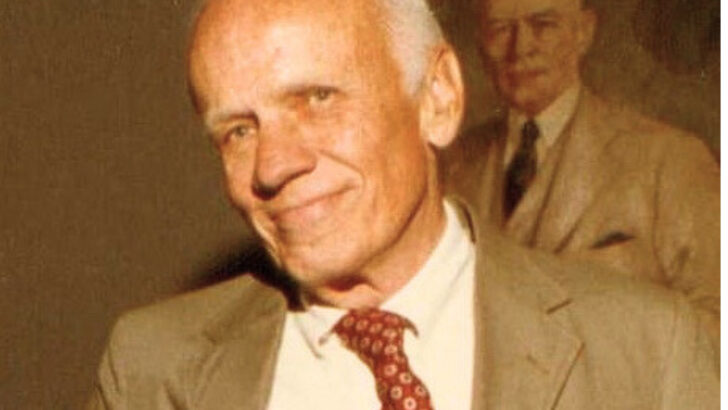

Scott P. Richert

We… see all round us every day the living turning into the lifeless. What we never see is the lifeless turning into the living,” said Owen Barfield.

When I was a child, I used to collect common fossils – trilobites, brachiopods and cephalopods, mostly. I was fascinated by their shape and symmetry, which seemed to me almost mathematical in structure. Finding fossils was so easy in part because every fossil of each species looked pretty much the same. Stripped of everything that may have made this trilobite different from that one, each fossil was distilled down to its essence.

Or so it seemed to me when I was young. Perhaps the main reason I quit collecting fossils as I grew older is that, if you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all. Their lifeless, essentially mathematical unity was fascinating for a short while, but there’s something far more fascinating about the diversity of living things, even of the same species.

The temporal end of every man may be his skeleton, stripped of flesh and awaiting the Second Coming in the grave, but outside of a few of the most obstinate and obnoxious atheists, no one would say that the skeleton is, or even represents, the essence of man. His actions, his words, the twinkle in his eye as he tells a joke, the vacant stare in that same eye as he mourns the loss of his wife: All of these things that remain in our memory when he has gone to his grave are closer to his essence than his skeleton is. And when we remember him after his passing, it is those things, and not his skeleton, that spark our imagination and bring him back to life, however briefly, for us.

True

What is true of the trilobite and of man is true of our language as well. What makes a word or a phrase tickle our ear or “pop” in our mind is not the collection of letters on a page – the skeleton of the word, so to speak – and certainly not its repetition, which is as likely to turn a living word into a lifeless one as picking up his hundredth trilobite fossil is to turn a young man’s mind to different pursuits. Rather, the essence of a word, what excites our imagination, is its meaning.

But as Owen Barfield, the last of the Inklings (the literary group at Oxford University in the 1930s and 1940s, of which J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis are the best-known members), and Walker Percy, the Catholic novelist, psychologist and amateur linguist, both demonstrated – Barfield, in his essays; Percy, mostly in his novels – the entire thrust of the modern world is to deprive words of their meaning, to turn the living into the lifeless. Stripped of their essence, words become fossils.

Destruction

This destruction wrought by the modern world has theological implications, because Christ, St John the Evangelist tells us, is the ultimate Word, the fullness of Truth, who gives every other word its meaning and its life.

In his novel The Thanatos Syndrome, Percy (through the character of a priest) posits that, if words have been deprived of their meaning, there must be a Depriver, one whose entire purpose is to prevent man from finding meaning in life, to leave him stranded in a fossilised world, to gut his imagination so that he may repeat the words “Do this in memory of me” and yet never truly call to mind and enter into the living reality of Christ at the Last Supper, Christ on the Cross, Christ risen again on the third day.

All around us, the living turns into the lifeless, and only God can breathe life into that which is not living. Only God… and man, to the extent that we take part through grace in the life of God, participate in the Word as members of the Body of Christ, and let the Holy Spirit kindle in us the fire of our imagination, returning meaning to a world that has been deprived of it.

Scott P. Richert is publisher for OSV.