Fr Alan Hilliard

The book of Job is an amazingly insightful work which tries to understand the human condition and the possibility of God. He presents insights into friendship, family, property, money and death. In Scripture, we see him being stripped of all he owns and all he knows and is left with nothing.

God and the devil had a game where the cunning devil said if God inflicted enough struggles on Job, he would reject God and believe no more. Eventually the devil thought he had won, and Job’s reply was “if we take happiness from God’s hand, must we not take sorrow too?”

Job is an unusual book in the bible. No covenant, no law, no clear ten commandments. It’s a story laden with truth. Job is not even an Israelite but, rather, a God-fearing pagan who seeks the truth and will not compromise on it. Truth, we see in this epic, is the best ally of God.

Truth

I remember encountering truth in a prison cell while visiting a young man. He had, what was called then, “the virus”. He lost his confidence, felt a failure and now that he was off drugs, he knew how much pain and torment he caused his parents. I asked him one day when he was weakening and he knew he may not have had long left, did he believe in life after death? He said, without hesitating, “I do.” I asked, “why is your answer so positive?” and he simply replied, “there has to be something better than this.” His answer, his story and his life were like Job’s.

I felt sad that he had come to know God because of all his addiction, pain and hurt. It made me think of the way I had come to know God, which was through so much opportunity and goodness, kindness, example and love. I probably wouldn’t have answered as assuredly as he had. But God is bountiful, and he often pours more on those who are in need.

There is no doubt that the ways of God are a mystery as Job outlines. How some come to know him and others find it difficult to even acknowledge the possibility of God.

One of the Churches greatest, St John of the Cross, lived in the 16th century and had a very tough childhood. He has given me great insight into the nature of faith and belief. When he became a Carmelite, he became part of the renewal of the order and this caused a lot of change and disruption which put him on the wrong side of a lot of people. Like Job, he was tormented. His fellow Carmelites tried to sway him by demanding obedience, the offer of allurements and the threat of punishment. They eventually imprisoned him in a cell that was only fifty to sixty square feet with a little shaft of light entering it. The tiny room was formerly a toilet. Somehow in that place he grew in intimacy with God and felt God’s presence very closely. His writings during this time are extraordinary. On one occasion he says, “Now that the face of evil more and more bares itself, so does the Lord bare his treasures all the more.” He escaped by tying sheets together and made his way out of an upper window. After this, he arrived to a convent where he found refuge. He shared his poetry composed while in prison with the cloistered nuns. The religious knew that they were listening to something sublime.

Silence

One of his greatest lines – which he used continuously with his novices – was, “What we need most in order to make progress is to be silent before this great God with our appetites and with our tongue, for the language he best hears is silent love.”

As a people of faith, we must start dreaming again. And, as Job did, trust in God’s providence and presence. Let’s think about it, let’s pray about it and let’s do something about it.

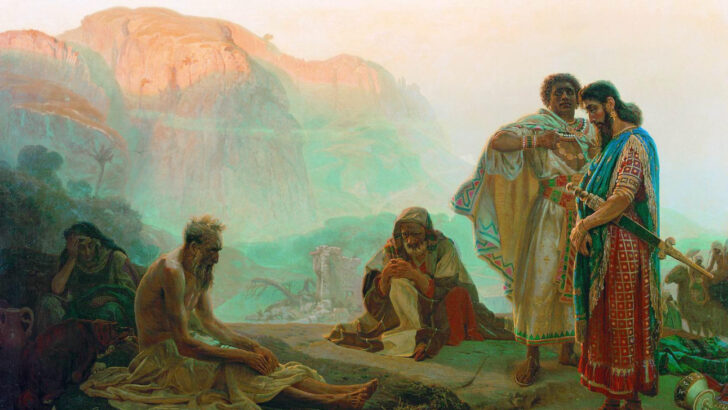

Job and his friends, Iliá Repin (1844–1930)

Job and his friends, Iliá Repin (1844–1930)