The View

All saints are extraordinary, in the sense that they manage to turn their lives and wills over to God and through his grace achieve heroic virtue.

John Henry Newman is perhaps more extraordinary than most because of the extent of his natural gifts. James Joyce wrote to his long-suffering English patron, Harriet Weaver, that “nobody has ever written English prose that can be compared with that of a tiresome footling little English parson who afterwards became a prince of the only true Church”.

Joyce was profoundly influenced by Newman but so was Sophie Scholl, one of the members of the White Rose movement who peacefully opposed Hitler. So, too, was Mohandas Gandhi, the great Hindu leader whose favourite hymn was ‘Lead, Kindly Light’. The list goes on, from Thomas Merton to Pope Emeritus Benedict.

An exquisite prose stylist, a man of courage, a theologian, a philosopher – the depth and degree of Newman’s gifts are indeed extraordinary.

And yet, I have a very soft spot for Newman the pastor, the father of souls. It is hard to tell when that aspect of him begins but it was definitely present when he proposed a tutorial system in Oxford, where every student would have access to an elder brother figure who took a lively interest not just in how the student was progressing academically, but as a human being.

(Or more accurately, as a man. Newman does not seem to have conceived of university education for women, despite deep and harmonious relationships with women that on occasion, lasted for most of his life. Maria Giberne is one such example. He knew her since they were both young and he had a portrait of St Francis de Sales in his private chapel that was painted by her. Like Newman, Giberne converted to the Catholic faith; she became a Visitation Sister in France.)

Many of the Catholics he served were poor, Irish immigrants fleeing the dreadful conditions in Ireland”

The tutorial system was the precursor of the famous Oxford tutorial system, where students have a tutorial group for every subject consisting of only one or two other students. Sadly, today, the focus is often purely academic.

While still at Oriel College in Oxford and an Anglican minister, Newman was appointed to St Mary’s parish. Littlemore was a straggling hamlet on the outskirts of the parish. The people of Littlemore were poor. He took his duties very seriously, far more seriously than previous incumbents. He moved his mother and sisters into the parish and persuaded them to set up a rudimentary school after he conducted a census and discovered that most of the children were illiterate.

He persuaded Oriel College to help him build a church and afterwards, a small school. He played the violin for the children and used it to help him teach them hymns.

Conversion

After he was compelled to leave Oxford because one of the tracts he wrote on the Anglican 39 Articles was considered scandalous, he set up a semi-monastic community in Littlemore in an old stable that had once belonged to a coaching company. It was there he eventually converted to Catholicism.

When Newman moved to Birmingham, many of the Catholics he served were poor, Irish immigrants fleeing the dreadful conditions in Ireland. In a Mass for Newman’s canonisation celebrated by Cardinal Nichols, Archbishop of Westminster, Father Ignatius Harrison, Provost of the Birmingham Oratory, described how Newman’s love for the poor developed even further.

Fr Harrison described that Newman was not just canonised for his skills as a theologian and a philosopher, but for his “compassionate heart …taking bags of coal to poor factory workers who were freezing to death; the same priest who regularly made private gifts of £5 to those in need; the same priest who consistently made efforts to help the unemployed in Birmingham find decent work, especially women; the same priest who went at his own risk to help cholera victims in other parishes”.

He sat in a cold, insect-infested confessional for hours, hearing confessions”

St Philip Neri, the founder of the Oratorians, was also famous for his concern for the sick and poor. Newman was profoundly influenced by his example. Fr Harrison tells us that Newman lived in conditions of poverty himself and did not take holidays for the simple reason that he could not afford them.

He sat in a cold, insect-infested confessional for hours, hearing confessions and giving spiritual direction to among others, poor factory girls. He visited prisoners and his Oratorians visited hospitals.

Newman’s love for the poor was not sentimental and neither did he romanticise poverty, doing his best to help people evade its clutches, whether it be through education or helping them procure work.

For Newman, cor ad cor loquitur was not just about personal sympathy and friendship with equals, although he could also be described as a patron saint of friendship. Care for the poor whom the world neglected and speaking to their hearts with practical help was also central in his life.

Breda O'Brien

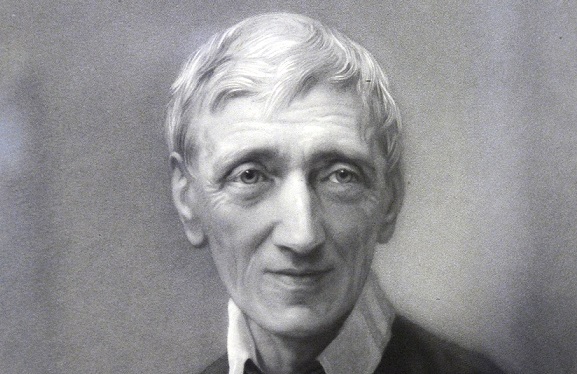

Breda O'Brien Blessed John Henry Newman

Photo: CNS

Blessed John Henry Newman

Photo: CNS