Atlas of the Irish Revolution

edited by John Crowley, Donal Ó Drisceoil, and Mike Murphy, with associate editor John Borgonovo (Cork University Press, €59.00)

Felix M. Larkin

The many plaudits this volume has received since its publication in mid-September are well justified. It is an epic production, running to almost 1,000 pages and weighing in at five kilos. Even Atlas himself would have difficulty holding it in his hands in order to read it.

The other and more general use of the word ‘atlas’ is to refer to a book of maps, and what this volume aims to do is to map the Irish revolution of 1912-23 in words and images. It comprises over 150 concise chapters, written by over 100 contributors – on subjects ranging from the 19th Century antecedents of the revolution to the contemporary public and cultural memory of it.

The chapters are supplemented by 364 original maps and over 700 other images. There is a cornucopia of information here, and this volume will accordingly be a valuable source book for the period in question for many years to come.

Its greatest virtue is its focus on the local. Tip O’Neill, the legendary Irish-American Speaker of the US House of Representative, famously said that “all politics is local”. Likewise, the Irish revolution was largely an amalgam of local efforts – not always coordinated, or directed, from Dublin.

Perspectives

As befits a volume edited by scholars based at University College Cork, this volume never loses sight of that. Its strongest section is titled ‘War of Independence: regional perspectives’ – with two chapters on Munster, one each on Leinster, Connacht and Ulster, further chapters on five individual counties, separate pieces on Dublin, Cork and Belfast, and an overview by David Fitzpatrick (whose study of County Clare in the period of the Irish revolution, published in 1977, was the model for so many other local studies).

Very occasionally, however, the local overwhelms the main story – as in the chapter by Ian Kenneally on newspapers in the War of Independence. Over one-third of this chapter is devoted to a case study of two contrasting Westmeath newspapers, the Westmeath Independent (based in Athlone) and the Westmeath Examiner (based in Mullingar).

Space

As a result, there is insufficient space for full consideration of the main national newspapers of the day – Irish Times, Irish Independent, Freeman’s Journal and Cork Examiner. The Irish Times is not even mentioned in the chapter – though the travails of Irish Times journalists John Healy and the younger R.M. Smyllie, as recounted by Mark O’Brien in his history of the newspaper published in 2008, would merit attention here. The threat to Healy’s life during the Civil War is, quite appropriately, noted in a later chapter.

For a work of reference such as this volume purports to be, the footnotes attaching to many of the chapters are perfunctory. This is a significant shortcoming: there are less than 22 pages of footnotes in total, just 2¼% of the volume’s pages. Footnotes are the indispensible apparatus of scholarship – their purpose being to cite source material, indicate relevant research by others and suggest further reading.

An omission within this reviewer’s purview relates to a Shemus cartoon reproduced in Donal Ó Drisceoil’s chapter on republican intimidation and what he calls “sledgehammer censorship” of newspapers for their support of the 1921 Treaty. Readers should have been told in a footnote that the original drawings of this and some 250 other Shemus cartoons are held in the National Library of Ireland and that the standard work on the cartoons is my Terror and Discord: the Shemus Cartoons in the Freeman’s Journal, 1920-1924, published in 2009.

Balance

Another shortcoming of the Atlas is a certain lack of balance. The editorial line is largely uncritical of the Irish revolution and of the physical force tradition of Irish nationalism. Seminal articles by F.X. Martin and Francis Shaw – dubbed elsewhere by Pádraig Ó Snodaigh as the “two godfathers of revisionism”– are, for instance, marginalised in this volume.

Even Patrick Maume’s chapter on constitutional nationalism emphasises that Parnell, Redmond and the Irish Parliamentary Party were happy to honour the physical force tradition as well as the constitutional one. True, but Maume may underestimate the extent to which this appropriation by Home Rulers of a tradition antipathetical to their values was simply an attempt to obviate the danger of being outflanked by more extreme nationalists.

The Atlas, therefore, leaves one with the feeling that all sides of the story may not have been told.

So, a qualified welcome for it: two cheers, not three. It is not the last word on the Irish revolution, but perhaps it comes close to being the second last.

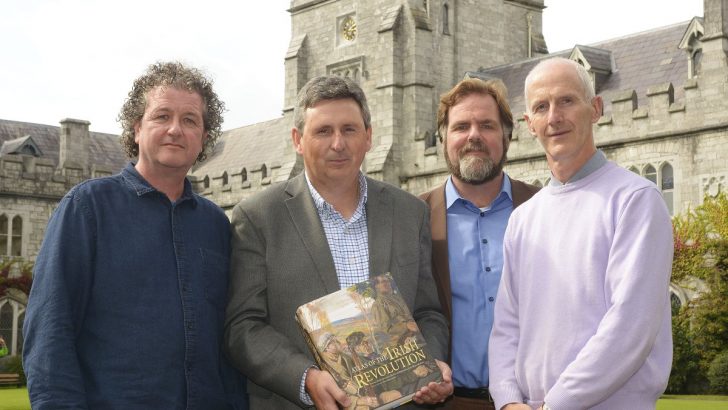

The UCC academics who created the Atlas: (left to right) Donal O' Drisceoil, John Crowley, John Borgonovo, and Mike Murphy.

The UCC academics who created the Atlas: (left to right) Donal O' Drisceoil, John Crowley, John Borgonovo, and Mike Murphy.