The World of Books

By the books editor

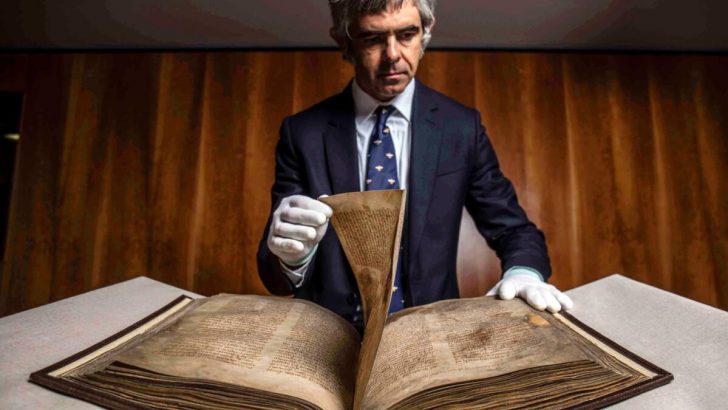

The announcement that Peregrine Cavendish, the 12th Duke of Devonshire, based in England, has presented the celebrated Book of Lismore to University College Cork, comes as a delightful surprise.

In effect, some might say, it give Munster an ancient book to play off against Leinster’s Book of Kells.

The Book of Lismore contains, for instance, a version of what used to be called The Colloquy of the Ancients, the 12th Century AcallamnaSenórach”

The history of the book is wonderfully romantic and now ends on a very happy note. During renovations at Lismore Castle in 1814 the volume was found sealed up in a cavity in a wall. It had been created for the McCarthy clan originally, and like most of our famous handwritten books, was compilation of texts from various periods.

Illuminated copy

The Book of Kells is an illuminated copy of the Gospels, and not a compilation. The text was well-known: it was its artistic presentation that was important. But with other Irish books it is the content which is important. Kells was intended for use in a liturgical service. The Book of Lismore is a volume of historical records.

The Book of Lismore contains, for instance, a version of what used to be called The Colloquy of the Ancients, the 12th Century AcallamnaSenórach. A translation of the text by Ann Dooley and Harry Roe is currently available as a paperback from the Oxford University Press World Classics series as Tales of the Elders of Ireland (£8.99). This effectively replaces the more familiar version from the era of the Celtic revival by Standish Hayes O’Grady.

Medieval Christian Ireland

This tale is one of the most extraordinary texts from medieval Christian Ireland, a book from which derives the path of creative literature that runs on to Finnegans Wake and At Swim-Two Birds. In it St Patrick, on his travels round Ireland, comes to what is called the tomb of Finn and brings the ancient pagan Fenian hero alive again to answer the saint’s questions about the past. (My friend Prof. Glyn Daniel used to describe this the record of the “first archaeological excavation in Ireland”.)

In these pages much of the lore and legends of Celtic Ireland are recounted. It ends with the saint enrolling the warrior in the new Faith and blessing his second death.

But at the other end, the Book of Lismore included a version of the travels of Marco Polo from the 13th Century. The Lismore text was written out in the 15th Century – which was not long indeed after the Irish traveller, James of Ireland, the Franciscan accompanied Oderic of Pordenone to the distant realms of China and the Orient, to Cambaluc and perhaps even Tibet and Lhassa.

The Book of Lismore casts itself back into the most remote past of Ireland as well as a vision of the world at the end of the Middle Ages. It provides an overview of the wide intellectual outlook of Gaelic civilisation on the cusp of its final collapse under the hand of Tudor, Jacobean, and Cromwellian violence.

A national treasure indeed, the Book of Lismore will be given an appropriate home by UCC close to where it was created as dark clouds gathered over Ireland.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello