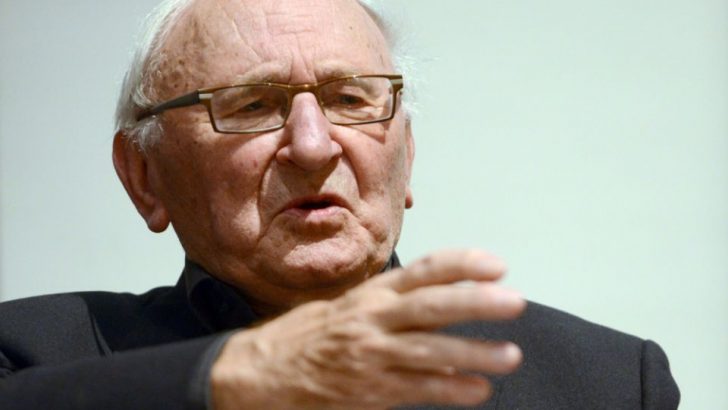

Catholic theology lost a giant last Monday with the death of German Fr Johann Baptist Metz, a disciple of famed Jesuit theologian Karl Rahner and the father of what was known as “new political theology”, at the age of 91.

I first encountered Metz more years ago than I care to remember, when I was a cub reporter for the National Catholic Reporter sitting in a newsroom in Kansas City, Missouri. There was a lot of Catholic news out of the German-speaking realm at the time (as there is today, of course), and because I’d picked up a smattering of German in grad school, by default I ended up keeping an eye on things.

In 1998, I covered a story centring on Metz, who was celebrating his 70th birthday. A number of friends in the theological guild had organised a symposium in Ahaus in Metz’s honour, and to the surprise of many, a star guest had agreed to be the featured speaker: then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, at the time the Vatican’s doctrinal czar and a sort of love-to-hate figure for many in Metz’s circles.

Ratzinger’s appearance raised eyebrows, and not only because he and Metz frequently had crossed theological swords over the years. (Among other things, Ratzinger saw the roots of Latin American liberation theology, and the distortions of it he faced during the 1980s, in Metz’s work. As a point of fact, the Brazilian Franciscan Leonardo Boff, perhaps the most pugnacious of the liberation theologians, studied under Metz.)

Permission

The animus between Ratzinger and Metz was also personal. In 1979, when Ratzinger was the Archbishop of Munich, he denied Metz permission to accept a teaching appointment at the local university.

Later, Metz was among the signatories to a statement criticising Vatican attempts under Ratzinger to erode academic freedom, and Metz also signed the famed “Cologne statement” in 1989 Complaining that the collegiality called for by Vatican II was “being smothered by a new Roman centralism”, and predicting: “If the Pope undertakes things that are not part of his role, then he cannot demand obedience in the name of Catholicism. He must expect dissent.”

Thus when news broke that Ratzinger would go home to honour his longtime antagonist, it was generally applauded as a moving gesture of letting bygones be bygones. That sentiment, however, wasn’t universal, including Swiss Fr Hans Küng, the enfant terrible of liberal German-speaking theology, who blasted Metz for agreeing to appear with Ratzinger without demanding reforms, including the nature and function of the Vatican’s doctrinal office.

Küng’s volubility on the subject had the effect of politicising what was supposed to be a happy birthday celebration – which some saw as distasteful, but others as ironically fitting for the father of political theology.

As all this was unfolding, I reached Metz by phone at his home in Münster, where he had recently retired from the theology faculty after a 30-year career. I explained I was a reporter from the US, and, after modestly expressing surprise I was even interested in him, Metz agreed to discuss the situation.

Maybe it was just my good luck to catch him at a stage in life when he was beyond caring about the diplomatic implications of whatever he said, but Metz was remarkably candid. He confirmed in no uncertain terms, for example, that he believed the way the Vatican’s doctrinal office was functioning under Ratzinger was out of keeping with the vision of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), and said he planned to bring that up with his longtime colleague when they were together.

Anyone who ever spoke with Metz understood that for him, Faith came first and politics second, however indispensable he may have regarded politics to be”

Yet when I asked if he therefore agreed with Küng that he shouldn’t have agreed to share a stage with Ratzinger, Metz was equally firm that he didn’t.

Here was the money quote: “You know, sometimes Hans behaves like another magisterium,” Metz sighed. “To be honest, one is more than enough for me!”

In all my subsequent experiences with the man, there was always at least one fall-down-laughing quip like that, indicative of Metz’s devastating sense of humour. He had a little bit of the typical arrogance of the German Doktorvater, but it was always leavened by a capacity to laugh at himself, his colleagues, and the general situation in which he and the Church found themselves.

Born in Auerbach in 1928, Metz studied in Bamberg, Innsbruck (where he met Rahner) and Munich, and was ordained in 1954. He taught at Münster from 1963 to 1993, and after Vatican II he also acted as an adviser to what was then the Vatican’s “Secretariat for Non-Believers”, which later evolved into the Pontifical Council for Culture.

Metz was also among the co-founders of the theological journal Concilium, which became the leading forum for the liberal wing of the reform camp at Vatican II in the years after the council. He was a key adviser to the West German bishops during their synod from 1971-75, which ended with a statement titled “To Our Hope” that carried Metz’s signature.

Like Rahner, Metz regarded Gaudium et Spes as the summit of Vatican II’s teaching: “The joys and the hopes, the griefs and the anxieties of the men of this age, especially those who are poor or in any way afflicted, these are the joys and hopes, the griefs and anxieties of the followers of Christ.” He applied that thrust in the realm of politics, insisting that a Christianity not politically engaged on the side of the poor was inauthentic.

Ideas

It perhaps wasn’t his fault that he was developing those ideas in the context of 1968, the Cold War, and the emergence of a modern politics of identity, in which it was far too easy for the “option for the poor” to be read in an ideological key. One could also argue that Metz, again like his mentor Rahner, was overly optimistic about what politics could achieve, insufficiently cognisant of sin – Hans Urs von Balthasar once actually accused Rahner of negating the necessity of the crucifixion.

Yet anyone who ever spoke with Metz understood that for him, Faith came first and politics second, however indispensable he may have regarded politics to be. He also never took himself or his work excessively seriously, trusting that over time things would sort themselves out as they should.

That’s probably about the best epitaph one can provide for a theologian’s life, so requiescat in pace, Johann Baptist Metz, and know that you will be missed.

John L Allen Jr is Editor of Cruxnow.com

John L. Allen Jr.

John L. Allen Jr. Fr Johann Baptist Metz

Photo: (CNS/KNA/Harald Oppitz)

Fr Johann Baptist Metz

Photo: (CNS/KNA/Harald Oppitz)