Orpen at War: a novel by Patricia O’Reilly (The Liffey Press, €22.95/£19.95)

This is an illustrated biographical novel featuring dozens of Sir William Orpen’s paintings and drawings largely of the Western front in the Great War, in which he was engaged as an official war artist.

Orpen, even then recognised as one of Ireland’s most important artists, was born on November 27, 1878, at Blackrock, Co Dublin. He was educated at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art and at the Slade School of Fine Arts in London. His many distinguished fellow students at the Slade School included Augustus John who became one of his life-long friends.

Orpen taught at the Dublin Metropolitan School from 1882 to 1894. His best-known students were Leo Whelan and Seán Keating, artists in whom his style can be recognised later. He became the most successful commercial portrait artist of his generation.

Following the introduction of conscription in 1916, Keating attempted to persuade Orpen to return to Ireland, where the authorities had failed to impose it. However, Orpen declared his commitment to Britain, the country to which he owed his reputation and fortune. He enlisted and was assigned to rank of major in a war scheme established to produce a pictorial record of the war and to supply pictures for propaganda purposes.

Researched

In this novel, rightly described in the blurb as ‘beautifully written and expertly researched’, Patricia O’Reilly colours in Orpen’s experiences in war-ravaged Northern France. She begins by setting out a tableau of his embarking for the continent. He and the hundreds of other troops filing on to the transports are described singing, ‘It’s a long way to Tipperary’!

In France Orpen was billeted in Amiens, where in a batman-driven Rolls Royce he ventured out to record the devastation after battles and bombings.

Portrait

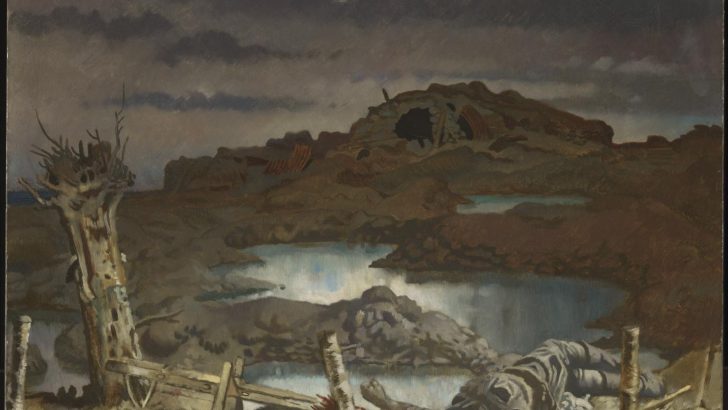

Orpen completed a portrait of a number of senior officers, including Field Marshal Douglas Haig, and Lieut. Colonel Arthur Lee, Censor in France. He painted the war-torn landscapes, bombed villages, rat-infested and slime-covered trenches and dug-outs and nurses ministering to the wounded. He was shocked at the conditions the rank-and-file soldiers had to endure and the pitiful appearance of most of them, particularly after gas-attacks.

However, he was well-aware that this was not an area the War Office expected him to intrude into with his paintings. Orpen’s war ended with his splendid paintings: A Peace Conference at the Quai d’Orsay, The Signing of Peace in the Hall of Mirrors and To the Unknown British Soldier in France.

Orpen returned to France after the war and produced portraits which illustrated the horrors and suffering of the war. Then he published An Onlooker in France (1921), which recorded his disdain for military discipline and respect for the soldiers and airmen who had been his companions and subjects. Resuming his civilian career, he maintained studios in London and Paris and through his portrait practice achieved a huge income.

Orpen married Grace Knewstubon August 8, 1901. They had three daughters. He also had two mistresses and he was a serial womaniser. In colouring in this aspect of his life the author places few restraints on her imagination.

Orpen’s last years were blighted by illness. Not the least of his challenges was what is now known as post-traumatic stress, doubtless caused by his experiences in war-time France. He was always a heavy drinker and he used this to cope with his condition and became a confirmed dipsomaniac. This, and his notorious philandering, caused him to be estranged from his friends and extended family before he died on September 29, 1931.

Paintings

Like so many Irish painters, following his death Orpen’s paintings increased in value year after year. His portrait Gardenia St George with Riding Crop sold at auction for nearly two million pounds in 2001.

Whatever doubts one might have about novelising real people, this book is an agreeable read and, will also (thanks to the colour illustrations which the publisher, not the author, decided to introduce into the text) act as an introduction to an important artist.

Patricia O’Reilly had been told by another Irish publisher in turning down the book, that no one wanted read any more about the Great War. And in any case the subject been “overdone”. On what planet, one wonders, are some people born and reared. The Great War was a disaster for civilisation.

Zonnebeke.

Zonnebeke.