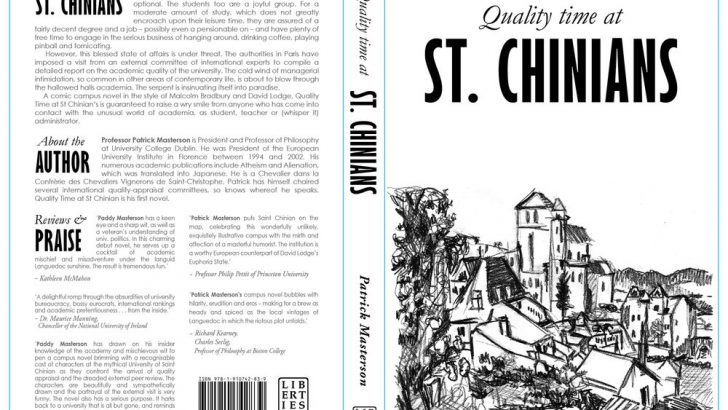

Quality Time at St Chinian

by Patrick Masterson (Liberties Press, €14.99)

Many people have enjoyed Ronald Searle’s The Terror of St Trinians and its sequel of comedy films. With an unmistakable reference to it in the title, Masterson provides a foretaste of this debut novel. Just as Searle described the eccentricities and idiocies of the staff and girls in St Trinian’s he highlights the cynicism and sense of self-importance of many senior academics.

He is well-qualified for this task. A former member of the philosophy department in University College Dublin, he served as president of the college from 1986 to 1993 and as principal of the European University Institute in Florence from 1994 to 2002.

Masterson creates his own university, names it St Chinian and locates it in the Languedoc in south-west France. It is a happy place, where some teaching is required but research is entirely optional. Even the students are happy.

For a moderate amount of study, which does not greatly encroach upon their leisure time, they are assured of a fairly decent degree.

There is, however, some consternation at the prospect of an up-coming external quality appraisal of St Chinian by a committee of international experts.

This was set in train by an ambitious secretary-general of the Ministry of Universities and Research in Paris. From the outset the aim of this initiative is clear. It is to steer the university away from its emphasis on liberal arts courses and programmes to pursuits which would be more useful to the business, industrial and tourist interests of the region.

Masterson’s record of the investigation conducted by the international committee sheds light on less-publicised aspects of university life.

There are the bitter disagreements between departments and sometimes a lack of civility between professors and other members of staff. The exceptional length of holidays enjoyed by academics is adverted to.

Then there are the over-generous perks, such as travel expenses for those engaged in research.

The author particularly enjoys poking fun at the patois in the schools of business studies and sociology. There is more than a glimpse at the rarefied world inhabited by senior academics and administrators where rich food and fine wines reign supreme. And during their week at St Chinian two members of the visiting inspection committee find time for romantic interludes!

In due course the report on St Chinian is presented and not surprisingly it is in line with the aims of the bureaucrats in Paris. However, it is dismissed by Guy Boulanger, president of St Chinian, in a rhetorical flourish and he is also able to ensure that once filed it would not see the light of day again.

Contempories of Patrick Masterson will have little difficulty in seeing him in the guise of Guy Boulanger. The former is well-known for his commitment to the concept of university education as outlined by John Henry Newman. Thus, in his rejection of the report of the international experts, Guy Boulanger, while acknowledging the role of the university in preparing students for the world of work, insists that a university’s priority is teaching students to think for themselves and to engage with concepts such as truth, goodness and beauty and the values they enshrine.

Throughout the author’s exhaustive knowledge of every aspect of life in to-day’s universities is clear.

His account of the foibles and pomposity of some senior academics and administrators takes the reader on a delightful romp.

The humour and irony is gentle without a hint of malice. And beneath all the fun there is a serious message.