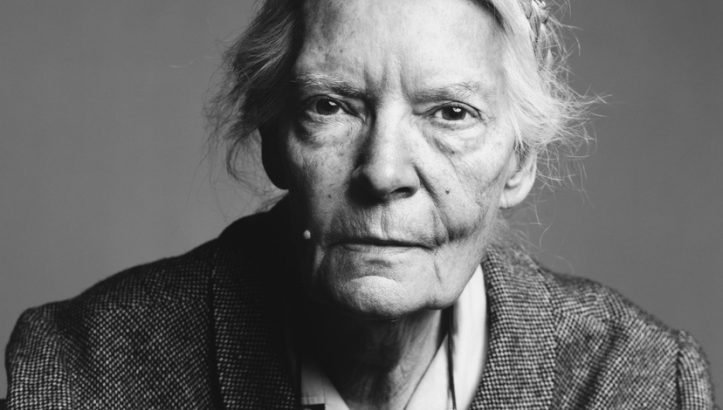

Dorothy Day is alleged to have said: “Don’t call me a saint; I don’t want to be dismissed that easily!” A new biography on her by her granddaughter, Kate Hennessy, Dorothy Day – The World will be saved by Beauty: An Intimate Portrait of my Grandmother, will, I believe, go a long way in preventing anyone from turning Dorothy Day, soon to be officially canonised by the Church, into what she feared, a plaster-saint who can be piously doted-upon and then not taken seriously.

We’re all, I’m sure, familiar with who Dorothy Day was and what her life’s work was about. Indeed, Pope Francis in addressing the US Congress, singled out four Americans who, he suggests, connected spirituality to a life of service in an extraordinary way: Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Thomas Merton and Dorothy Day.

This new biography gives us an honest picture of who this remarkable woman actually was.

This book is extraordinary for a number of reasons: Kate Hennessy is a very good writer, the book is the product of years of research, she’s Dorothy’s granddaughter and had a very close and special relationship with her, and she manages in telling Dorothy’s story to keep both a healthy critical and aesthetic distance. Her insight is both privileged and rare, privileged because of her intimate relationship with Dorothy and rare because most authors who are that intimately tied to their subject cannot maintain a balanced critical distance.

No easy task

Hennessy admits that doing this was no easy task: “That is the danger of holiness on your own doorstep, in your own family. Either you cannot see it for the view is too close, or if you do, you feel you haven’t a chance of being the person she was. You feel it is a sad mistake that you are related.”

And that combination makes for an extraordinary book that lets us see a side of Dorothy Day we would never see otherwise. Beyond this being a close-up of Dorothy Day, Hennessy shares stories about some of the key people surrounding Dorothy: her relationship to the man who fathered her child, Forster Battenham, with whom she maintained a life-long friendship. Hennessy’s biography shatters the myth that upon her conversion Dorothy coldly and forever turned her back upon this man. Not true.

They remained close their whole lives and Forster, until her death, remained an intimate companion and a faithful supporter.

Central too to this biography is the story of Dorothy’s daughter, Tamar, who, while vitally important in Dorothy’s life, is unfairly absent in virtually everything that’s known about Dorothy in the popular mind. Tamar’s story, which holds its own richness and is not incidental to the history of the Catholic worker, is a critical to understanding Dorothy Day.

There’s no understanding of Dorothy without understanding her daughter’s story and that of her grandchildren. To understand Dorothy Day you also have to see her as a mother and grandmother.

Hennessy shares how, when her diaries were opened some years after Dorothy’s death, Tamar initially was bitterly resistant to having them released for publication and how that resistance was only lifted when, thanks to the man who transcribed them, Robert Ellsberg, the family and Tamar herself realised that her resistance was rooted in the fact that Dorothy’s diaries themselves were unfair in their neglect of Tamar’s story and the role of her story within the bigger narrative of Dorothy’s life, work and legacy.

The book is a story too of some of the people who played key roles in founding the Catholic Worker: Peter Maurin, Stanley Vishnewski, and Ade Bethune.

This isn’t a story that follows the classical genre for the lives of the saints, where form is often exaggerated to highlight essence and the result is an over-idealisation that paints the saint into an icon. Hennessy highlights that Dorothy’s faith wasn’t a faith that never doubted and which walked on water.

What Dorothy never doubted was what faith calls us to: hospitality, non-violence and service to the poor. In these things, Dorothy was single-minded enough to be a saint and that manifested itself in her dogged perseverance so that at end she could say: “The older I get the more I feel that faithfulness and perseverance are the greatest virtues – accepting the sense of failure we all must have in our work, in the work of others around us, since Christ was the world’s greatest failure.”

That being said, her life was messy, many of her projects were often in crisis, she was forever over-extended, and, in her granddaughter’s words: “She was fierce, dictatorial, controlling, judgmental, and often angry, and she knew it. It took the Catholic Worker, her own creation, to teach her her lessons.”

This is hagiography as it should be written. It tells the story of how a very human person, caught-up in the foibles, weaknesse and mess that beset us all, can, like St Brigid, cast her cloak upon a sunbeam and see it spread until it brings abundance and beauty to the entire countryside.

Fr Ronald Rolheiser

Fr Ronald Rolheiser Dorothy Day

Dorothy Day