There was a time – it encompassed most of the 1980s – that Catholic publishers weren’t very interested in what the largely unknown Fr Joseph Ratzinger of Germany had to say about Christian morality, the mystery of the heart of Christ, the role of religion in post-Marxist Europe or, for that matter, any other topic.

US Jesuit Fr Joseph Fessio was an exception. The California priest had already become convinced of the highly academic German priest’s ability to synthesise Christian truth and complex theological issues and express them succinctly, as well as in a way that encouraged deep reflection and meditation.

By intention and providential design, Ignatius Press, established by Fr Fessio in 1978, became the sole English-language publisher of the pre-papal books and the biography of the man who was elected Pope Benedict XVI in 2005.

“We knew we wanted to publish translations of fine European theologians like Ratzinger, Henri de Lubac, Hans Urs von Balthasar and others,” Fr Fessio told Catholic News Service before the retired pope’s death December 31. “It was kind of a golden age of Catholic theology, in the mid-20th century. But their works were rarely translated into English. That was our mission.”

Pope Benedict’s body of writings will be his legacy, said Fr Fessio. Ignatius Press pledges to keep his core writings in print.

“He will be not only a saint but a doctor of the church someday,” Fr Fessio predicted.

Fr Fessio gained a deep-seated admiration of Fr Ratzinger in the early 1970s, while pursuing a doctorate in theology at the University of Regensburg, in what was then West Germany. His thesis, “The Ecclesiology of Hans Urs von Balthasar,” was directed by Fr Ratzinger, his professor and mentor.

During that process, he also gleaned an appreciation of his mentor’s great intelligence.

“We had these seminars with theological and doctoral students – maybe seven or eight of us – and he’d be directing the seminar. They’d last about two hours, and he’d make sure everyone had his chance to speak. He would ask people what they thought about this or that, and at the end, he would sum up the whole seminar in just a few very long, German sentences. He had a tremendous power of synthesis. He listened so well. He grasped things immediately, and he organised them very organically,” said Fr Fessio.

The Jesuit said that later, when then-Cardinal Ratzinger oversaw the writing of the “Catechism of the Catholic Church,” he saw the same qualities.

“He had the tremendous ability to understand what others were saying and writing,” Fr Fessio added. “He could be critical, but he was fair, and then he would present what he thought was a more accurate view of things.

“He really had a serene and humble insight. He was such a great person and had a great mind.”

After graduation, Fr Fessio began to participate in the annual three-day-long reunions of his mentor’s Schulerkreis, or group of former students. Fr Ratzinger, meanwhile, was named the archbishop of Munich and Freising, and soon afterward, a cardinal.

In 1989, under Cardinal Ratzinger’s tutelage, Fr Fessio and three others were instrumental in forming a house in Rome called Casa Balthasar – a place of discernment for young men and women. The house took its inspiration from the life and works of Adrienne von Speyr and two highly regarded theologians: Jesuit Fr Lubac, whom St John Paul elevated to cardinal in 1983, and Fr von Balthasar, named a cardinal by St John Paul II in 1988.

At the time Casa Balthasar was established, Cardinal Ratzinger had been appointed prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith by St John Paul II. He became cardinal-protector of the home and remained involved with Casa Balthasar into the beginning of his papacy.

Pope Benedict’s capacity to understand, summarise and evaluate extended beyond the great theological discussions for which is he was known, said Fr Fessio. “It was philosophy, literature, history, art, music – all these things that make up the so-called humanities. He was immersed in and interested in all these things.”

“He had a warm and wonderful sense of humour. It would come up all the time,” Fr Fessio added. “He would grasp the irony of things.”

When members of the Schulerkreis would gather with him to pray, celebrate Mass and share meals and engage in discussion, not all the discussions were of an ecclesial nature. But Pope Benedict could speak to them all.

“He was a great listener and conversationalist, always with a warm sense of humour. He has done all things well. He was a wonderful orator and speaker, preacher, writer and thinker.”

Fr Fessio also said the late pope’s great love for the Church was always evident.

“His insistence on the continuity of the Church before and after Vatican Council – that was an important part of his papacy. In fact, he emphasised that in the very first talk he gave when he was made pope. He was elected around 6:30 at night, and the next morning at 9:30 he gave a talk in Latin, which he himself wrote without any help, and he made it very clear that he was a pope of the council – but that we had to see the council not as a rupture from previous church teaching, but rather in continuity with it.”

CNS.

Ruadhán Jones

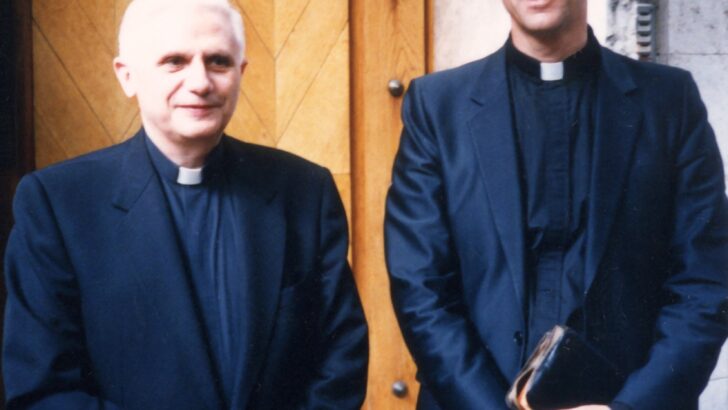

Ruadhán Jones Jesuit Fr Joseph Fessio is pictured with then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger in this 1987 photo. Fr Fessio is the founder of Ignatius Press, a publisher of the late Pope Benedict XVI's books. Photo: CNS photo/Dorothy Peterson, courtesy Ignatius Press

Jesuit Fr Joseph Fessio is pictured with then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger in this 1987 photo. Fr Fessio is the founder of Ignatius Press, a publisher of the late Pope Benedict XVI's books. Photo: CNS photo/Dorothy Peterson, courtesy Ignatius Press