Fr Conor McDonough

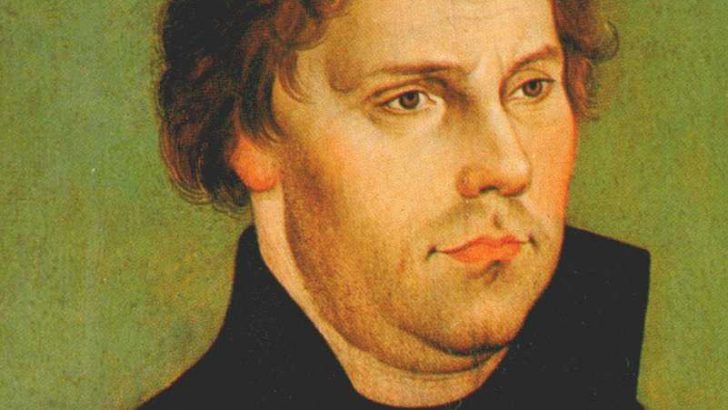

‘Post tenebras lux’ (‘Light after the darkness’), the motto of Calvin’s Geneva, is proposed by some as a summary of the Reformation. After the darkness of the Middle Ages, the previously hidden light of the Word of God is unleashed by Luther and his followers who come armed with vernacular Bibles, pulpits and printers.

Needless to say, this simplistic scheme is far from accurate. Almost none of the Reformers’ positions on the accessibility of Scripture were original. Already in 813, the Council of Tours decreed that priests should preach in the language of the people, and although this decree wasn’t always put into practice, from the 13th Century on Europe saw an explosion of vernacular preaching, especially by Dominican and Franciscan friars.

As for translations of the Scriptures, it’s true that this was a controversial issue on the eve of the Reformation (especially in England), but the theory and practice of Bible translation into the language of the people is as old as the Church. The Latin Bible used in the medieval West was originally such a translation, carried out by St Jerome. The 9th-Century English king, Alfred the Great, patronised and participated in the translation of various books of the Bible into English. Around the same time Ss Cyril and Methodius were evangelising the Slavic peoples, and they didn’t hesitate to begin translating the Scriptures into the language of the Slavs, inventing a special alphabet for that purpose. Later on, but still well before the Reformation, we find thoroughly Catholic and uncontroversial translations of the Scriptures into Italian, French, and German.

Rich body

Besides straightforward translation, the Middle Ages abounded in texts and images inspired by the Bible, often specifically designed to be accessible to laypeople. In the Irish language there is an immensely rich body of biblical poetry, such as the 10th-Century poem, ‘Saltair na Rann’, which recounts a biblical history of humanity from creation to the end times.

The cathedrals of Europe were themselves ‘translations’ of the Scriptures, communicating its narratives through luminous windows and dazzling painted sculpture. And in the century before Luther, the citizens of English towns were regularly entertained with ‘mystery plays’ which re-enacted a wide variety of Bible scenes.

These plays, organised by guilds of craftsmen, used costumes, props and pyrotechnics to amuse and edify, and the language of the actors often matched the dialects of the spectators. Curiously, these immensely popular biblical dramas were systematically suppressed by Protestant monarchs and parliaments.

We ought certainly to admire Protestant devotion to the text of the Scriptures, but we Catholics shouldn’t necessarily feel inferior in this regard, especially since Christianity is not a religion of the book. We follow the Word Incarnate, Jesus Christ, who taught not with his voice only, but with his facial expressions, his gestures, and with his whole body on the Cross.

At its best, the pre-Reformation Church made of the Scriptures not just a black and white text to be read, but a full-colour, flesh-and-blood world to be inhabited.

As part of my studies at the University of Fribourg (Switzerland), I’ve spent much of the last year reading the writings of John Calvin, especially his Scripture commentaries. Calvin, part of the second generation of the Reformation, was a passionate educationalist, and made sure that elderly clergy as well as young students regularly attended his classes, where he would carefully comment on books of the Bible, verse by verse. All this might sound like a Protestant invention, but what I found was that Calvin’s works bore striking parallels to those of St Thomas Aquinas, the great 13th-Century Dominican theologian who, throughout his lifetime, carried out the same careful work of Scripture commentary. Thomas and Calvin may be separated by three centuries and a schism, but the same unfailing light shines in their works.

It’s fascinating to see how various Protestant groups are celebrating the anniversary of the Reformation. The Reformed Church of Geneva, for example, is inviting its young people to ‘rock the Geneva Arena’ at a celebration concert which promises ‘a pounding bass line, sick beats and acrobatic dance moves’. I’m not sure Calvin would entirely approve. When he ruled Geneva, those who ‘spun wildly around in dance’ were punished with three days in prison…