Andrew Carpenter

Jonathan Swift: The Reluctant Rebel

by John Stubbs (Viking, £25)

It is hard to know what to expect from a new biography of Swift so soon after Leo Damrosch’s massive Jonathan Swift: His Life and His World (Yale University Press, £10.99pb) in 2013, especially if the latest book is clearly designed for the same kind of general audience as Damrosch’s.

The facts of Swift’s life were established by Irvin Ehrenpreis in his definitive three-volume biography (1962-83), which has been the foundation of several one-volume works since. Where Ehrenpreis and his followers have questioned the reliability of many of the stories about Swift that have circulated for years, Damrosch investigated them and accepted some of them as likely to be true.

Swift’s biographers, from Ehrenpreis on, have also interwoven assessments of Swift’s works into their books.

So what, I wondered as I picked up John Stubbs’s 740-page Jonathan Swift: The Reluctant Rebel, could a new biography possibly offer that was new.

I found many enjoyable passages in this book – and Stubbs does repeat the livelier stories; the style is entertaining, and though a dedicated Swiftian will take issue with several of Stubbs’s judgements and question the book’s accuracy in places, its imaginative approach does add something new to Swift studies.

Contention

Stubbs’s contention is that, despite being born in Ireland, Swift always thought of himself as an Englishman and would, in normal circumstances, have sided with England in any dispute.

However, after his return from England to Ireland as Dean of St Patrick’s in 1713, Swift experienced the way in which English politicians and authorities consistently mistreated Ireland – the Declaratory Act of 1720, the Wood’s Halfpence controversy of 1724, and so on.

He took up the pen on behalf of Ireland and, in doing so, became the ‘reluctant’ rebel of the title. Stubbs also addresses the questions of Swift’s relationships with Vanessa and with Stella (whom he rather disconcertingly calls by her surname ‘Johnson’) and spends a lot of time filling in the background to Swift’s works.

This is all fair enough, though in areas where there are few facts to go on, Stubbs is thrown back onto words like ‘possibly’, ‘probably’ or phrases such as ‘it is impossible to know…’.

However, this is part of the point of the book – that it sets out to recreate, as vividly as possible, the world which gave rise to Swift’s works.

Stubbs describes, with gusto, what he imagines the furniture, tableware, paintings and people that surrounded Swift to have been like.

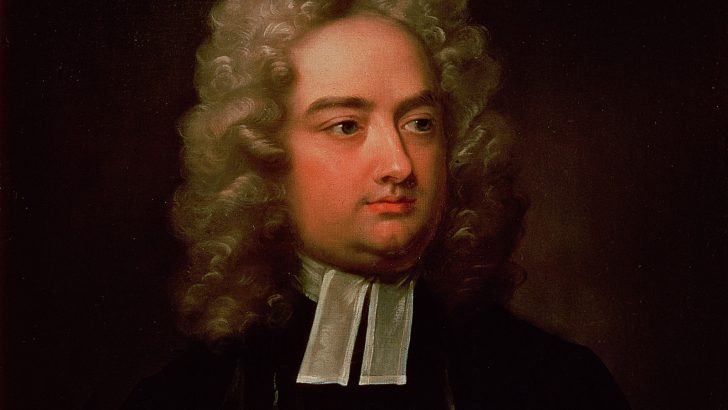

At one point he notes that, in a portrait by Jervas, Swift’s face is that of ‘a man you have seen in a pub, looking up from a newspaper as you brush past his table; and where you might expect a huffy look of annoyance or even hostility, instead you catch a glimpse of unnerving intelligence, humanity and suspended humour.’

Whatever this means, it is more the approach of a creative writer than a sober biographer. This is, in fact, a characteristic of Stubbs’s book – his tendency to insert personal commentary, often highly imaginative. This adds to its entertainment value, but is questionable from a scholarly point of view.

To appreciate Swift’s work, one needs a good understanding of the context in which he was writing. Quite reasonably therefore, a portion of Stubbs’s book is devoted to trying to explain the background to Swift’s political views by investigating his family’s background; but there is so much detail here that the readers may find themselves lost.

Stubbs is a scholar of 17th-Century England, but the reader of this book gets more than is needed on the English background to Swift, and not enough on the Irish background. Stubbs’s chapter ‘Ireland and the Civil Wars’ relies more on English than on Irish sources, and throughout the book there are signs that he has not consulted recent editions of texts from the period, or even significant historians’ books on 17th- or 18th-Century Ireland.

Specifically, any biographer should be aware that many valuable articles on Swift have been published in the six volumes of Proceedings of the Münster Symposium on Jonathan Swift (1985-2013). They have, between them, changed the face of Swift scholarship, but do not figure in Stubbs’s book.

Key work

A key work Stubbs has not consulted is A.C. Elias’s wonderful edition of the memoirs of Laetitia Pilkington, published in 1997– the first biography of Swift – one entire volume of which is devoted to exhaustive notes on Pilkington’s text with information on many of the characters in Swift’s Irish life.

This was made full use of by Damrosch – Stubbs has used Damrosch, but he has not consulted Elias.

Also there are recent editions of the works of Thomas Sheridan and Patrick Delany – as well as good work on Mary Barber, Constantia Grierson, and Swift’s other friends, to which Stubbs makes no reference.

So, enjoyable as this book may be, those who want to keep abreast of Swift scholarship will need to supplement it.

Andrew Carpenter is Emeritus Professor of English UCD.

Jonathan Swift by Charles Jervas

Jonathan Swift by Charles Jervas