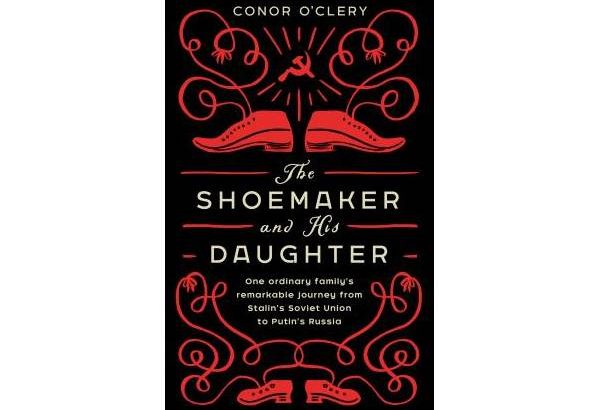

The Shoemaker & His Daughter

by Conor O’Clery (Doubleday 2018)

Conor O’Clery was the Irish Times correspondent in Russia for many years. He married Zhanna Suvorov in Moscow in 1989. His new book reads describes “one ordinary family’s remarkable journey from Stalin’s Soviet Union to Putin’s Russia”.

It records the travails of Zhanna’s extended family through the Russian Revolution, the dictatorship of Stalin, the autocratic regimes of Khrushchev and Brezhnev and the disintegration of the Soviet Union into autonomous republics under Gorbachev and Yeltsin.

Nerses Gukasyan, Zhanna’s grandfather, was the descendant of a noble Armenian family. He was born in 1902 in Martakert in the autonomous Armenian enclave called Nagorno-Karabakh inside the traditionally Muslim Soviet Republic of Azerbaijan.

He supported the revolution and joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). When Bolshevik rule came to Azerbaijan, including Nagorno-Karabakh, in 1920, the commissioners acted ruthlessly to collectivise the larger farms and suppress religion.

Monasteries

All Karabakh’s 220 Armenian churches and monasteries were closed and many priests were shot or exiled. Yet Nerses remained a member of the CPSU to further his career as a judge and because Bolshevik rule promised stability after a period of war and turmoil when Armenians experienced bloodshed on an unprecedented scale in the Ottoman (Turkish) empire.

Following the invasion of the Soviet Union by the Wehrmacht, Nerses enlisted in the Red Army. He was fatally wounded on the borders of Romania in 1944. Thereafter his widow Marietta and her two daughters, Zhanna and Larisa, settled in Grozny in the Caucasus.

This was an area populated by the Chechens. While 30,000 of them served in the Red Army, some had joined units of the Wehrmacht. In one of the notorious purges Stalin carried out more than half a million Chechens were hounded out of their homes and villages into cattle rail-cars and dumped on the frozen steppes of Kazakstan with between a half and a third of them being ‘liquidated’ during the operation.

Stanislav Suvorov, the shoemaker Zhanna later married, and the other residents of Grozny witnessed this operation, but in Stalin’s Russia “no one spoke to strangers about matters that did not concern them”.

The vast majority of Russians were grief-stricken when the death of Stalin was announced. Trained to regard Stalin as their saviour, they felt lost and bewildered without him. They were further disillusioned and upset by the disclosures made by Khrushchev concerning the appalling slaughter of Soviet citizens for which Stalin had been responsible.

Moreover, with Stalin dead the new inhabitants in Chechnya feared that the Chechens might return and claim back their homes and villages.

While Khrushchev eased considerably the shackles of the secret police and other agencies on people, he had a hatred of speculation and profiteering. Thus, when Zhanna’s father sold his car to a neighbour he was charged and convicted of a ‘crime against the Party’ and spent five years in jail.

When Zhanna’s father returned from prison the family, so as not to live under the cloud of his prison sentence, migrated to Krasnoyarsk in Siberia. This was a week’s train journey to the east and there they endured harsh and bitter winters and resided in the vicinity of a silo containing nuclear-armed missiles.

When involved in trips as a tour guide outside the Soviet Union, Zhanna was put under pressure by the KGB to spy on her compatriots.

In due course Khrushchev was succeeded by Brezhnev when conditions in the Soviet Union were so depressing that public drunkenness became an acute social problem. Next the disintegration of the Soviet Union under Gorbachev and Yeltsin led to widespread criminality and conflicts within and between the autonomous republics, the most serious occurring in Nagorno-Karabakh and in Chechnya.

This book illustrates the enormous complexity of present-day Russia. It still remains as in the time of the Tsars a collective of peoples and nations. O’Clery also highlights the lack of freedoms, challenges and physical hardship endured by Russians in their daily lives.

It is frequently claimed that Russians seldom smile or look happy. One finds in this fascinating memoir many reasons for Russian tristesse.