Mainly About Books

by the Books Editor

The slogan ‘Black Lives Matter’ has rightly swept the world, but we can’t lose sight of the fact that it protests about the condition of racial harmony – or lack of it – in the United States today.

Like so many movements of the moment, it reflects an often hazy ideas about the history of slavery. Americans often see the world through their experiences only. But recent black American experience is part of a long and complex history of slavery and of attitudes to black cultures.

They are willing to discuss the old South and the North Atlantic slave trade – these are relevant to their history. But they rarely reflect on the history of the West Indies, of the contrasts between say Jamaica and Haiti (though a new life of Toussaint L’Ouventure has just appeared).

Little is heard of Brazil, where a culture of black slavery by Portuguese royalty and rich fidalgos [sic] was thought acceptable to Catholic theologians down to the 1950s, slavery itself having been abolished only in 1888.

Nor indeed the special history of Liberia, where local African cultures were colonised by former American slaves with European names, planted there by American resettlement societies, who became a class of black ‘colonialists’, an elite who still run the state.

By avoiding slavery the author avoids addressing the real role of Arab culture in West Africa. It was not an equal partnership”

These confusions of history are well illustrated in an article in the current National Geographic History. Written by content provider Mariá José Noain it is entitled ‘Kilwa, City of Coral and Gold’. It would have been truer to history to have called it ‘City of Gold, Ivory and Slaves’.

This deals, with interesting photographs, with the narrow Swahili strip along the east coast of Africa and the medieval Arab settlement of Kilwa.

On the first page a timeline box remarks: “1840s. Dwindling trade leads to the abandonment of Kilwa, once rich medieval sultanate on the Swahili coast.”

That phrase ‘trade’ had since the 7th Century been largely one based on slave trafficking by Arabs, the ancestors of those who now rule the Arabian states.

Abu Dhabi, so beloved by shoppers, is today a city built on oil by a culture founded on slavery.

The ‘trade’ along the Swahili Coast declined because of the British navy’s efforts to suppress the slave trade at source.

The theme of Noain’s article is that the Swahili Coast was a sort of African El Andalus, where Muslim culture and African life flourished in harmony for the good of both sides for centuries. But she misrepresents what happened.

There are references to gold and ivory, but not to how these were gathered over the centuries by caravans that ruthlessly penetrated the interior. Arab culture left no mark on the interior, bar Islam.

By avoiding slavery the author avoids addressing the real role of Arab culture in West Africa. It was not an equal partnership.

When the British took over what is now Kenya for white settlement, the interior became a ‘colony’. The strip along the coast became a ‘protectorate’, by which the British acknowledged the independent sovereignty the Sultan of Zanzibar, a scion of the Royal family of Oman.

It only came under African rule in 1960, after 14 centuries of Arab domination, begun long before Europeans came on the scene.

No secret

Now none of this is a secret. It can be read about in Victorian books by Dr. Livingstone, Richard Burton and many others. But I have never ever read of any suggestion that the Arab States, including Saudi Arabia, be asked to apologise for the crimes of the Arab slave trade (which was entirely under Arab and Ottoman control), and pay suitable indemnities to the cultures they marauded for so long.

There was one particularly horrible aspect of the Arab slave trade. Proud black men torn from their villages in the interior arrived in the Ottoman Empire as ‘negro eunuchs’ with no manhood…but the details of this are not for a family newspaper. Across the Ottoman empire old slaves could only be replaced by fresh slaves. This trade continues today. Yet for black Americans, no blame seems to attach to Arab cultures.

Yes, ‘Black Lives Matter’. But they matter everywhere, and that includes East Africa.

Peter Costello

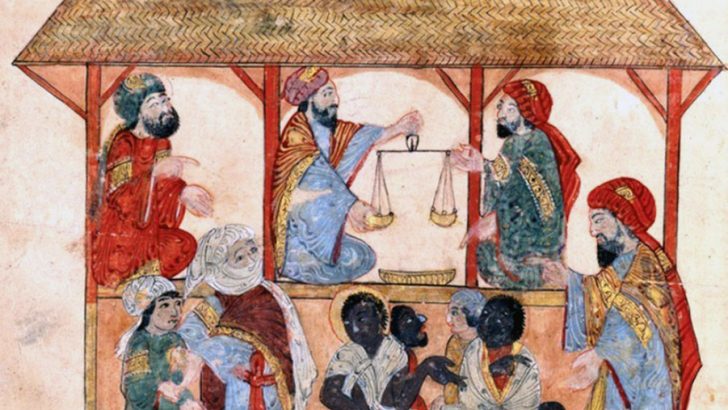

Peter Costello An Arabic image from the 1200s of Arab slave traders at work.

An Arabic image from the 1200s of Arab slave traders at work.