Smitten Soul: Illuminating the Dark, by Gabriel Fitzmaurice; with paintings by Brenda Fitzmaurice

(Salmon Poetry, €12.00)

Seamus Cashman

“Am I going to Mass on Sundays?” Mary asks in a string of questions, and the poet remarks, “how the good are frightened of their Church”.

The poem, from Gabriel Fitzmaurice’s latest collection, is called ‘Alzheimer’s Disease’ and it carries blunt, even frightening, closing lines. Gabriel Fitzmaurice doesn’t baulk at bluntness, a dark side feeds through his often seemingly easy rhythms and rhymes. Making them heard.

In the next poem, the bluntness of the word will trouble ears innocent and guilty and the poem quietly shouts: “…it’s no excuse / to plead that in the past we didn’t know.”

Among Ireland’s best known poets, and one of our leading translators of Irish poetry into English, Fitzmaurice’s work is characterised by crystal undercurrents of melody that flow from his skill with rhythmic lines, and he is master of the craft of rhyme. He has written extensively for children too. And among his 50-plus published books are several major anthologies.

This new collection of his work, Smitten Soul: Illuminating the Dark is the poet’s own selection of spiritual poems from a lifetime of writing.

If someone asks why you believe in God, the American philosopher Joseph Kupfer suggests it might better be answered with a poem than with an argument. The premise being that art, like religion, can persuade where logic fails; that metaphor and religion share ‘manifestation’ in ways inexplicable and even contradictory. This volume in spite of its solemn title, both manifests and satisfies, but also entertains and is always illuminating. It is a poetic soul journey for our time.

With illustrations that remain in the eye and invite reflection on the texts, the poems seem to float between mists, mountains and clear skies in an onrush merging of two centuries, one ending, the other now in its teens.

Poems from the 60s to the present day both hold true. In ‘The Day Christ Came to Moyvane’, word usages such as ‘tinker man’ have changed; we change language day by day – note the ‘passings’ of us humans nowadays; ‘they’ don’t seem to like the integrity or bluntness of ‘death’ or ‘died’ any longer. Why?

Poems are always about language, no matter the subject. We no longer get our umbrellas fixed and we recycle the pots and pans, but the poem wakens a bigger story.

Beginning with a clear and personal vision poem about guitars and “doing my thing”, the volume ends with a fine dual-purpose piece on love (its capital letters call to the divine, but read in lower-case, human love is addressed here too). First and last poems in a collection are important markers for a poet. And here midway, simplicity offers a believer’s truth in five short lines: “It’s easy to dismiss it / In the light of day / But when dark descends / And you need help / You pray.”

The dark is alive in these texts, energetically so. In poems like ‘A Catholic Speaks Out’ – “I’m through with cover-ups, I’m through with Rome, / From now on I’ll worship God at home.” In a superb sequence on Knockanure Church where icons of modernism in the 1960s are destroyed or defaced, the poet records Imogen Stuart’s triumphant and tall ‘Cross’ being vandalised, “cut up and bolted to the wall, …/ in spite of all our pleas, / God and art no longer all in all, /… A broken image, broken like us all.”

In another sonnet, Oisin Kelly’s ‘Last Supper’ masterpiece carved in teak is defaced, a notice thumb-tacked to it “by some boor”. Then, for the poet. But for us now. Note that as I write this piece, a homeless man on Dublin streets is kicked in the face (recorded on a mobile phone) – an act of boordom half a century on. Fitzmaurice’s ‘Smitten Soul’ collection here, and its faith base, challenge not through presumed authority, but through awareness, through poetic expression.

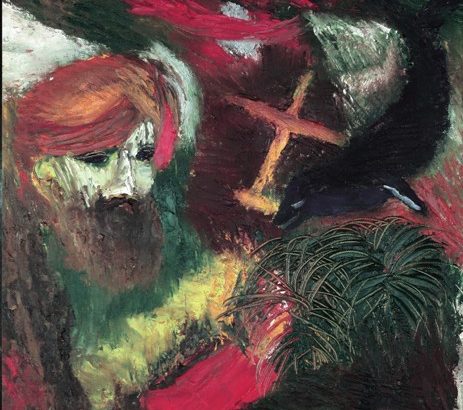

Energetic, happy, tragic, documentary, these are poems by a believer, works of merit, of effectiveness and of beauty created in word, rhythm and rhyme – this poet has long been a master of his art. Here too are terrific embellishments in illustrations by Brenda Fitzmaurice. The artist’s uses of strong colours painted in ‘artisan oils’. Deep reds, greens, and blues predominate in vigorous figurative images and in images of darkness in the ‘smitten soul’.

Unusually however, these same images are also reproduced additionally as faded greying tints in monochrome, as if shadows on a wall. These create mystery, draw in the reader, invite meditation on facing texts. This dual mode of reproduction was the idea of designer Siobhan Hutson of Salmon Poetry. The book is presented as a treasure, and it is.

My one carp with poet and publisher is that there is no biographical note on the illustrator whose work is as important to the book as the poems are, for together they make a volume that will generate conversation and will grace readers’ tables as well as bookshelves.