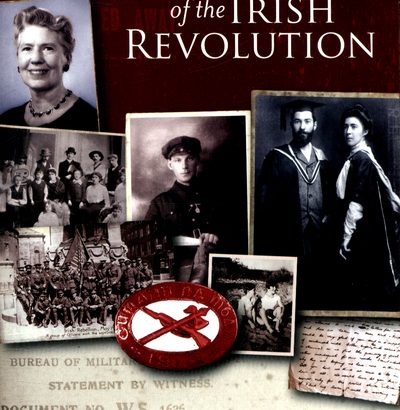

Family Histories of the Irish Revolution

edited by Ciara Boylan, Sarah-Anne Buckley and Pat Dolan

(Open Air, €24.95)

J. Anthony Gaughan

This collection of interesting essays concern persons who in one way or another were involved in the revolutionary years from 1913 to 1923. The essays are by relatives of these activists, some of whom were well-known, others less so.

Francis Sheehy Skeffington was a journalist who championed progressive causes, not least feminism. Ironically he was murdered during Easter Week 1916, when attempting as a pacifist to restore order. Micheline Sheehy Skeffington records how his son, Owen, continued his crusade for equality and justice in society.

Peadar O’Donnell was one of the most controversial and well-known figures in the revolutionary period. A radical socialist, he berated the leaders of the independence movement for their lack of commitment to radical reform.

Tom Boylan describes O’Donnell’s life as teacher, trade-union organiser, IRA activist and writer. He also records O’Donnell’s curious and ambivalent relationship with the Catholic clergy. While in his public persona at war with them, at the same time he counted some of them as cherished friends.

Niamh Reilly describes “the many sides” of Tom Kettle: the writer, speaker, politician, academic and soldier. He was in Belgium at the request of the Irish Party buying arms for the Irish Volunteers when Germans invaded. He witnessed their systematic aggression against civilians and how they destroyed everything in their path, including churches.

Conviction

This and his conviction that nationalists and unionists fighting together would advance the cause of independence caused him to join the British army and die for Ireland at the Somme. Reilly acknowledges the validity of the narrative of Tom Kettle as the fallen World War I soldier, constitutional nationalist, and good European who fell on the wrong side of post-1916 Irish history.

However, she claims much more should be included in a discussion on his legacy, not least his work in relation to labour and women’s rights.

Michael Lang writes about the varying fortunes of John Dillon, his grandfather, and Michael Lang, his grand-uncle. Both joined the RIC in peaceful times; both were promoted to the rank of sergeant in 1910. As the tempo of the war of independence ratcheted up in 1920 members of the RIC from a nationalist background were faced with challenging dilemmas.

In that year Michael was serving in the Phoenix Park Depot in the RIC reserve and he was single. John was attached to the barracks in Killeshandra and he was married with a family. At the behest of the independence movement Michael resigned in October 1920, John continued to serve in the force until it was wound-up. Michael and others who resigned were awarded lesser pensions than those who stayed until disbandment and several successive governments failed to rectify that injustice.

Anthony Wheatley contributes a valuable account of Jack Morrogh’s involvement in the 1916 Rising. A Corkman, Morrogh fought and was wounded in World War I. Stationed in Dublin at the time of the Rising, he had a major role in suppressing it. Wheatley claims that it was he who called in the final devastating bombardment which forced the Irish Volunteers to surrender.

After the surrender Morrogh and other officers were photographed at the base of the Parnell monument with a captured Sinn Féin flag.

The picture appeared in the press. As a result Morrogh when living in Cork in 1920 was a ‘marked man’. He escaped death only because his wife and children were with him when his car was stopped by the Carrigaline unit of the IRA. Immediately after the incident he and his family emigrated to Argentina.

These essays by past and present members of the staff of National University of Ireland Galway are very worthwhile. They shed new light on aspects of the revolutionary period while casting a rightly critical eye on its legacy.