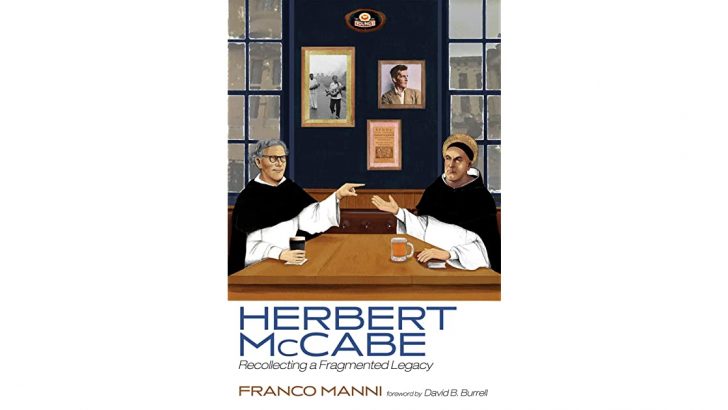

Herbert McCabe. Recollecting a fragmented legacy

by Franco Manni, foreward by David B. Burrell (Cascade Books, £50.00/$26.98)

Frank Litton

One man in his time can touch many minds and souls. Anthony Kenny, Alasdair MacIntyre, Stanley Hauerwas, David B. Burrell, Brian Davies, Rowan Williams, Denys Turner, are among today’s most eminent philosophers and theologians. All have produced major academic works. And all acknowledge the significant influence of the Dominican Herbert McCabe on their work.

Herebert McCabe (1926-2001) was not an academic. He published only four books in his lifetime, none of which were traditional academic treatises, replete with footnotes. What he was, as his order required, was an exemplary preacher.

What is good preacher? Obvious, surely: they make the Word of God come alive in the hearts of their listeners. It is a little more complicated, at least, for Catholics. The Word always comes to us as interpreted. The understanding of the early Christians whose witness we read in the New Testament was, like ours, limited and conditioned by the circumstances of their time. We cannot share their point of view.

What we do share is their Faith and that of the many generations that come between us who pondered that witness as they put it into practice in their particular place and time. A good preacher is a ‘traditionalist’, loyal to the institution that sustains that tradition.

Tradition

We need tradition because change is inevitable. The work of tradition is the never-ending translation of what we have learnt into terms that guide us in the new landscapes into which our journey takes us. The task may be seen as the merging of horizons. What is seen in one horizon is placed in a new horizon. It remains what it is but is now seen in a new perspective.

McCabe excelled at this. To give two examples. He placed Aquinas in the philosophical horizon opened by Wittgenstein to provide a robust restatement of classical theism. He gave new life to ‘virtue ethics’. He made a distinction between a manual and a rule book.

A learner of a game is greatly assisted by a manual that explains good moves and the skills required to execute them. They also need a rule book to teach what is forbidden because it is not playing the game. The Utilitarian and Kantian strands that dominate ethical discourse focus on the latter. McCabe brought the Aristotlean tradition as developed by Aquinas to new life in putting human flourishing and the virtues that served it centre stage.

Scripts

He prepared his sermons, lectures, papers with meticulous care and always spoke from a script. He was a lucid, precise, speaker, illustrating abstract concepts with witty examples. (I can testify to this; McCabe had many Irish friends and visited Dublin regularly. I had heard him speak several times in the 1970s.) After his death, his confrere Brian Davies OP, now a professor of philosophy at Fordham University, assembled these scripts for publication in six volumes.

All the major items on the theological/philosophical agenda are included, ably summarised by Manni”

These, together with interviews with academics and friends provide the basis of Franco Manni’s invaluable study. He provides us with an epitome of McCabe’s work. Its extent, range and coherence is impressive. All the major items on the theological/philosophical agenda are included, ably summarised by Manni with well-selected quotations that convey McCabe’s arresting style.

The foundations of our modern world were laid in the 17th Century: philosophy by Descartes, politics by Hobbes, science by Galileo. The complex interweaving of these elements was always a work in progress producing new and unexpected patterns. The tapestry has been unravelling for some time. The rate of its undoing increases under the impact of globalisation and climate change.

Reading Manni’s pages, one recognises just how relevant McCabe is in this context. This book is a sure guide to McCabe’s own writings where readers will discover for themselves why he was admired not only by so many eminent academics, but also many more ordinary Christians, whom he saw as his main audience.