Picture the scene: sports day in a Catholic school in Grenoble, France, in February 1856, and a confident 15-year-old student named Henri Didon wins three gold medals. This was no ordinary sports day, though. It was ‘The Olympic Games of Rondeau’.

This quadrennial school festival was inaugurated in 1832, six decades before the first modern Olympic Games would be held in Athens, 1896. Inspired by the French-led excavation of the site of the ancient Olympics, students at the school petitioned that a free day every leap year be consecrated to a miniature re-enactment of the ancient Greek games. For nearly a century that custom was faithfully observed.

Henri Didon, the hero of the 1856 ‘Rondeau Olympics’, grew up to be quite the character. He joined the Dominican order after leaving school, and became famous for his witty repartee and powerful preaching. When the Archbishop of Paris was shot during the Communard uprising of 1871, it was the eloquent Fr Didon who was called on to preach the eulogy.

Responsibility

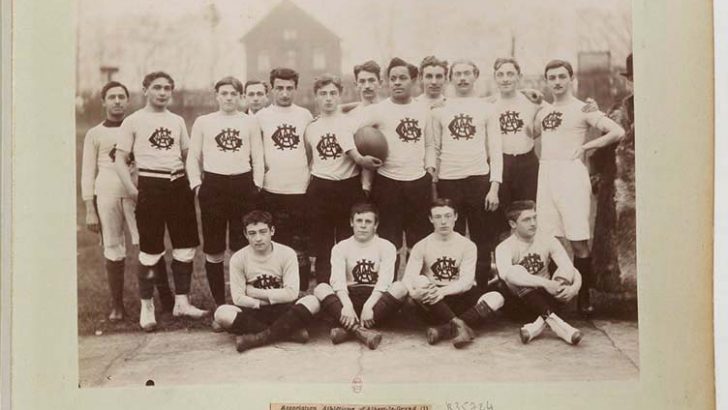

Two decades later Fr Didon, now a middle-aged man, was given responsibility for a Dominican boarding school in Paris, the Collège Albert-le-Grand. It was a mediocre establishment, so the new headmaster applied all his energy to renewing the whole life of the school with individual and team sports forming the core of this renewal programme. He had a running track built, as well as football and rugby pitches. No doubt inspired by his own schooling, he organised sporting competitions too. In 1891, at one such event, the great orator laid out his vision of sport in education in a speech that repeated three Latin words: citius, altius, fortius (faster, higher, stronger). For Didon, these words referred not just to physical achievements, but above all to the moral and spiritual growth at which his educational system aimed.

Educational

As this educational experiment went from strength to strength, Didon began to be noticed by other pioneers in the world of organised sport, especially a visionary young man by the name of Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympic Games. The two became fast friends and collaborators, and Didon encouraged Coubertin greatly as he planned and executed the 1896 Olympic Games in Athens. Didon himself attended those games, taking with him a group of ambitious athletes from his college, and when Catholic athletes gathered for the opening Mass of the Olympics, in the Cathedral of St Dionysius, it was Fr Didon who preached, presenting an explicitly Christian vision for the renewal of societies around the globe by means of the virtues learned in sport. He explained to the gathered athletes that he had brought his students to Athens in order to teach them “to enter into this movement of international unity which seems a first step to the fraternity of peoples which will reach its goal in unity with Christ”.

As for Coubertin, he paid tribute to his Dominican mentor in the motto he chose for the games, three words which have since become synonymous with the Olympic spirit: citius, altius, fortius.

***

The multi-racial aspect of the Olympics

One way in which the modern Olympics differs enormously from its ancient equivalent is the emphasis on the global community: it deliberately welcomes competitors of all “tribes and peoples and languages” (to borrow a phrase from the Book of Revelation). The ancient Greek Olympiad was open to all who spoke Greek, but certainly had no intentions of being pan-ethnic, or even multi-ethnic. In its focus on global fraternity, then, the modern Olympic movement reveals not so much its ancient roots, as its Christian inspiration, as articulated by Fr Didon and many others.

For Didon, the multi-racial aspect of the Olympic movement was not just a theoretical matter. Under his care at the Collège Albert-le-Grand was a Haïtian student of African ancestry: Constantin Henriquez. Henriquez was a model of what Didon’s pedagogy was aiming at: not only was he was a fine student and a leader of men (he became a senator in his native Haïti, as well as chair of the Olympic Committee there), but he excelled also on the rugby field, playing as winger and centre. Captivated by the scenes in Athens, Henriquez began preparing for the 1900 games in Paris. There, with his teammates, he won a gold medal, the first black athlete to do so. Fr Didon wasn’t there to see this triumph – he had died just a few months earlier – but by now the modern Olympic movement, with its admirable blend of pagan and Christian values, was well and truly unstoppable.