Safeguarding Sunday has become a regular feature on the calendar of the Archdiocese of Dublin.

The idea is to ensure that parishes and communities are acutely aware that the safeguarding of children and vulnerable adults was not a single moment or piece of work that was undertaken in reaction to sickening abuse reports, but the permanent work of the Church.

The aim is to promote the highest standards, and to remind everyone involved in the Church that safeguarding is a standard practice for us all, that it is part of the culture of our Church here in Ireland.

In recent decades, thousands and thousands of parishioners have volunteered to undertake stringent safeguarding training and are now part of a wide network of volunteers ensuring that parishes and Church activities are safe. In every Church setting in Ireland, almost the first thing that one sees on entering is the safeguarding policy with contact details for those who should be notified if there is a concern. Almost every parish bulletin and website in the country has similar details.

To say that the old culture has changed in the Catholic Church in Ireland would be an understatement. Supervised by the independent National Board for Safeguarding Children in the Catholic Church in Ireland (NBSCCCI), the handling of allegations or concerns of abuse today would be unrecognisable even 20 years ago.

Above all, the victims and survivors who came forward to speak of their experiences deserve immense credit for this. If they had not held the Church’s feet to the fire, the culture may not have changed. Those parishioners and priests and religious who stepped forward to take on this mammoth task also deserve great credit.

They have truly been part of a cultural revolution in Irish Catholicism away from denial and cover-up to acceptance and accountability. It truly was an exercise in synodality and co-responsibility before these were everyday concepts in the universal Church.

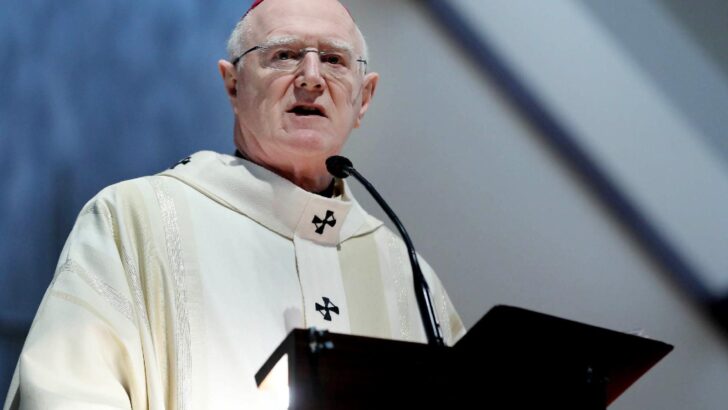

It is disappointing therefore, for these people, that in his homily for Safeguarding Sunday Archbishop Dermot Farrell chose not to mention the huge cultural shift, or to pay tribute to the sterling work that has been, and is being, done.

It is understandable, perhaps, that in the light of the recent Scoping Inquiry he may feel that the time is not right. Yet, any fair assessment of where the Church is at now will acknowledge that the culture revealed in that inquiry is a different one from today, thanks to herculean efforts by laity and priests.

While Archbishop Farrell clearly wants to demonstrate that he ‘gets’ the abuse crisis, the headlines generated by his homily such as ‘No Church reform until abuse crisis addressed’ gives the wrong impression that nothing has been done to address the crisis.

At one stage, the archbishop describes reactions to the inquiry: “while some are filled with anger, others close their ears, or dismiss it, or explain it away, or blame the extensive coverage on hostility towards the Church, there is a thread of denial and disengagement in many of these responses”.

This was certainly the case for a very long time, but, in the experience of this newspaper, that has not been the case for a very long time. Who is he referring to?

The archbishop’s contention that there can be no reform in the Church until abuse is “fully addressed” is almost exactly what the Irish Synodal Delegation told the Continental Assembly in Prague in February 2023.

Where does that leave the Archdiocese’s own ambitious ‘Building Hope’ reform programme?

The truth is, the work of addressing the abuse crisis goes hand-in-hand with reform. The Gospel cannot be held in stasis while the episcopal and religious leaderships try and extricate their institutions from a moral, legal and financial quagmire. Outreach to victims and survivors goes on, and yes the quiet work of building faith, hope and love goes on, ‘for those who look only to the past or the present are certain to miss the future.’

It would be a pity if Catholics got the wrong impression from the archbishop’s unrounded remarks, as it is disheartening indeed to the thousands of ordinary Catholics who have worked for the very culture change that is before our eyes. Instead of just a homily from the Pro-Cathedral, where there is no dialogue, maybe the Archbishop would host listening sessions in parishes, openly engaging with the church and all its people. Maybe a Diocesan Pastoral Council will open up that discussion.

Archbishop Dermot Farrell. Photo: OSV News/courtesy John McElroy

Archbishop Dermot Farrell. Photo: OSV News/courtesy John McElroy