The GAA and the War of Independence

by Tim Pat Coogan (Head of Zeus/an Apollo Book, £20.00)

The Gaelic Athletic Assoc–iation (GAA) promotes, across the whole island of Ireland, Gaelic football, hurling, ladies’ Gaelic football, camogie and handball.

However, it does not concern itself solely with organising these sports. With the Irish language, Irish music and dance, and Irish folklore it is an integral part of our Irish heritage.

Moreover, when the need arises, at different times to a greater or lesser extent, it wraps itself in the green flag of Irish nationalism and patriotism. And, as the influence of the Catholic Church declines, it is becoming more and more a cornerstone of Irish society – perhaps even the cornerstone, especially in rural communities. It builds a sense of local life with local people essential to the identity and identity of many people’s sense of themselves. The pews are emptying, the stadiums are packed.

That sense of identity is at the heart of journalist and historian Tim Pat Coogan’s new book – significantly published by a British publisher.

As he relates, the GAA was founded in Thurles, Co Tipperary, on November 1, 1884. From the outset it was infiltrated by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). This organisation had been established in 1858 and organised an unsuccessful rebellion in 1867. Thereafter it determined to promote its separatist aims by secret means, not least by infiltrating strategically important institutions, such as the GAA.

The co-founders of the GAA were Michael Cusack, Maurice Davin, J.K. Bracken, John McKay, Joseph O’Ryan, Thomas McCarthy and John Wyse Power.

Acceptance

A teacher from Co Clare and a member of the IRB, Cusack was a key-figure in the early years of the organisation. He invited Archbishop Thomas William Croke to be patron of the new athletic and sports organisation and the latter’s acceptance, dated December 1884, became the GAA’s Magna Carta.

Croke soon made it clear that he did not wish the new sporting body to be a tool for the IRB to be deployed in the promotion of revolution and violence. His involvement was providential. Following attempts by the IRB to take over the Central Council in 1887, the GAA threatened to dissipate into scores of pro- and anti-IRB factions.

Croke managed to heal those serious rifts and to ensure that the GAA did not become the property of the IRB and that it subsequently attempted to steer clear of party politics.

It was inevitable that members of the GAA would be caught up in the revolutionary period 1916–23. Many of those who rallied to the Irish Volunteers in 1913 were members of the GAA. Of the 2000 participants in the Easter Rising in 1916, 300 were members of the GAA. Later they were prominent and key-figures in the war of independence and the subsequent civil war.

As the war of independence increased in intensity, the British authorities made little distinction between members of the GAA and those of the IRA. This was made clear when in a reprisal for the assassination of intelligence officers in Dublin the Crown forces launched an attack on a fixture at Croke Park on November 21, 1920, which left 30 civilians dead and scores injured. Such was the indiscriminate and ferocious nature of the attack that it became known as ‘Bloody Sunday’.

Later members of the association were to the fore in the healing process following the civil war.

With the community in which it flourished the GAA and its members were subjected to discrimination and injustice in Northern Ireland from its beginnings in 1921. In more recent times the so-called ‘Troubles’ were particularly challenging. At that time loyalist murder gangs claimed that members of the GAA were ‘legitimate targets’ and as a result some players and administrators were assassinated and pitches and property were systematically vandalised.

Five of those who died in the hunger-strikes of the early 1980s were GAA members. This prompts the author to provide a valuable account of that tragic period and the manner in which the GAA authorities successfully managed those times.

Following the Good Friday Agreement the official environment in the North vis-a-vis the GAA greatly improved. However, it continued to be far from ideal, as is evidenced by the saga concerning the attempt to re-build Casement Park.

This book is an important account of the role of the GAA and its members in the war of independence.

At times the author’s asides are even more interesting and informative than the main narrative, wherein uncharacteristically there are a few Homeric nods.

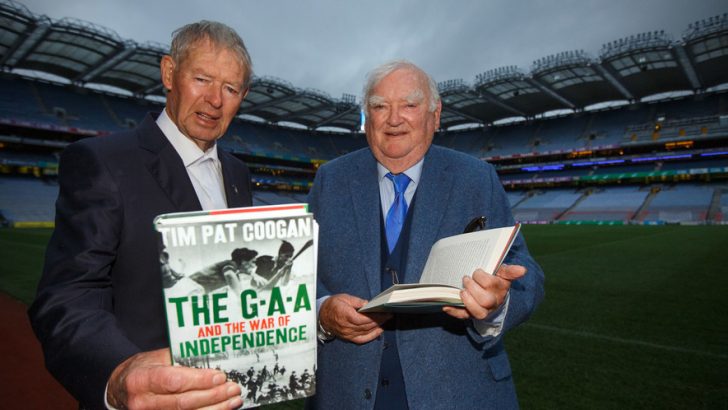

Author Tim Pat Coogan (right)

Author Tim Pat Coogan (right)