Recently congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene, US representative in Washington for Georgia’s 14 congressional district, a lady deep sunk in controversies of all kinds, raised a few more eye-brows by her reference to the “Anglo-Saxon heritage” on which “these United States” are raised.

She is, of course, one of those who have in any case little interest or respect for the numerous cultures that in effect created the modern United States – here we might well imagine that her Irish-America constituents might have a more nuanced view of the culture of Elizabethan and Jacobean England to which she was seemingly alluding. (That is if she could actually define what she meant in any case by the term.)

Pilgrim Fathers

But the general claim is that the United States owes its cultural origins to the Pilgrim Fathers. They after all were strong-minded and belligerent folk whom England had exiled because they would not settle down as good neighbours. In the popular memory of the United States they are regarded as intolerant witch burners, which are not attractive attitudes for citizenship in a complex community. Their freedom was maintained by restricting that of others. (The Puritan ideal was more complex than this, but in the heat of controversy what one’s political enemies believes quickly becomes distorted.)

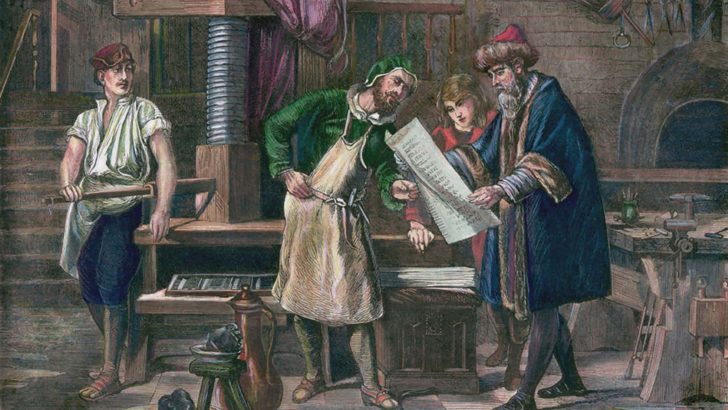

The printed book is generally regarded as one of the critical steps in the creation of modern society, but it has not been without controversy.

The heirs of the Pilgrim Fathers used to claim that the first printing press in America, indeed in the Americas, was that set up in New England in 1639. Indeed the first book ever struck off in the New World was an Almanac, owned, edited and distributed by William Pierce, of Cambridge, Mass. Later Mr Pierce put out a metrical version of the Bible.

However, it was established in 1908 by a Dominican scholar, Fr. V.F. O’Daniel, that the first printing press on what is now US territory was set up by a Mr Glover, at Cambridge, Mass., certainly and in 1639. The first item printed was the Freeman’s Oath, which made the Pilgrim Father’s book the second.

But the simple claim that these presses were the first in the New World is mistaken. As early as 1536 – a mere 80 odd years since it was introduced by Johann Gutenberg – there was a press in the city of Mexico, as Fr O’Daniel explained in the typical combative style of nineteenth century religious controversy:

“There is the proud capital of the great empire of the Aztecs, whose powerful and haughty sovereigns had for centuries lorded over the surrounding nations, had offered hecatomb upon hecatomb of human victims to their idols, the white robed sons of St Dominic published The Spiritual Ladder of St John in the year of Our Lord 1536 more than 100 years before the Pilgrims published their first works at Cambridge, Mass. The book was of a religious character, while that of the Puritans was only an almanac”.

I don’t suppose, however, that a Dominican scholar of today would express his views of the facts in quite such a combative style today. (The work printed in mexico, usually known as The Ladder of Divine Ascent, composed about 600 AD by St John Climacus of Sinai, could not have been more Catholic.)

So the printed literary culture of the Americas, in Spanish, Portuguese, French, Dutch, Swedish. and of course, English, owes its initiation to the culture of Latin Europe. According to H. L. Mencken in the 4th edition of The American Language (p. 682, aside from contributions from African cultures, a little Gaelic from Irish emigrants got in there too.

Crowds

This linguistic carnival rather crowds in on the simple Anglo-Saxon culture seeming so all-encompassing in the view of Congresswoman Greene.

How sad for those with simple supremacist agendas, that the actual facts of history are so contrary, so complex, so open to constant revision. For the history of every country, not only in the Americas, but in Europe as well, is a process of constant, and necessary, revision; a process, too, of increased understanding.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello An early press at work

An early press at work