The View

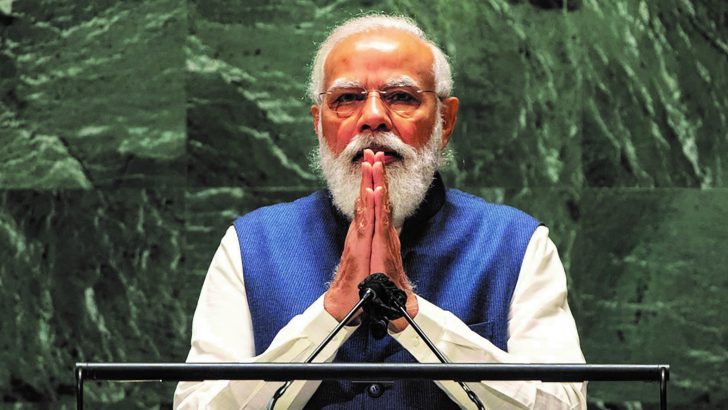

A friend, who has long been involved with the ecumenical outreach of Clonard Monastery in Belfast, wrote to me recently about the concerns that many of his Indian friends had about the direction of their country under Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his attempts to establish for it a dominant Hindu ethos and identity, accentuating the marginalisation of other groups.

It is difficult and often unwise to form definite judgments about what is happening in other societies without detailed first-hand knowledge of them. But it was a reminder of the wise statement in the 1993 Downing Street Declaration with John Major, where then Taoiseach Albert Reynolds, on behalf of the Irish Government, considered “that the lessons of Irish history, and especially of Northern Ireland, show that stability and well-being will not be found under any political system which is refused allegiance or rejected on grounds of identity by a significant minority of those governed by it”. Obviously, this referred both to Northern Ireland under the old Stormont, but also to a future united Ireland lacking the consent or acquiescence of the unionist community. This is not an argument to forestall valid democratic decision-making, but rather an injunction not to repeat the mistakes of the past. Any future united Ireland should be based not on a majority/ minority ‘two-nations’ style approach, but on a re-balanced, inclusive and pluralist identity to match a new polity. As Brendan O’ Leary has observed, the way PR operates ensures that every political force in the island is likely to be in a minority, and unable to exercise an oppressive majority rule.

Agreed

One point on which historians are agreed about partition is that Ulster Unionists obtained what they wanted, the maximum area of population that they could control incorporated into Northern Ireland. Fellow Covenanters in the three ‘southern’ Ulster counties assigned to the Irish Free State were informed, in an unfortunate analogy with the Titanic, that there were not enough lifeboats to go round.

Is this judgment right? Viewed from a centenary perspective, Unionists enjoyed close to 50 years, when they were in control, with minimal oversight from Westminster. The IRA border campaign of 1956-62 was easily defeated. However, a minority of 35% was by any international standards a very large one to keep out in the cold, even if post-war the advent of the British welfare state improved everyone’s situation with regard to health, welfare and education.

Democracy is often defined as majority rule. It has long been recognised that, where community differences are so deep that majorities and minorities are frozen instead of fluctuating and changing places, democracy cannot properly function. Two examples set boundaries to the discussion, Northern Ireland and South Africa. What had been the ruling white minority constituted less than 10% of the population. In the Irish Free State, later the Republic, the minority, whether defined as ex-unionist or Protestant, was likewise below 10%. After upheavals subsided, both were protected to a degree by the wealth and assets they were able to bring to a new State. Even though this position in many cases reflected previous inequality, injustice and worse, pragmatic considerations and concerns for the welfare of the greatest number meant that previous élites who wished and were able to stay, where conditions permitted, needed to be accommodated in the new dispensation as well as having to adjust to it. Treating them as the Soviet Union did the tsarist elite in its first two decades as ‘former people’ or worse would have been ruinously costly as well as politically destabilising. Independent Ireland survived, when many other contemporary new states that pursued more radical courses did not.

Power

When they have lost power without any prospect of reversal, small better-off minorities tend to be more concerned about protecting their material situation rather than involvement in a politics with which they do not identify or futilely combating changes designed to reflect the culture, identity and aspirations of a newly empowered majority. There is little basis for the prevalent notion today that social conservatism or liberalism in Ireland is much determined by reference to religious denomination.

It would be good, however, if there were less stereotyping, particularly the notion that the Protestant minority remained nostalgically backward-looking, instead of contributing to life in their own sphere of activity and thereby to nation-building. In contrast, the geographically concentrated unionist community has a critical mass that has to be convincingly accommodated.

South Africa under majority rule has not experienced a change of government, but nonetheless in the Mandela years described itself as ‘a rainbow nation’. Of course, there are minorities there which are not white, notably the Indian and coloured communities. Trinity College lecturer Dr Kader Asmal, leading light in the Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement, of Indian background went back to South Africa after 1990, and was for many years an energetic government minister in vital departments such as water and education.

Hindsight

With hindsight, it is better for all concerned that in Ireland the principle of separation of Church and State was maintained after independence, even if for some time the separation in many areas was minimal. The idea was mooted, but not pursued, that the Church should have a veto over legislation. In countries, like Iran and Afghanistan, supreme power belongs to a religious leader, whether Emir, Caliph or Ayatollah. It does not make for tolerance or pluralism, and running a state, including feeding and educating a people, requires more qualifications than knowledge of religious law.

Undeniably, great statesmen in the past have come from the ranks of the clergy. One has only to think of Cardinals Wolsey, Richelieu, Mazarin, Fleury and Alberoni, to name but a few, not to mention the apostate çi-devant Bishop of Autun, Talleyrand, Foreign Minister of Napoleon and Louis XVIII, but mostly raison d’état was the governing principle. Rev. Ian Paisley finally broke with fundamentalism by leading his party into coalition with Sinn Féin, becoming First Minister. However, the founder of Christianity said: ‘My kingdom is not of this world’.

India’s Prime Minister

Narendra Modi

India’s Prime Minister

Narendra Modi