A new deal on the State files annual release

This year the reports on the State files’ annual release, which has become very much a fixture of the turnover between Christmas and the New Year, will take a different form as it appears in the pages of the papers and in other media.

Rather than as before a very large number of up to 25 or more journalists, competing for stories against each other, a pool system has been run to which the much smaller number of reporters shared between them what stories they found of interest.

This means a change in our approach as well. This year rather than a series, I am filing a report on a single set of documents, the release of files from the Office of the Film Censor covering 1924-1965.

They are revealing of social and political changes over those years in relation to public entertainment, public morality and a perceived threat to Ireland’s own culture. This approach is how, in fact, the masses of documents preserved over the centuries in the National Archives are meant to be used.

***

Some four decades of files from the Office of the Film Censor cast new light on the changing nature of Ireland from the first days of the Irish Free State in 1923 to the arrival of television in the early 60s.

Though films had been shown in Dublin since the 1890s it was the arrival of the comedies of Chaplin and others that turned “the pictures” it into a mass international entertainment from 1910 onwards.

However, the nitrate stock on which the images were recorded was highly flammable and there were many accidents due to fire. In Ireland local authorities attempted to control the cinemas and films to some extent. In Britain the industry itself established the independent British Board of Film Censors in 1912 in order to pre-empt local censorship by issuing a national certificate.

Ireland took another path: the appointment of the world’s first state appointed film censor. With the coming of an independent State the new government repealed the old regulations and centralised the control of films in the Department of Justice and their censorship with the Censorship of Films Act 1923, which led to the appointment of a film censor with an office of his own, initially in a former cinema in O’Connell Street, near the main trade outlets, later in Molesworth Street near the Government, and finally in a small purpose built bungalow on OPW land on quietly respectable Harcourt Terrace, an elite location.

The first censor

The first censor was James Montgomery, appointed by Kevin O’Higgins, the Minister of Justice, on November 1, 1923. Though the scheme was widely supported, there was trouble with the cinema proprietors resulting in a temporary ‘boycott’, as the censor called it, which was soon smoothed out.

Mr Montgomery seems to have had no real qualifications for the position. He owed his appointment to his social and political connections with people like Senator Oliver Gogarty and other wits of the Dolphin Hotel coterie.

In his first reports, however, the films were not distinguished by title, but the total film length of imported stock was the recorded (an imposition perhaps by Customs and Excises). This makes it hard to judge the work of the censor.

It is significant that the government began with censorship of films, the great form of mass entertainment for the working and lower middle classes, rather than books which were bought mostly by the educated upper classes. When officials spoke about public morality they were expressing fears about the ‘corruption of the lower orders’ (as the phrase then was).

But there seems to have been general agreement between censor and the social publicists and ‘influential laypersons’ about what was wanted. There was no need to consult the general public.

Catholic opinion here was greatly influenced by controversy on the matter of film controls in the US, and much of what was said in Ireland in 1923-24 had been said there in 1921.

The censoring of silent films was simple enough; the objectionable matter could simply be edited out. But arrival of “talking pictures” over the course of 1929 presented technical difficulties for Montgomery, for while the images would be harmless, for the sound (which was on a magnetic strip on the film was not beside the image but in advance of it) a jump cut would not work. The censor found it easier simply to reject films, rather than cut them.

The introduction of the Hays Code in the United States in 1930 (sternly enforced from 1934 on into the 1950s, initially by an Irish Catholic) was also a creation of the industry itself to protect its theatre chains from local censors in places like Boston. This ‘clean screen’ movement certainly improved American films in the eyes of James Montgomery.

(The sort of thing objected to is well illustrated by new Irish star Maureen O’Sullivan’s 1932 pre-Hays Code film Tarzan the Ape Man, which has a nude swimming scene and one of her undressing behind a white screen. It opened in Dublin, trimmed of the more revealing moments, for Christmas 1932 – “the most sensational film of the year”, according to the posters outside the Savoy.)

Having established the strict procedures of Irish film censorship, in 1940 Montgomery having reached the age of 70, retired in September. The press on this occasion spoke well of his time as censor, saying that there had been few criticisms from either the public or trade.

The government, with all the new concerns of the ongoing war, appointed Richard Hayes, the Director of the National Library, to the post. Born in 1902, he was an old Clongowes boy and a graduate of Trinity College Dublin, as well a director of the Abbey, which was held against him in some quarters. Others wondered why the post (at £900 a year) was not advertised. But the public were not privy to what was going on behind the scenes.

Hayes was perhaps an inevitable choice in the day, given the existence of the wartime Emergency Powers Order, under which the country was being run. This was because Hayes was central to the government’s counter-intelligence work as chief code breaker of suspect cable and radio traffic from the German Embassy and other legations.

An essential part of his role as film censor at this date was to view and edit the cinema newsreels, such as Time Magazine’s popular newsreel, ‘The March of Time’ from the then neutral US.

Issues of this series were indeed rejected, but afterwards they were allowed in after they had been re-edited to meet the demands of Irish neutrality. The concern to preserve Ireland’s neutrality went on down to the end of the war and was very strictly applied to British film, especially those dramas dealing with the war.

In general the war meant a reduction in the numbers and suitability of films from both the US and Britain. But with the end of the war there was a return to the former large importations.

Strange decisions

Dr Hayes was perhaps stricter that Montgomery had been, preserving the same social norms that affected Irish society. James Montgomery served for some 16 years, Hayes would last 14. In that time he made some strange decisions.

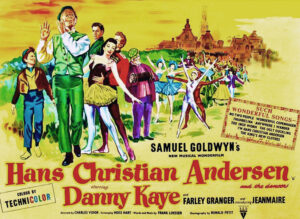

This is illustrated by the matter of the Danny Kaye vehicle Hans Christian Andersen (1952). When it was originally offered for censorship late in the year the censor demanded cuts which the producers refused to make, at which he simply rejected the whole film.

The film, however, was released in Dublin in the autumn 1953, a year late, after undisclosed cuts. The screen play was drawn from a story by Myles Connolly, the noted Catholic novelist, author of Mr Blue (1928). The Catholic Standard was distinctly cool in its review, though the film was warmly praised elsewhere.

The trouble was Hans’ infatuation with a beautiful ballerina at the Royal Danish Ballet, who was married to a husband she loves with whom she bickers. Hans writes The Little Mermaid, which is made into a successful ballet. Only then does the deluded Hans realise the folly of his love for the ballerina and he returns home.

The theme suggestive of adultery in what was seen as family Christmas entertainment led to the rejection. All of this suggests that Dr Hayes lacked the sensitivity and understanding of films in a cross-cultural context.

But he and James Montgomery had established the pattern by which the films were edited to make them suitable for, say, 12-year-olds on Saturday afternoon’s shows. Most provincial towns now had a cinema, and in greater Dublin alone 32 cinemas could hold 40,000 people a night.

Dr Hayes was followed by Martin Brennan, a Sligo doctor with a national record as a commander in the South Sligo brigade of the IRA, who had an interest in drama and the language movement.

He died in 1956, to be succeeded by Liam O’Hora, a Dublin barrister, with a mixed career who had previously been the manager of the Gaiety Theatre in Dublin for seven years – earlier he had been in the Irish Army and then in the notorious Palestine Police under the British Mandate.

O’Hora found the atmosphere very difficult with the censor now open to a great deal of public criticism, which he did not care for. In his report for 1963, he remarked plaintively, about the emerging culture of modern Ireland, that: “The overnight transition from standards of Our Boys to those of Greenwich Village deserved an explanation.”

After him came Dr Christopher Macken, appointed by Mr Haughey on April 13, 1964. He lasted to 1972. However, the files just released pause with 1965 – the year Dr Macken banned the German expressionist film The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, a German silent classic made in 1920. Horror films of all kinds had long been, perhaps rightly, a concern of all the censors, worried about their effect on a younger audience.

That year in fact Dr Macken banned twice as many films as the year before. His heavy hand soon drew the criticism of the newspaper film critics, who were now increasingly professional in outlook and well informed about international cinema, especially Italy and France. Continental films were more common now, with two cinemas devoted just to them alone in Dublin.

Irish television

Then there were Dr Macken’s fears for the arrival of television in Ireland.

Those living along the Leinster coast had been able to receive British television transmissions from Ulster and Wales since the early 1950 – it was said that some 700 television sets were sold before the Coronation in 1953.

Families without one would finish their Sunday family drive with tea in a hotel to watch the Sunday serial, then of a religions kind, from the BBC such as Paul of Tarsus in 1960. The Maigret series also in 1960 was also a great hit in Ireland. RTÉ met these with popular comedies from the US to counter the appeal of Coronation Street on ITV.

But the introduction of an Irish television service, which began broadcasting on December 31, 1961, was also altering the setting for the film censorship debate which was growing in volume.

There were calls of the introduction of a properly graded age-related certificate for film censorship to overcome the anomalies that were all so obvious. Also the appointment to the post of party stalwarts by both main parties seemed to need to become more open to many.

The film censors all claimed to have in mind when going about their work the ‘average Irish family’. But new academic studies showed that the average Irish family and what they thought and believed, was not as the censors and many public figures imagined them to be.

It could be said that the main audience of film in Ireland lived in the world described by Jesuit sociologist AJ Humphries in The New Dubliners (1966) which specifically dealt with the consumption of the media, while the censors and many politicians lived in the fast fading realm described by anthropologist Conrad Arnsberg’s The Irish Countryman in 1936.

A new kind of clerical expert on culture emerged too, notably Fr Donald O’Sullivan of the Arts Council, Prof. Fr Peter Connolly of Maynooth, Fr John Kelly, Fr Micheál MacGréil SJ, and others. Then there was in Dublin the creation of the Irish Film Society which could show uncertified films often from the Continent to private middle-class audiences in a club. The huge increase in university graduates since the 1950s meant there was a very different and enlarged audience generally for all the arts.

In the schools the watch word of the day was ‘the mature Christian’, the informed and educated Catholic needed for a modern society which was no longer the ‘Catholic state’ so many nationalists had once spoken about. This mature Christian was inevitably seen as the mature citizen of the future too.

Then there was the television lecture series The Course of Irish History, a resumé of what modern academic historians believes to be the case about the past and present. This altered many old uncomplicated views, and remains a standard work which all can be considered to have read or at least been influenced by.

Nor indeed in the early 60s could Liam O’Hora and Dr Christopher Macken readily fall back on the Department of Justice for support where the permanent secretary of the day whose advice they had been advised to take was an admitted atheist.

So the years from 1969 to 1972 would be very difficult for the then Film Censor Dr Macken. He found the new Ireland an uncomfortable place. But we will have to wait another year before I learn more about the crisis years that followed down to 1972 and after.

[This appraisal is based on a release from the Office of the Film Censor Annual of reports covering 1924-1965, FOC 2023/133/1-32, now currently available to the public in the National Archives in Bishop Street, Dublin…

There are other documents relating to the Film Censors Office in earlier transfers which we have not had a chance to examine, but those interested can inspect them.]

Peter Costello

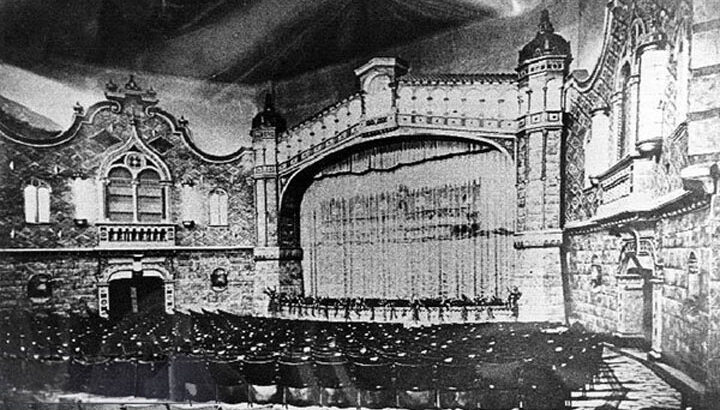

Peter Costello The Savoy cinema, Dublin, in 1929, typical of the movie dream palaces of the great era of film going. Photo: Archiseek.

The Savoy cinema, Dublin, in 1929, typical of the movie dream palaces of the great era of film going. Photo: Archiseek.