If Luther created our world, he didn’t mean to, Brad Gregory tells Greg Daly

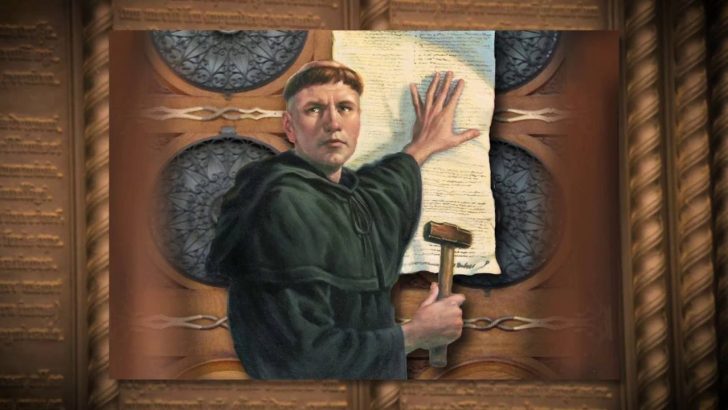

It’s something of a cliché to say that Martin Luther never intended to create the storm he generated, and that matters took their own momentum, but for Brad Gregory, this could hardly be more true.

“Luther initially was just objecting to what he regarded as excessive promotion and misunderstanding among the laity about indulgences,” says Notre Dame University’s Dorothy G. Griffin Professor of Early Modern European History. “Indulgences are widespread in late medieval Europe – they are very popular with the laity. It is a myth and a mistake to think this was a clerically-driven scam, nothing but fundraising and pulling the wool over the eyes of the laity. They’re the ones in effect who were driving the demand.”

Luther, he says, was concerned that indulgences were not well understood and that some indulgence preachers were taking advantage of that lack of understanding to maximise fundraising.

Reaction

The 95 theses themselves didn’t quite spark the Reformation in the way we tend to imagine it, he continues: “It’s really the printing of those and the reaction to them that leads to the unexpected enthusiasm on the part of those who had been concerned with reform and long-recognised problems within the Church, on the one hand, and also those who see in the Theses some implicit claims by Luther about what the power of the Pope supposedly is and is not.”

This in turn, he says, becomes a bridge to the deeper and more threatening questions about authority in the Church that defined the controversy from 1518 through 1521.

Printing was key to this. “It’s the first mass communications phenomenon in Western history, and a lot of people have drawn analogies – and I think they’re helpful ones – between the kind of revolution in communications that has been a result of our own online and digital environment, over the last say 20 years, and popular print in the 1520s in Germany,” he says.

Although printing had been around for over half a century, it had never been leveraged in this way before, Prof. Gregory says, describing it as an innovation of Luther’s to put “matters of controversial religious and theological content into the vernacular language, so that he was encouraging every ordinary person who could read”.

Luther’s pamphlets reached beyond the literate, he adds, noting how in villages there would usually be somebody who could read who would be called upon to read the pamphlets aloud in the village square.

“There’s no question that printing is absolutely crucial, and that’s what makes Luther’s reputation,” he says. “In the middle of 1517 almost nobody knows who Martin Luther is, and by the middle of 1520 he is the most published author since the invention of the printing press. It’s an astonishing rise out of nowhere in those terms.”

*****

Prof. Gregory’s latest book, Rebel in the Ranks: Martin Luther, The Reformation and the Conflicts that Continue to Shape our World picks up on a central point in his 2011 book The Unintended Reformation: How a Religious Revolution Secularised Society in identifying how the related factors of printing, vernacular literature, and the principle of the private interpretation of Scripture meant that fragmentation was built into the DNA of the Reformation.

“I think this is the key – this is what Luther does and the stand that he takes that ends up being so incredibly consequential. It’s not as if Luther’s movement is going along for a few years and then suddenly people start to dissent – it’s right from the beginning,” he says, relating how Wittenburg colleagues of Luther such as Andreas Karlstadt and Gabriel Zwilling quickly ran with their own readings of Scripture, taking the Reformation in radical directions of which Luther disapproved. Luther, who had been in protective hiding, rushed back to Wittenburg in spring 1522, and effectively ran Karlstadt out of the town; Zwilling acquiesced to Luther’s vision.

“So the emphasis on Scripture Alone proves to be a completely unworkable principle for any sort of unified reform of the Church,” Prof. Gregory says, “because it simply displaces the question about authority and interpreting Scripture back to the respective reformers or interpreters who then argue with one another over what turns out to be the divisive points, like the understanding of the Eucharist between Luther and Zwingli, like infant baptism between both of those reformers and all of the groups that collectively then become known as Anabaptists, and so on.

“The story of Protestantism is the story of disagreements about what God’s word means, who has the authority to say so, and you know ‘if I don’t like your interpretation or my group doesn’t, then we’re just going to go off on our own and do our own thing’,” he adds, observing that the problem was spotted at the beginning in some senses, but that with few exceptions they never stepped back and saw that the principle itself was the core problem.

“Those Protestants in the 16th Century who take a step back and say the problem is the principle itself, it just doesn’t work – they are the ones who end up either returning or becoming Catholic,” he says, remarking, “that’s not the typical version.”

*****

It’s important to understand, he says, just how high the stakes were for the Reformers, and why challenges to interpretations were often met so furiously.

“It’s not just a kind of distant, aloof, reading of scripture. These guys are not simply interested in interpreting the Bible because they want to know what a particular verse in the Gospel of Luke means,” he says.

“This is also intimately connected to their devotional lives, to their experience of what they understand God’s grace and salvation to be, to their experience of community and the way in which worship is carried out, and so forth. It’s not a purely detached, philological scholarly interpretation of Scripture; this is about their relationship with God. And so if you’re attacking somebody’s interpretation of Scripture, you’re also really attacking their religious lives as a whole.”

It takes a very long time before the conflicts that the Reformation sparks off and fuels settle down, and modern concepts of tolerance come to the fore.

“There are impulses in the 17th Century where you can find that attitude, but it would be a mistake to say that after the uproar of the English Revolution in the British Isles and after the Thirty Years War was done in 1648, all of the leaders of Europe kind of decided ‘Ah! What we really need is modern liberalism and we’re going separate out religion and make it a private thing, and so forth’,” he says, acknowledging that that is – more or less – what eventually happens, though over a much longer period.

Pioneers

The pioneers in this respect were the Dutch, he explains, who in the late 16th Century realise, as he puts it, that “Militaristic Calvinism is not the way we want to go, and we also don’t want Counter-Reformation aggressive post-Tridentine Catholicism, but what we definitely want is to get rich, and we have a chance to do that as a commercial empire.”

And so a sort of religious toleration – albeit not an impeccably robust sort – was born. “They realise that that kind of religious toleration is simply good for business, and if you can allow people to worship the way that they want to in private, while still maintaining – as the Dutch do – public support for a Calvinist Church, well, that turns out that Catholics and Lutherans and Mennonites prefer, surprise, surprise, not being persecuted.”

Mass and other forms of Christian worship could take place behind closed doors, he said, while public conflict was kept to a minimum and the Dutch as a whole participated in their 17th-Century commercial miracle.

“What is eventually going to of course become modern industrial capitalism and consumerism essentially what papers over and makes it easier, let’s say, for Christians with the legacy of conflict and violence behind them to in a sense agree to disagree, because can’t we all agree that it’s nice to be able to shop and buy the things that we want to buy, regardless of our religious differences,” he says.

This, he argues, is a key step towards modern secularisation, noting that while the Dutch were the most important figures in this development, others fumbled with less success towards similar principles of tolerance during the period, matters being made more difficult by rulers fearing that they would be called to account by God for not having protected the Church and Christian truth.

“European civilisation was basically dragged into modern toleration. It did not embrace it in an enthusiastic, robust way,” he says.

At the same time, the fragmentation that was endemic in Protestantism was sowing the seeds for Christianity in general looking increasingly irrelevant, with some Catholic observers making that point polemically from the 16th Century, criticising Protestantism for the divisions that had arisen from it.

“Of course they don’t draw from this the conclusion that Catholicism also could somehow be put under the same sceptical gaze or people could throw up their hands about it as well – there are Protestants in this Revolution who would look around themselves and say you can make anything you want out of the Bible and really the result is or should be a kind of scepticism,” he says.

This insight has really only started to corrode and bite in more recent times, he says, especially in the last half century or so.

“For a long time the sort of rhetoric of it throughout the Enlightenment was ‘Clearly the problem was these stupid religious people, arguing over these minute points and the violence that comes from that and so forth when all you need is the clear light of reason to tell us all how exactly people should live and so forth’,” he says, adding that this rhetoric is still common in the contemporary public square.

“The problem with that, is that the content of reason and what it is to be rational and what are rational reasonable understandings of human nature and human society and human morality have never been a matter of consensus any more than the disagreements that have arrived through the Protestant emphasis on Sola Scriptura (‘Scripture alone’),” he says, concluding that “reason has not done what scripture failed to do – it’s adding to the problem”.

The extent to which consensus understandings of such things have broken down can be shown in today’s arguments about what constitutes a person or a family, he says – these being what debates about abortion and same-sex marriage, for instance, are really about.

Such arguments, he says, are far beyond the kind of arguments Catholics and Protestants had over the form of the Church or the nature of the Sacraments.

*****

There’s a clear echo in Prof. Gregory’s work of the thesis of the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre who argued in 1981’s After Virtue that late medieval philosophical developments and the Enlightenment as a whole have left us with a pre-modern language of morality masking an absence of agreement over what our moral language means.

“I’m majorly influenced by MacIntyre,” says Prof. Gregory. “I think there is probably no way I would have arrived at my interpretation of the Reformation era without the influence of MacIntyre and I think if you take MacIntyre’s After Virtue and you combine it with The Unintended Reformation then you’ve really got a very powerful long term interpretation – it seems to me – of what happened to society and morality and politics.

Analysis

MacIntyre’s analysis skips from late medieval scholastic philosophy to the Enlightenment, Prof. Gregory says, adamant that the intellectual shifts and divisions of the Reformation period are part of the same story.

“There are so many tragic ironies in the history of religion,” he says, observing how “the thing that’s meant to bind us very often ends up dividing us, the thing that’s meant to be collective ends up contributing to the rise of individualism and atomisation”.

One key irony is that although Luther is often hailed as a liberating figure, the liberty we current have is one that would have been anathema to him, with this being his legacy only by means of a long and tortuous route.

“Now in the sense that things that have intervened have led to where we are today, yes, but in the sense that Luther wanted to bring that about or that he would have approved of where we ended up – absolutely not,” he says.

“Luther’s idea of freedom for a person is that because you’ve been saved by God’s grace you are now free to devote yourself to worry-free endless service to your neighbour,” he says, with this service being engaged in without any need to consider whether your actions are in any way contributing to your salvation. Describing this as “a paradoxical freedom”, Prof. Gregory says: “It’s like an enslaved freedom of Christian service and I think everybody can agree that that’s a long way from ‘do your own thing’ or ‘I’ll buy as much as I want up to my credit limit’.”

Commenting on how the Catholic world has engaged ecumenically with what Luther was saying, he notes that the Second Vatican Council adopted such characteristic features of the Protestant Reformation as vernacular liturgy, the orientation of celebrants towards the congregation, and a greatly increased emphasis on the role and vocation of the laity in the Church and the world.

At a theological level, he adds, for decades theologians have recognised that “many of Luther’s emphases on God’s grace and so forth had the right impulse”, even if they were pushed in excessive ways that should be rejected.

However, he says, the real story of the relationship between Catholics and Protestants, is “their tremendously diminished influence in wider society in ways that I think have made them recognise one another as allies, not withstanding whatever doctrinal or religious differences might remain”.

Describing these differences as paling in comparison compared to the need to find common ground against the more dangerous and insidious trends of a secularised society, he also says that it is, quote simply, “a more Christian and Christlike thing to do to be charitable and get along with one another and be friends than it is to hold one another at arm’s length and continue to polemicise in ways that our predecessors did for centuries”.

Greg Daly

Greg Daly