A sense of history is needed to talk sensibly about God, a leading ecumenist tells Martin O’Brien

Dr Johnston McMaster, ecumenist intellectual, teacher and advocate of “public theology”, author and Methodist minister, one-time youngest soccer player in the Irish League at 15, chooses his words carefully but there’s no mistaking his disappointment at where the North is 20 years on from that historic Good Friday of 1998.

“A lot has been achieved and there is still a lot to do. But, the promise of the Belfast Agreement has not been fulfilled. It was not a peace agreement but a template for a peace process and that means we’re really talking about an inter-generational process.

“I once thought this would take a generation, 25 years, but I think it will be closer to 50 years.

“I suspect that not unlike Germany post-War, there will be a skipping of a generation, the emergence of a generation still in their buggies, that have no memory of the Troubles, who will interrogate our past and begin to ask awkward, uncomfortable questions, especially of parents and grandparents.”

McMaster (71), who hails from Portavogie, a mainly Protestant fishing village on Co. Down’s Ards Peninsula, is author of many highly regarded books and pamphlets on themes including peacebuilding, Celtic Christianity and social ethics.

Reconciliation

For 17 years from 1997, as a full-time lecturer in the Irish School of Ecumenics he helped run a mainly EU-funded “community education for reconciliation programme” that attracted up to 2,000 adult participants a year from Northern Ireland and the Republic’s border counties, in local centres, to explore a host of issues including hate, violence, sectarianism, restorative justice and human rights.

“It was a dream programme – in a sense my career to that point with its focus on an inter-disciplinary approach to theology embracing the historical and the political was a preparation for it.”

*****

He also takes pride and in having helped to organise and contribute to a programme marking the Decade of Centenaries that over a four-year period has attracted 20,000 people to numerous lectures, conferences and seminars.

“The willingness of so many people to engage in that way is a hopeful sign, in contrast to the political paralysis and all the polarisation caused by Brexit.”

McMaster, an impressive broadcaster of religious reflections for the BBC, recalls that in 2000 he suffered a heart attack while broadcasting Thought for the Day live on BBC Radio 4 from a studio in Belfast.

“I thought my quite severe chest pains were indigestion but somehow I drove home and ended up in hospital for a triple by-pass.”

Brought up in a strong Methodist family, his preparation for the role of prominent ecumenist intellectual began early.

“My first ecumenical encounter was at the age of five when my mother approved my admission to the Mater Hospital (in Belfast) to treat acute adenoid problems. I have never forgotten that experience, the nuns, the Catholic symbols, the Rosary beads.”

He met a Catholic for the first time as a 17-year-old, befriending a workmate in Belfast while training to become a radio officer for the Merchant Navy, before, influenced by his Methodist minister uncle he began training for ministry.

“I discovered that that young man didn’t have horns; he was a human being and a person of faith and I think that experience encouraged my ecumenical approach to life.”

His fisherman father was an Orangeman but attended the funerals of Catholic friends “and his anti-sectarianism and sense of justice left an impression”. However, the Orange Order was not to McMaster’s taste and he never joined. His mother, the more intellectual parent, encouraged him to ask questions.

Impression

As a 10-year-old he recalls being glued to the radio news bulletins about the Hungarian Uprising and the Suez Crisis of 1956 and discussing these with his mother.

“She always left the impression that whatever the issue there are more questions to be asked. Hopefully, I have been asking questions ever since.”

Young Johnston found himself asking profound questions of himself during a two-year “dark period” from the age of 16 when “exposed to the mild religious fundamentalism” of his parents and fellow parishioners who “read the Bible literally”. He embarked on “an emotional and intellectual journey during which I asked: ‘do I have faith at all?’” But he came out of that becoming a trainee minister in the Methodist Church’s Edgehill Theological College in south Belfast, being ordained in 1974.

However, his passion for soccer and prowess as a goalkeeper could have resulted in a different career, inspired by his three heroes, the great world class keepers, Yugoslavia’s Vladimir Beara, the Soviet Union’s Lev Yashin and Harry Gregg of Northern Ireland and Manchester United.For several years he was the youngest player in the Irish League, playing for Cliftonville and then Distillery, and at 16 he was devastated when his parents and college principal decided he was too young to accept an offer to join then English Division 2 club Scunthorpe United. “It took me quite a while to get over that but by the time I did another vocation was beckoning.”

Having never been further south than Dublin, he experienced “a huge culture shock” when at 25 he was posted to Dunmanway in West Cork as a probationer minister in 1971.

*****

McMaster’s stay there, until 1975, changed his life for ever, resulting in his twin pursuits of Irish history and the Celtic tradition, the latter crystallised in a nearby place he fell in love with, Gougane Barra, where St Finbar is believed to have founded a monastery, “one of the most peaceful and beautiful places anywhere”.

In Dunmanway Methodist church graveyard he discovered a headstone to one of the Protestants killed in the Bandon Valley Massacre of 1922 and suddenly became angry he had not been taught any Irish history.

“I went out to raid the bookshops of Cork and I think I have been pursuing Irish history ever since. How can you talk about God in a meaningful way if you have no historical context?”

That link he sees between history and theology impelled him to undertake his doctorate in ministry from Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary in Illinois that examined Methodist stewardship in Irish politics between the first Home Rule Bill (1886) and the Anglo-Irish Agreement (1985).

After a decade in the Republic McMaster returned North in 1980 to minister in strife-torn north Belfast.

In 1984 he was appointed head of the Irish Methodist Church’s youth department, a post he held until 1992 when he co-founded Youth-Link, the inter-church youth agency which still thrives today.

McMaster, who recently conducted a programme on public theology at Drumalis, Co. Antrim, is critical of all Churches for “their failure to produce a theology of non-violence”.

During the Troubles he acknowledges some valuable inter-Church documents were produced but “the Churches were strong on condemnation and weak on analysis”.

He espouses “a fairly radical hermeneutical shift from individualism to a social, political reading of the [Biblical] texts” leading to the growth of “a public theology focussing on what we do in the public square, on values and ethics”.

“We need social reconciliation, political reconciliation, community reconciliation”.

Dr McMaster appears to be saying that the heart of the problem facing the churches in their quest for relevance in a post conflict situation is one of hermeneutics or interpretation in relation to the Bible.

“The churches have a real difficulty in developing a meaningful theology of social reconciliation arising from their very vertical sense of reconciliation, between the individual and God, and if there is a horizontal dimension at all it is between individuals, at person-to-person level, but there appears to be an inability to develop social, inter-community reconciliation.”

Given our historical divisions in this island and post conflict problems in the North many might concur that Dr McMaster’s is an idea whose time has come.

Martin O'Brien

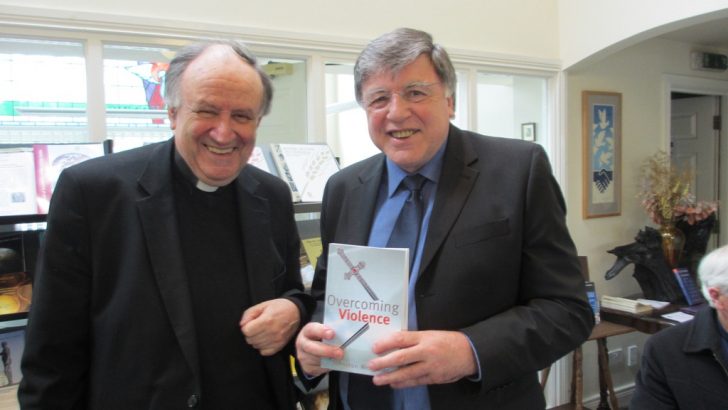

Martin O'Brien Johnston McMaster with Bishop Anthony Farquahar at the launch of his book Overcoming Violence

Johnston McMaster with Bishop Anthony Farquahar at the launch of his book Overcoming Violence