In a recent book, Frostquake, the English writer Juliet Nicolson recalls the winter of 1962-63, which was the coldest for perhaps 80 years. Everything froze, communications broke down, lights and heating went out. When the thaw came, in March of 1963, it is Ms Nicolson’s thesis that Britain – and elsewhere, too – woke to a changed world. The ‘1960s’ began after that thaw, with the Beatles, the Profumo affair, the contraceptive pill made widely available, and the launch of the ‘permissive society’.

Changes

The year 1963 would bring many other changes, including the visit of President John F. Kennedy to Ireland and later in the year, his tragic assassination at Dallas. The thawing climate of 1963 would also bring about the changes to the Catholic Church introduced by Vatican II, the first being the switch from a Latin Mass to Mass in the vernacular, followed by the many other measures of what was called aggiornamento – bringing up-to-date.

Juliet Nicolson – granddaughter of the writer Vita Sackville-West – thinks that the post-thaw social changes begun in 1963 were all to the good. Yet, maybe as the Chinese leader answered when asked 200 years later about the outcome of the 1789 French Revolution – “it’s too soon to say”.

On Vatican II, there were positive changes, but “it’s too soon to say” what may have been some of the longer-term outcomes.

Impact

Will Covid-19, when we emerge from it, have a similar impact? Will we awake to a different world? Are we seeing signs of that already – a world without travel, or with much less of it? A world in which we are more inclined to be confined to our national boundaries?

A world in which the state tracks us ever more intimately, keeping data on all our movements, requiring ‘passports’ for every activity – including more state control of religion?

The ice-floes are changing the contours politically, already: Scottish independence, a form of re-united Ireland already on the radar. It’s evident that when the ‘thaw’ eventually comes, everything will be different. We had better be ready for it.

***

The Cheltenham race festival was a breath of fresh air during St Patrick’s week – and a great triumph for the Irish. Having no crowds seemed odd, and yet it allowed us a purer focus on the turf: and the clear sight of a rider in perfect harmony with the horse is surely one definition of poetry in motion.

I always think of the racecourse as an inclusive and even ecumenical place, as expressed by the fine ballad about the ‘Galway Races’, where “the Catholic, the Protestant, the Jew, the Presbyterian” mingle together in an atmosphere of jollity. In times gone by, Irish priests were often seen, in clerical habit, at the Cheltenham races. Far from scandalising, a day at the races was considered a harmless hobby for a hard-working man of the cloth.

Tipperary woman Rachael Blackmore was indeed brilliant and a great inspiration; the wholesome normality of her general attitude, and that of her family, was so much in contrast to all the gloomsters and doomsters who have prevailed over the last year.

Although her stunning equestrian performance evoked my own misery-memoir moment: I’m still resentful that as a youngster I wasn’t allowed riding lessons at Iris Kellett’s famed Dublin stables – because they cost seven-and-sixpence each!

In St Joseph’s workshop

Raphael, Caravaggio, Albert Dürer, Andrea Mantagna, Georges de la Tour, John Everett Millais, Robert Campini, Guido Reni and Giuseppe Maria Crespi are among the many artists who have portrayed Joseph, a saint who inspires the greatest devotion.

De La Tour’s portrait of St Joseph, in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Nantes is bathed in exquisitely warm colours illuminated by candlelight, depicting the angel appearing to Joseph to tell him of Mary’s pregnancy. Caravaggio’s Joseph, at Rome’s lovely Galleria Doria Pamphilji, is wonderfully delicate and vivid, portraying St Joseph as guardian of the Holy Family.

Appealing

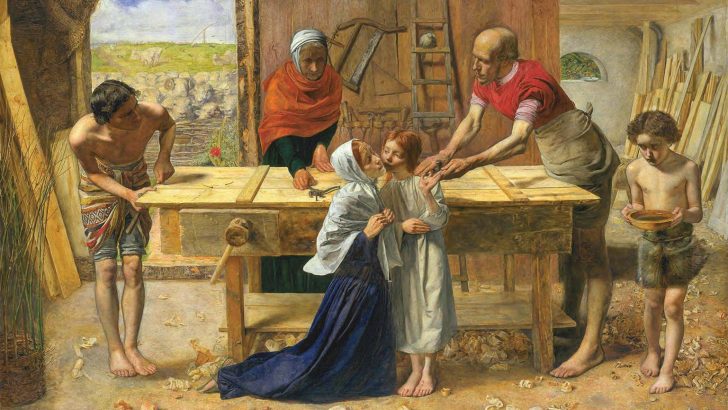

But Everett Millais’s picture of Joseph, at London’s Tate Gallery is enormously appealing and almost contemporary: it’s a portrait of St Joseph at his carpenter’s trade, entitled Christ at the House of His Parents (The Carpenter’s Shop). Millais was part of the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood who sought to bring Christian ideals into ordinary lives, and his picture of Joseph is as guardian, protector, and practical breadwinner of the family which here includes John the Baptist.

Mary Kenny

Mary Kenny Christ in the House of His Parents by John Everett Millais in Tate Britain in London.

Christ in the House of His Parents by John Everett Millais in Tate Britain in London.