We find ourselves entering the strangest Easter Triduum we have ever known. We will not gather for the Mass of the Lord’s Supper and the washing of feet. We will not kiss the cross. We will not light the night with paschal flames and banish the darkness as we proclaim the resurrection. There is no doubt that many of us will be present in spirit as we watch liturgies online, thanking God that technology makes it possible but still feeling the loneliness of being apart.

This year we are encountering the cross in a particularly painful way so it is worth thinking about that image, the cross and what our understanding of it is. It isn’t my intention to go into a heavily theological discussion but I do want to tease out some ideas to see where they lead us.

For a number of years I was a pastoral supervisor for seminarians on their pastoral year. I would visit them on placement and assess their pastoral skills in different situations, working with children and adults. Something which gave me cause for concern on a fairly regular basis was the tendency of lads to focus on the death of Jesus on the cross in isolation from either the life or the resurrection of Jesus. It often went along with a fondness for the story of Adam and Eve and the theme of original sin. The same themes emerged irrespective of the age of the group – children or adults – Jesus died for our sins. And my question is “Yes, but what do we mean by that?”

We need to explore where some of our ideas have come from. St Anselm lived in the eleventh century at a time when society was feudal – so the lord of the land was in charge and there was a very clear hierarchy which was seen as giving society strength and stability. If a peasant did something to offend his lord’s honour he would have to do something to make restitution. If he failed to do this or was let away with the offence by the lord then it would undermine the stability of the society and lead to social chaos. It was in the context of this understanding that Anselm developed his ideas about atonement and the cross of Christ.

Anselm saw humanity’s sin is an affront to God’s honour and nothing humanity could do would be enough to atone. Jesus is seen as satisfying the need to restore God the Father’s honour through his death on the cross. Only if God’s honour is restored can the relationship between God and humanity be healed. St Augustine spoke of Jesus as a substitute, taking our sins upon himself in order to repay the debt of justice owed to God. St Thomas Aquinas saw punishment as a morally good response to sin – so we should be punished if we have sinned. Christ takes on that punishment, not for his but for our sins. Baptism has made us one body with Christ so His atonement covers us too, for all the sins of the past as well as the present and the future.

If we stop and think about it we are all very familiar with this type of language, even to the point of being told that our sins have nailed Jesus to the cross but there are problems with this language. I want to unpack some of those.

When we focus almost exclusively on the cross and Jesus’ suffering there is a real danger that the only thing of consequence that Jesus did becomes his death on the cross. So his birth, the life he lived and his resurrection become little more than side shows. This does a disservice to the Gospel. It can also create a mentality where suffering becomes elevated and spiritualised. If we consider suffering to be divinely willed then we may be passive in the sight of others suffering, doing little to transform the circumstances and end the suffering. We are aware that suffering is a part of life but that does not necessitate adopting an attitude which implies “suffering is good for you” or that God is “testing your faith”.

The atonement theories of Anselm, Augustine and Aquinas among others also run a real risk of creating an appalling image of God. Do we really want to spread an image of God as the feudal lord who will not act to redeem his people until a debt has been repaid to restore his honour? An image of God the Father willing the death of Jesus in order to achieve a satisfactory atonement? An image of God who would inflict suffering as punishment?

Gerry W Hughes, the author of God of Surprises saw the danger in such language and how it could distort our image of God and infect our relationship with God. The language of Anselm, Augustine and Aquinas can seem more appropriate for the court room than for faith. Underpinning our relationship with God can be an image of one who records and counts every one of our sins, who weighs up our paltry efforts to make amends, who finds us wanting, who condemns us as inadequate. I remember some years ago an elderly uncle of mine was dying and was consumed with fear at the judgment he would face. My cousin, realising his father’s terror gently encouraged him to talk about his fear, urged him to let go of that terrifying image of God, to contemplate the God of love who shines out in the words and actions of Jesus. My uncle visibly relaxed and was able to put himself into the hands of God, trusting that he was loved and that whatever the mistakes and mis-steps of his life he would be forgiven. John stopped struggling and died peacefully but we were left with questions as to how as a Church we have allowed such terrifying imagery to paralyse the relationship of people with God.

We are saying then that the cross should not be taken in isolation. There is more to Jesus’ saving power than his physical suffering and death on the cross. His life, death and resurrection stand as one. Elizabeth A Johnson former Professor of Theology at Fordham University explores the theology of Anselm in her book Creation and the Cross. She understands what Anselm is trying to do but ultimately finds his theology inadequate, too narrow and legalistic. Drawing on both the Old and New Testaments Prof. Johnson offers an image of God who accompanies his people. As I have often written before, God’s desire is to be with us, God at the heart of our humanity and our humanity at the heart of God. Jesus is the divine expression of that desire. In Jesus’ life, death and resurrection Prof. Johnson sees a “double solidarity” – Jesus stands in solidarity with us even to the point of death and God stands in solidarity with Jesus. Yes, Jesus suffers on the cross, we must always be aware of the reality of that. The cross however is vital not because Jesus pays a debt with his blood but because it becomes a powerful image of how far God will go to be with us. Prof. Johnson speaks of the cross as “an historical sacrament of encounter with the mercy of God” and tells us that the cross makes “the compassionate love of God’s heart blazingly clear”.

The resurrection then sums up the life and death of Jesus. It confirms everything that Jesus has revealed to us – in word and action – about who God is. The resurrection makes clear beyond doubt that God remains with us even in the darkest depths and can draw new life out of each and every trial. God is experienced as liberating grace. The cross and resurrection of Jesus are one moment, a profound moment of incarnation, God with us.

St Anselm’s theology of the cross focuses on God-sin-humanity. Prof. Johnson pushes the boundaries out. In John’s Gospel we are told that when he is lifted up Jesus draws all things to himself. In Colossians 1:15 Jesus is referred to as “the firstborn of all creation”. The cross and resurrection of Christ are not just about personal redemption. The whole of creation is made new. This type of theology, the recognition that we are all connected, the peoples of the earth and the earth itself with the divine presence of God echoes through Pope Francis’ Laudato Si’. There he encourages us to accompany each other, to stand together in solidarity. The Irish proverb “Ar scath a chéile a mhaireann na daoine” – in the shade of each other the people thrive – stands true.

If the whole of creation is made new in Christ then he didn’t die just ‘for me and my sins’. There is a radical solidarity in the resurrection. We are living through a deeply painful paschal experience at the moment. The cross has the capacity to transform, to bring new life and meaning out of death and despair but it cannot be confined to personal transformation or individual benefit. It must be for the whole of creation. Many commentators have recognised that the Covid-19 pandemic reflects the vulnerability and ill health of the earth and that typically viruses such as this arise where people encroach on animal habitats and there is a loss of biodiversity. The nature of this pandemic has also brought home to us that we are one and we need to work as one in order to come through this. Pope Francis has spoken about how this Covid-19 crisis is not God’s judgement but it is a moment of judgement for us about how we will go forward. In the resurrection the fundamental interconnectedness of all creation is affirmed. We must now do the same.

So as we enter into the Triduum this year what may some of our thoughts be?

· That at the Last Supper Jesus places himself into our hands in the form of bread and wine – God’s free self-gift which invites us to be self-gift for others;

· That in the washing of feet we are reminded of our solidarity with each other and our call to serve;

· That in the cross we know that we are one, with a radical unity and a shared vulnerability;

· That God is with us even in the darkest of experiences;

· That in this time of suffering there is an awakening, a realisation of who we are called to be;

· That the fragility and vulnerability of creation is clear in the impact of Covid-19;

· That if we can listen to the cries of our world and our planet we can learn much about how we move forward in healing;

· That this situation is not ‘someone else’s cross’ but our cross;

· That in Jesus God has taken suffering into the very heart of the divine life and so we can come to God utterly as we are with all our fears, anxieties and questions;

· That Jesus suffers on the cross, not because suffering itself is a good thing but because he refuses to turn his back on us and on the message of God’s love which he brings. The political and religious powers create the situation in which Jesus is nailed to a cross. In solidarity with all the suffering of the world and her peoples Jesus on the cross is God with us. It is in this absolute self-gift that the resurrection is born;

· God’s liberating grace can bring light out of darkness, life out of death;

· Resurrection is not ours to horde but to share with all the earth;

· As Christians we are called upon to be people of the resurrection, to image forth God in our world. What image of God will we be?

As you move into Easter be alive to the glimpses of resurrection which surround you. Consider your five senses and reflect on your experience each day. Where have you encountered beauty, hope, love, joy?

· What have you seen?

· What have you felt?

· What have you heard?

· What have you tasted?

· What have you smelt?

We are talking glimpses, snippets of resurrection so pay attention to the small and ordinary things. Has a good cup of coffee raised your spirits? Laughter brought you joy? Heard the bird song outside your window? The smell of freshly cut grass to remind you that spring is here?

Give thanks for every glimpse of goodness which reassures us that we are emerging – slowly but surely – from the darkness and pain of these challenging weeks into the resurrection joy of Easter.

Bairbre Cahill

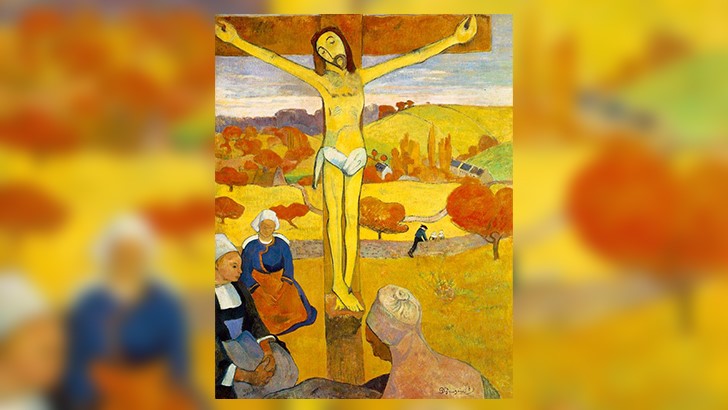

Bairbre Cahill The Yellow Christ (1889) by Paul Gauguin

The Yellow Christ (1889) by Paul Gauguin