it,” he says.

Yet another shock followed when his famous Tract 90, arguing for a Catholic interpretation of the Church of England’s 39 Articles – he said they criticised not Catholic doctrine but medieval errors and corruptions – was roundly condemned by university and episcopal authorities.

What Newman wanted to do…was to combine the collegiate tutorial system of Oxford with the continental university system of lectures at, let’s say, Louvain”

“He was arguing that the bishops were the successors of the apostles, but these bishops were condemning him,” Fr Ker says.

“He became convinced that the modern Roman Catholic Church, however unlikely it might seem to the early Church, nevertheless was like looking at the photograph of a man in his 40s and then looking at the photograph of a boy aged 10 or 11 or whatever,” he continues. “You can see they’re the same person – much changed but still the same person. He thought that a living idea had to develop, and that there was only one church that had a mechanism for authenticating development, and there was only one church that actually did develop doctrine.”

Seemingly faced with the inevitability of Rome’s claims, he worked over the following few years on his Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, and on October 9, 1845 was received into the Catholic Church by a Passionist priest, Blessed Dominic Barberi, whose principal mission in England was to the poor of the industrial midlands.

Community

Ordained to the Catholic priesthood himself in 1847, Fr Newman joined St Philip Neri’s Congregation of the Oratory, and established an Oratorian community in Birmingham, a few years later being invited to Ireland to help found a Catholic university – the ultimate ancestor of today’s University College Dublin.

“When the opportunity came to found a Catholic university in Ireland, he jumped at it,” Fr Ker says. “It was a chance to found a Catholic university which he hoped would be a Catholic university for the English-speaking world. Irish Americans were very interested and would have been glad to go to Dublin. But when he went there he was advised by everyone that it really wasn’t viable.”

A key part of the problem, Fr Ker explains, is that the nascent university couldn’t grant degrees, with the Government of the day refusing to give the determinedly Catholic institution a charter to do so.

“And then of course he also had a lot of trouble from Archbishop Cullen,” Fr Ker continues. “It’s amazing to us today when under canon law every parish has to have a finance committee, but when he tried to set up a lay finance committee, Cullen absolutely forbade it. The Church was so clerical. And Newman couldn’t raise money for the university without a lay finance committee, with lay people involved in trying to get money.”

****

Newman’s frustrated aim, Fr Ker says, was to blend the best features of the best of British and continental university education.

“What Newman wanted to do, and I think I’m the first person to point this out, was to combine the collegiate tutorial system of Oxford with the continental university system of lectures at, let’s say, Louvain. Because what he thought was wrong with Oxford was that the professorial element was very weak, and thought that it was important that the professors should give lectures, which they often didn’t bother to do in Oxford in those days.

“The colleges were much, much stronger than the university, and in Dublin he wanted the professors to run the university, not the heads of colleges. He reproduced the colleges in these hostels which were led by young priests,” he continues.

All of this makes it all the stranger that at the time of writing neither UCD nor the Irish Government is planning on sending anybody from Dublin to attend Newman’s canonisation, but this invites the obvious question of why Newman’s canonisation matters. As a ‘Blessed’ since 2010, he is already recognised, after all, as a saint in Heaven, enjoying the Beatific Vision.

“I think the important thing is that enables Newman to be declared a Doctor of the Church, because you can’t be one without being a canonised saint,” Fr Ker says. “I regard him as a Doctor of the Church for the post-conciliar period, and I’ve argued this in my last book, Newman on Vatican II. I think he can be seen as a Doctor of the Church for our period like St Robert Bellarmine was a Doctor of the Church for the Tridentine Period.”

Traces

Traces of Newman’s influence can be spotted in such Council documents as Dignitatis Humanae on religious freedom and Lumen Gentium, the dogmatic constitution on the Church, Fr Ker says, though he concedes that Newman’s influence is only indisputable in one.

“The only specific reference to Newman in the Council documents is in the Constitution on Divine Revelation, where the development of doctrine is referred to,” he says. “That probably was put in by Yves Congar, because Newman anticipated by 100 years in their emphasis on the library of the Fathers what the French would do 100 years later when Danieliou and de Lubac began the Sources Chrétienne, the so-called Ressourcement movement from Scriptures and the Fathers.

“And without that theology,” he says, “Vatican II couldn’t possibly have taken place.”

Greg Daly

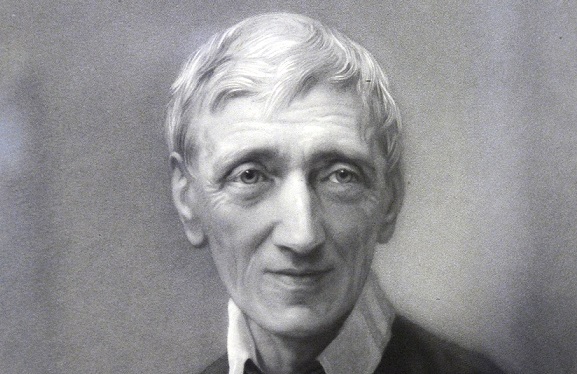

Greg Daly Blessed John Henry Newman

Photo: CNS

Blessed John Henry Newman

Photo: CNS