The Diary of Elizabeth Dillon: A Gateway to the Otherness of the Past

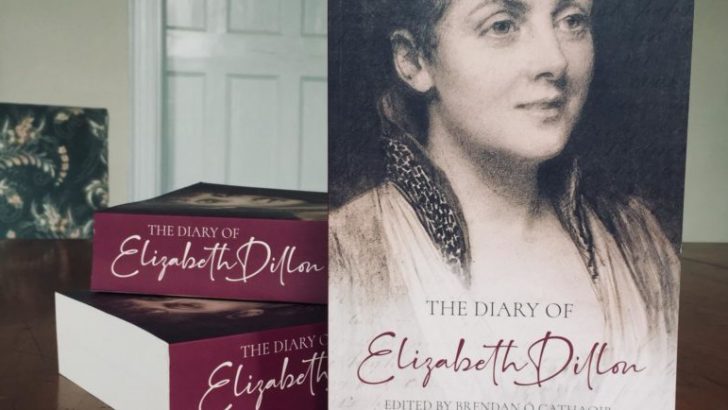

edited with an introduction by Brendan O’Cathaoir (Currach Books, €34.99)

Frank Callanan

This delightful book is considerable editorial feat. The diaries of Elizabeth Dillon are copious running to 38 journals, and have been rendered down by the editor without any loss of relevant political or social content.

The editing, and annotations, reflect consummate skill and mastery of the materials of the journals, by the late Brendan O’Cathaoir, who sadly died very shortly after the book’s publication.

Elizabeth Dillon (1865-1907) was the wife of John Dillon, a leading member of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP). Dillon was a fiery radical nationalist in his youth, and a supporter of Charles Stewart Parnell until the Parnell split of 1890-91, when he took the anti-Parnellite side.

He did so in part in the hope that he could rein in Timothy Michael Healy, who seized the initiative created by the absence from Ireland of Dillon and William O’Brien who had broken bail, until they submitted to arrest and incarceration in February 1891, to stamp the opposition to Parnell in Ireland with his own ferocity.

After Parnell’s death there ensued a grim war of attrition between Dillon and Healy on the anti-Parnellite side in which Dillon eventually prevailed but at a high price.

General election

The IPP was re-united in 1900 under the chairmanship of John Redmond. On Redmond’s death Dillon became leader of the Irish party as it faced into the rout (at least in terms of seats) of the general election of December 1918 in which he lost his Mayo East seat to Eamon de Valera.

There is a certain irony in writing a review of the diary of Elizabeth Dillon for The Irish Catholic, which throughout the 1890s was a journalistic vehicle for T. M. Healy who detested John Dillon. I myself wrote a biography of Healy which could not be considered overly- sympathetic.

O’Cathaoir makes the point that while Elizabeth is remembered chiefly as Dillon’s wife, the diary is “a testament to her own unique unfolding”. Part of that unfolding on which the diary, and editor, are very good, is the development of her relationship with John Dillon. Dillon was considered strikingly handsome, but politically rather than personally romantic.

On Redmond’s death Dillon became leader of the IPP as it faced into the rout of the general election of December 1918”

Elizabeth Mathew was born in Richmond, Surrey on March 2, 1865 and grew up in Kensington. Her father was Charles Mathew, nephew of Fr. Theobald Mathew, born in Lehenagh outside Cork, went to Trinity and the King’s Inns and was called to the English bar in 1854, and was made a judge of the Queen’s Bench in 1881. Elizabeth mysteriously referred to her distinguished father as ‘Monsieur’.

She was a highly-educated and widely-read Catholic lady, her philosophy “a blend of the assertive Catholicism of the age, her English liberal heritage, and the Irish nationalist aspirations of the Home Rule movement”. She combined daily attendance at Mass with philanthropic activities and dallied in the House of Commons.

She met Dillon in October 1886, when she was 21 years old: “Well, he is the first person who has awed me.” Their romance was slow of inception, but they married on November 4, 1895. Theirs was an exceptionally happy and fruitful marriage, but it was cut short by her early death at 42 on May 14, 1907, leaving Dillon disconsolate.

The political perceptions and judgements set down in the diary for the period of her relations with Dillon almost invariably track his. Part of the historical interest of her account of her husband’s political life lies in the portrayal of Dillon’s selflessness, a negation of Healy’s view of Dillon as a figure of morose ambition. Her views were frequently exorbitantly if unsurprisingly bourgeois, notably in her dismissal of the poets W. B. Yeats and Lionel Johnson.

Historically, however, such insights are one of the merits of the diary of Elizabeth Dillon as splendidly edited by Brendan O’Cathaoir.

Frank Callanan SC is the author of Tim Healy (Cork University Press, 1996).