“Influencers” seem to play an important role in our world, although many of us know little about some of these influential individuals, who, via social media, have such sway over the lives of others.

But there are also “influencers” who have a quieter, yet profound and consistent, following, more through a network of personal admirers than through modern media.

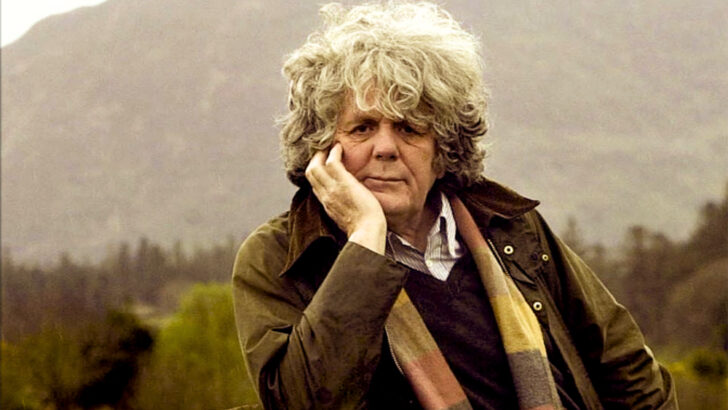

Moriarty

One such, I discovered this year, is the Kerry-born philosopher and writer John Moriarty. He was born in Moyvane, North Kerry in 1938, and died in June 2007, leaving a dozen acclaimed books on themes both spiritual and philosophical (as well as a number of audio recordings.)

In my ignorance I hadn’t known anything of John Moriarty until a collection of his writings “Grounded in Story”, published by the respected Lilliput Press this year, was given to me by a friend some months ago.

What’s special about Moriarty is the way he evokes an Ireland that is now gone, and its relationship both to the spiritual and the hard realities of land and labour. Awe and wonder was partnered with the earthiness of that rural life. “Cutting turf every year in the bog, we worked our way down into a world no human being had ever set foot in,” he recalled. They would reach a floor of pine forest from a prehistoric past.

How privileged we were, believing in something so ontologically superior to us that we yearned to praise it, to bless it, to adore it, to glorify it”

“Ours was a bleak parish, mostly,” he wrote, “of bad land and bogs, but parish it was, meaning that at the heart of the village…was the parish church.” The rituals of faith enacted in that parish church “gave us the chief sense of ourselves.”

The hardships and sometimes harshness of everyday agricultural life were in contast to the beauty and uplift of the religious rituals he remembered. Killing a pig was a necessary, yet horrible, task that had to be undertaken for the sustenance of life; people had to be grounded in very basic toil, involving blood and mire, soil and mud. Yet, he wrote, they felt privileged to have something better in their lives: “How privileged we were, believing in something so ontologically superior to us that we yearned to praise it, to bless it, to adore it, to glorify it.” Religious rituals, Mass and the sacraments, “enshrined that praise and provided meaning”.

Immortality

These rural smallholders of poor land and wet bogs nevertheless read by the light of the paraffin lamp: young John read from the Greek classics, he read the Odyssey, the Aenid, Moby Dick and Darwin’s Origin of Species. People knew about Ptolemy and Plotinus, as well as the lore of the heron and brown trout and lapwing.

John Moriarty – who studied philosophy at UCD, and spent years in Canada teaching English literature – chose to return to the west of Ireland”

When someone died, he recalled, the people would say “Tá sé, tá sí, imithe ar shlí na fírinne – he or she has set out on the path of truth.” This was “the adventure of our immortality”.

John Moriarty – who studied philosophy at UCD, and spent years in Canada teaching English literature – chose to return to the west of Ireland and live as a gardener in his later years.

The book of his writings is edited by Amanda Carmody and Mary McGillicuddy, and beautifully illustrated. And he is, I believe, a true “influencer”.

The hardships and sometimes harshness of everyday agricultural life were in contast to the beauty and uplift of the religious rituals he remembered”

**

The re-opening of Notre Dame was surely one of the events of the year and a universal acknowledgement of France’s Catholic heritage. The chief architect, Philippe de Villeneuve, said he kept his religious practice to himself while working on the project, as he wanted to remain professional and objective, rather than personal. But after the reconstruction was unveiled, he said that “Notre Dame” – that is, Our Lady – had been an inspiration and a guide to all his endeavours.

The occasion helped to bring a new harmony to church-state relations in France, and something similar is needed in Ireland.

But if Ireland were to celebrate its historic Catholic tradition, it occurred to me that it would not be with a Mediaeval cathedral – our cathedrals are essentially Norman – but a Mass Rock in the middle of a boggy wilderness. For that is where the faith was sustained through the hardest of times.

***

It’s my practice to spend St Stephen’s Day working on my tax papers, due to be remitted in January. Not a fun pastime for the Christmas season, but there’s something apt about auditing your life at the end of a calendar year. “Accounts” also means accounting for decisions and choices, and there’s a lot to be learned from the exercise: how money is organised and spent can be a branch of the counsel to “know thyself”.

Queen Victoria once said that to have done one’s duty is a satisfying feeling. And when the taxes are finally remitted, there can be a virtuous glow of having been a dutiful citizen. Or at least the absence of fear that one might be in trouble with the revenue!

Mary Kenny

Mary Kenny Kerry-born philosopher and writer John Moriarty

Kerry-born philosopher and writer John Moriarty