The Catholic Reformation entailed coercion as well as wide-ranging reform projects, writes Tadhg Ó hAnnracháin

Few terms in historical writing have attracted more dissatisfaction than ‘the Counter-Reformation’. Among the more recent attempts to formulate an alternative are ‘Catholic Reformation’, ‘Catholic Renewal’ or the broad catch-all of ‘Early Modern Catholicism’.

Each of these designations depart from the conviction that the changes which occurred in 16th- and 17th-Century Catholicism were not simply reactions to the emergence of various forms of Protestantism in the wake of Martin Luther’s break with Rome. Rather, they represented something more profound, of a much longer duration and not confined to Europe, which cannot be considered as merely reactive.

The term ‘Catholic Reformation’, for instance, builds on the insights of German historiography, in particular, that similar developments occurred both in that portion of the continent which remained in communion with Rome and in Protestant Europe, so that in many respects 17th-Century Catholicism came to resemble its reformed counterparts more than it did its medieval ancestor.

Yet the term ‘Counter-Reformation’ continues to hold considerable currency among non-specialists and it has the indisputable merit of focusing attention on the massive stimulus which the fracturing of European Christendom gave to the Roman Church in its future development.

Evolution

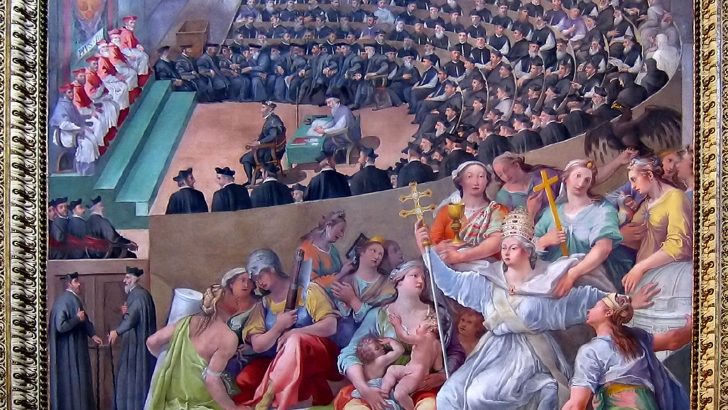

The ‘Holy Trinity’ of the historiography of the Counter-Reformation are the Council of Trent, the rise of new religious orders – most notably the Jesuits, and the reforming Popes. All were indisputably important in the evolution of Early Modern Catholicism.

The Council of Trent was of course neither the first nor the last major ecumenical council of the Church but the interpretation of its decrees was to be profoundly influential. The emphasis here is consciously on the interpretation because, to a significant degree, what was decided at Trent was less important than what Trent was believed to represent- some of its decrees were observed much more than others.

Many of those present at the council saw it as something approaching a failure and it was actually the subsequent generation which helped to create the legend of the council as a decisive moment and as a definitive formulation of Catholicism. In this regard, the work of the late 16th-Century Jesuit theologian, Robert Bellarmine, was of great significance. His Disputationes de Controversiis Christianae Fidei Adversus Hujus Temporis Haereticos (Arguments against the heretics of the current time about the controversies of the Christian Faith) provided a detailed working-out of the theological positions articulated at Trent and an exhaustive defence of their legitimacy that helped to create an enormous sense of intellectual confidence within Catholicism.

Bellarmine’s work contributed to a sense among Catholics that their Protestant opponents had been put on the defensive, and to some extent they were correct. Trent, which closed in 1563, is generally credited with two principal accomplishments: in its doctrinal decrees it drew a clear line between an official Catholic position – including a defence of the traditional Latin Bible (Vulgate text) as free from significant error, the interpretative role of the Church, seven Sacraments, the intercession of saints and the role of works in salvation – and that of the Protestant reformers.

The council was dominated by Spanish and Italian representatives and one of the effects was to confirm that there was to be no possibility of accommodation with the different theological positions which had been consolidated north of the Alps over the previous decades. It thus protected central aspects of the traditional doctrine which had developed in the Latin Church over centuries, although at the expense of closing the door on the possibility of compromise and agreement with ideas which were now pronounced as anathema and deadly heresy.

Quality

In tandem with this, Trent articulated a vision of pastoral reform which aimed above all at improving the quality of the clergy in terms of their education, their personal life and their residence and activity in their ministry, with the expectation that this would have dramatic effects on the lives, morals, and chances of salvation of those within their spiritual care.

Those who enjoyed the fruits of a benefice, such as a parish, were now expected to discharge its duties or at the very minimum to use the revenues to ensure that those dependent upon it for ministry received their due from a substitute. In many respects this represented merely a re-articulation of received wisdom and it was only slowly and unevenly adopted but the long-term effects were profound.

The Jesuits, ironically, were not originally conceived as a teaching order although this arguably the area in which they were to make their greatest contribution. By the second decade of the 17th Century, Jesuit numbers stood at over 13,000 personnel (a close to four-fold increase on the situation in 1563 when the Council of Trent actually closed) and they boasted 400 colleges and a common mode of teaching which was to prove hugely influential in the formation of the Catholic elite, both secular and lay.

But neither in its distinctive spirituality, which had clear roots in medieval Catholicism, nor in its organisation, which was heavily influenced by Ignatius Loyola’s personal background, was the Society of Jesus simply a reaction to the Reformation even if it was fated to become the bogeyman of the European Protestant imagination. The common emphasis on the Jesuits tends to ignore the vital importance, frequently exceeding that of the Society, which other religious orders continued to have, in particular the families of friars such as the Franciscans and Dominicans.

In terms of the reforming Popes, arguably one of the most important changes of the Early Modern period was the manner in which the papacy became an advocate and champion of reform rather than its greatest opponent. Among the reasons why an ecumenical council of the Church did not meet until 1545 was the fear in Rome that it would actually intensify the attack on papal power. In the event, the papacy assumed authority over the council’s legacy and interpretation and used this to intensify the monarchical character of the Church’s leadership.

But this line of reform certainly did not stop with the eccentric Franciscan Pope, Sixtus V (1585-90). His successors continued to see patronisation of the implementation of what they saw as the core of Tridentine legacy as a key aspect of their function.

*****

At the beginning of the 1560s, European Catholicism was in notable disarray. Trent had been stalled since 1552. In Germany the Peace of Augsburg (1555) had confirmed that the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, was unable to re-impose Catholicism in northern Germany which also opened the way to the consolidation of Lutheranism in Scandinavia. In Poland, state support for Church sentences of excommunication had been withdrawn creating a platform for Protestant growth.

Even in Habsburg dominions, different strands of reformed belief were spreading like wildfire so that Catholicism was being reduced to minority status in Austria, Royal Hungary and Bohemia. Elizabeth I’s accession in England in 1558 opened the way to the loss of Britain, and apparently Ireland.

The number of Huguenots was mushrooming in France and in 1559 the sudden death of King Henri II initiated decades of political chaos which allowed the Protestant party to grow further in strength and create a formidable military capacity. In the Netherlands, Philip II’s attempts to reinvigorate the Catholic Church to better repress the spread of Protestantism was on the throes of igniting an eighty year conflict which created a Calvinist-dominated Dutch republic.

Throughout, the menace of the Ottoman empire, which had swallowed important Catholic outposts such as Albania and the Kingdom of Bosnia in the preceding centuries, continued to grow, cementing its position in central Hungary while its naval power threatened the entire southern flank of European Catholicism (yet effectively posing little or no danger to the Protestant north).

Only in the Italian and Iberian peninsulas, both politically dominated by Spain, could the Roman Church be seen as safe from an internal Protestant challenge and the possibility seemed to threaten that Catholicism might be reduced to simply the religion of the Spanish crown.

The next three-quarters of a century, however, were to witness a dramatic recovery and this can be seen as the central period of Counter-Reformation. Much of it was saturated in violence. In Ireland, it was the state-building wars of the late Tudors which so alienated the population that they rejected Elizabeth’s Church. In most of the continent though, violence and repression were to be among the Catholic weapons of choice although, of course, it was not merely the Church of Rome which practiced religious war.

The whole might of the Spanish empire was poured against the Dutch resulting in the end in the partition of the Netherlands into the Spanish-retained Catholic south (eventually Belgium) and the Dutch Republic. Ironically, at the beginning of the conflict, the north had actually been the area with fewest Protestants.

Claim to the throne

Decades of often vicious internal war in France were finally resolved when the leader of the Huguenot party, Henri of Navarre, who had the strongest claim to the throne, abjured Protestantism. Crucially, Pope Clement VIII resisted Spanish pressure and accepted his reconciliation with the Church.

This paved the way for European Catholicism to be rebalanced between two great royal families, the Bourbons of France and the Habsburgs. From the 1590s, the Habsburgs began a policy of forcible re-Catholicisation in Austria in which Emperor Ferdinand II played a leading role. Following the military conquest of Bohemia in 1619, the same policies were introduced there. Those who refused to conform to Catholicism were forced to sell over their property and go into exile, as tens of thousands did. Converts, on the other hand, were treated very generously.

In Hungary (which included much of modern-day Croatia and Slovakia), because of the Turkish threat the dynasty could not be so severe but instituted a successful policy of blandishment which inspired many conversions and recreated the framework of a Catholic kingdom.

Important Aspect

Similarly, in Poland, the position of the Roman Church strengthened steadily without overt persecution of Protestants but as the kingdom faced threats from Orthodox Muscovy (Russia), the Muslim Ottoman Empire and Lutheran Sweden, Catholicism became an increasingly important aspect of Polish national consciousness.

Briefly in the 1620s, it seemed in Rome that the entirely of Protestant Europe was on the verge of being reclaimed for the Church of Rome as Habsburg armies marched to the Baltic and Charles I of England married a Catholic princess but Ferdinand II overreached himself and the English monarchy did not become a vehicle for re-Catholicisation. In 1635 the Peace of Prague re-stabilised the religious border in Germany and Catholic France went openly to war with the Habsburgs.

What forces allowed for this remarkable recovery? It is important not to underplay the role of coercion. Catholic states, with some exceptions such as Poland and Royal Hungary, persecuted heretics (just as states such as England and Denmark proscribed Catholicism).

But repression was never the whole story. A huge educational and mission endeavour underpinned the Counter-Reformation much of which was consciously designed to inoculate the faithful against the seductions of Protestant belief. Clerical training and education improved dramatically and they in turn provided a high quality of consciously Catholic schooling for the European elite. Catholicism developed a highly varied panoply of devotional practices which reached out to the simple as much through the senses and the emotions as the mind while offering the educated a much richer theological and spiritual diet.

In effect, while maintaining much of its medieval inheritance, Catholicism responded to many of the criticisms of the reformers (and their Catholic predecessors) and like the Protestant confessions became focused on the project of how to create a new and, from their perspective, better type of Christian.

Remodelled confraternities, a wide literature ranging from simple catechisms to such texts as Francois de Sales’s enormously popular Introduction to the Devout Life, religious theatre and songs, concentrated missions by regular clergy which supplemented much more bureaucratic oversight by the parish clergy of morals and religious practice, pilgrimages and processions, devotions such as Loreto, the 40 Hours and the Child of Prague, all became instruments in the transformation of spiritual life of the general population.

So successful were some of the devotional texts such as de Sales’s Introduction or Robert Persons’s Christian Directorie that they ended up being translated (with some cosmetic alterations to disguise their Catholic origin) for a wide readership in Protestant Europe.

The consolidation of Catholicism was also helped by the contemporary splintering of Protestantism into various different doctrinal positions which enormously bolstered confidence that the Church of Rome was the only credible candidate with the history and the range to be the institution against which the gates of hell could not prevail.

After the Council of Trent, there was no room for the peaceful negotiation of the reunion of Latin Christianity: the era of the Counter-Reformation instead was one of fierce competition between different brands of Christian belief. And within that context, on a whole variety of levels, Catholicism competed very fiercely indeed.

The Council of Trent by Pasquale Cati, Santa Maria in Trastevere, Rome, 1588.

The Council of Trent by Pasquale Cati, Santa Maria in Trastevere, Rome, 1588.