Greg Daly explores the historical roots of the mentality that created Tuam’s Mother and Baby Home

History and commemoration are, as President Higgins observed in a speech in Dublin’s Mansion House almost exactly a year ago, different things.

Commemoration, he noted, is typically mediated through present-day concerns, and stands always in danger of being exploited for partisan purposes, at risk of the backward imputation of motives, the uncritical transfer of contemporary emotions onto the past, and forms of public history intended to secure the present “by invoking an ‘appropriate’ past, or, in desperation, by calling for such an amnesia as might allow a bland transition to the future”.

The President’s speech at the ‘Remembering 1916’ symposium was remarkable both for the wisdom of such observations and for its failure to abide by the warnings it sounded. Deafening by its silence in the speech was an acknowledgement of the extent to which the Easter Rising had been, in many ways, a religious rebellion by a religious people.

Religion is alluded to in the speech only in the context of the recruitment campaigns of what President Higgins called “a supremacist and militarist imperialism”, an unexplored reference to the Easter Proclamation’s guarantee of religious liberty, and a lengthy criticism of what the President described as a “conservative reaction” to the ideals of 1916. Independent Ireland was in its early decades increasingly subjected to hierarchical and patriarchal values, he said, observing that a property-driven conservatism became Ireland’s dominant ideology.

Private property

“The fetishing of land and private property, a restrictive religiosity, and a repressive pursuit of respectability, affecting in particular women, became the defining social and cultural ideals of the newly independent Ireland,” he said.

In fairness to the President, his analysis of how Ireland’s economy and society had been transformed in the decades ahead of the Rising, though simplistic, had merit: the Famine and subsequent emigration had annihilated Ireland’s landless labourers, while the Land Acts had turned tens of thousands of rural tenants into peasant proprietors.

“Beyond any notion of sufficiency or security of tenure, a new grazier class emerged, often in alliance with professionals and with those who controlled rural commerce and credit,” he said, continuing, “These were the classes who would be set to rise in the new State.”

For the President, this native class of conservative landowners, whose ideology merged notions of class, property, and respectability, would smother the radicalism of the Easter Proclamation and the Democratic Programme of the First Dáil.

There’s something to this thesis, of course, and any number of anecdotes can be drawn on to support it but numbers alone should make us reject that what happened after independence was in any sense a betrayal of or reaction to the cause of independence.

The very first meeting of the First Dáil was attended by just 27 of the 105 MPs elected in the 1918 general election, with 42 of Sinn Féin’s 69 MPs being absent, the bulk of the absentees being detained at the pleasure of His Majesty. Subject only to the briefest of the debates, the Democratic Programme had been in its first draft, according to historian Joe Lee, “an attempt to foist on the Dáil a programme that had never been presented to the electorate”.

Even its hastily redrafted final form, Brian Farrell wrote in The Creation of the Dáil, did not represent the social and economic ideas of the First Dáil, and, Lee notes, incorporated more of the social doctrine of the Easter Proclamation than the electorate could realistically be deemed to have sanctioned.

If it is difficult to make a case that the social intentions of the Democratic Programme of the First Dáil had popular legitimacy, being suppressed only by an elitist conservative counter-revolution, an investigation of subsequent elections should quash such claims.

With men and women having equal voting rights from 1922 on, elections through the 1920s and 1930s saw parties that most would deem socially conservative – leaving aside how for much of that period the Labour Party was hardly a radical group – getting 68%, 77%, 72%, 80%, 82%, 89%, 80%, and 85% of the vote.

Inconvenient truth

If Ireland was a socially conservative country, it was because Ireland’s voters – women as much as men – voted for it to be so.

That the vast majority of these voters were Catholic is a truism; although the Catholicity of the bulk of the rebels of 1916 and the War of Independence is at best an inconvenient truth for many nowadays who would laud those who took part in our independence struggle, so the “restrictive religiosity” of the new State is a convenient stick with which to beat the Catholic dog.

For too many, the story of the first decades of Irish independence can easily be told: the Church dominated the State, Irish politicians fawned before the Church, and if Catholic ideology dominated in Irish society, well, this was only because long years of clerical control had conditioned Irish people to toe a Catholic line.

It would, of course, be nonsense to claim that the Church was not a key influence on the mind of Irish society during the decades on either side of our independence struggle, but it would just as nonsensical, however, to claim that it was the only such influence or to deny that Irish society was a key influence on the mind of the Church.

Indeed, there’s a strong case for asking, as Fr Vincent Twomey did in his 2003 book The End of Irish Catholicism?, just how Catholic ‘Catholic Ireland’ was through the 19th and 20th Centuries.

A clue that something was amiss can be seen most obviously in the attitudes of newly independent Ireland to poverty and destitution. “In truth there was often a tendency to see poverty as representing a flaw in the national character: a lack of thrift, independence, or of ‘manly desire’ to want to earn a living,” observes Diarmaid Ferriter in The Transformation of Ireland 1900-2000, in an analysis of the ‘moral panic’ that was rife in 1920s Ireland and that the Church had played no small part in stirring up.

Treasury in Heaven

That such an interpretation of poverty was alien to Catholicism and traditional Christianity should not need saying. The Book of Daniel, after all, had assumed that money given to the poor could pay down a debt built up in Heaven, with Tobit deploying the image of a treasury in Heaven funded directly by almsgiving and Sirach identifying the poor as a class of people through whom one could demonstrate reverence for God.

Almsgiving for the purposes of reconciliation was central to the thinking of the early and medieval Church, aware as it was of these Old Testament teachings and Our Lord’s words in Matthew 25 about how love shown to the poor was, in practice, love shown to God himself.

This understanding unravelled during the 16th-Century Reformation, when Protestants banished Tobit from the Bible and rejected the notion that good works were necessary for salvation, casting them instead as important signs of salvation, for which all that was needed was faith in Christ alone.

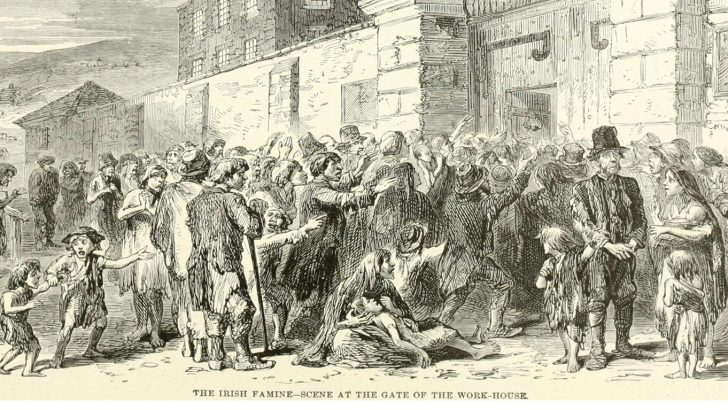

The workhouse system in England arose as a solution to the growth in visible poverty following the dissolution of the monasteries that had cared for the poor, regardless of whether poor people were deemed to deserve help or not. In time distinctions were drawn between those poor who were ‘deserving’ and those who were not.

By the time of the Acts of Union in 1800, over two million people in Ireland lived in destitution, and the first decades of Catholic ‘respectability’ since the Reformation and Penal Laws saw the introduction of British institutions – notably workhouses during the period of the Famine.

It also gave birth to a provincial mentality, with Ireland now simply a part of the UK. This led over time to Irish Catholicism taking on a new character, one marked by whatever devotional reading was available in English and where the same social pressures that drove the abandonment of the Irish language also promoted and inculcated a tendency to conform to the norms of respectable Victorian society.

The result, Fr Twomey observes, was in some ways “a Protestant culture decked out in some second-hand Catholic garments”.

The first decade of independence would be the decade that saw the genesis of the Mother and Baby Homes, an offshoot of the workhouses or ‘county homes’ that were, with the industrial and reformatory schools, Magdalene laundries and psychiatric hospitals, part of the what the 2013 McAleese Report identified as the new State’s “inherited networks of social control”.

The same decade saw a decision to ramp up reliance on the industrial school system such that even as early as 1924, independent Ireland had more children in industrial schools than did the entirety of the UK.

Throughout the 1920s it was a commonplace that Irish morality was in decline, and it is no coincidence that this was a concern beyond Catholic conversations.

High reputation

As Ferriter notes in Occasions of Sin: Sex and Society in Modern Ireland, even the Protestant-oriented The Irish Times decreed in a 1927 editorial that: “Throughout the centuries, Ireland has enjoyed a high reputation for the cardinal virtues of social life. She was famous for her men’s chivalry and for her women’s modesty. Today, every honest Irishman must admit that this reputation is in danger … our first need is full recognition of the fact that today the nation’s proudest and most precious heritage is slipping from its grasp.”

This sort of language was hardly unusual in the Europe of the day, still traumatised as it was by the devastation of the Great War and the social turmoil that had unleashed, but it had extra frisson in newly independent Ireland, determined to justify its independence after centuries of foreign occupation. The Easter Proclamation had pledged the lives of Irish people to their country’s “exaltation among the nations”, with Ireland being called to an “august destiny”, this being, it was clear, to be the teacher of the nations, once more the bearer of Christian truth and wisdom.

There would be little point in talking such a talk without walking the walk too, of course, so the prospect of Ireland’s moral decline – testified to by, among other things, rising numbers of extramarital births – was terrifying. Sex was a threat as potent as poverty to Ireland’s desired image, and had been so since the Famine.

“The technique of birth control devised by post-famine Ireland, late and few marriages, required vigorous self-control from the disinherited, and indeed from the inheritors until they belatedly came into their legacy,” observes Lee.

Noting that the only way to protect the property interests and social structures of Ireland following the Famine was to lay an “exceptional emphasis” on the perils of sex, he observes that Ireland’s clergy, Catholic and Protestant, were children of a society that believed it needed this emphasis.

Early attempts to dismiss Catherine Corless’s research claimed any bones found there were simply ‘Famine graves’. In a strange and profound way, it appears that they were just that.

Greg Daly

Greg Daly Peasants at a workhouse gate during the Famine

Peasants at a workhouse gate during the Famine