The World of Books

Sarah Cecilia Harrison: Artist, Social Campaigner, and City Councillor edited by Margarita Cappock (Four Courts Press for Dublin City Council, €27.95/£25.00; paperback €22.95/£20.00)

Years ago when I was researching the interaction of the Irish cultural revival with other Irish national movements, the name of Miss S.C. Harrison was one I came across continually, but could not learn anything substantial about.

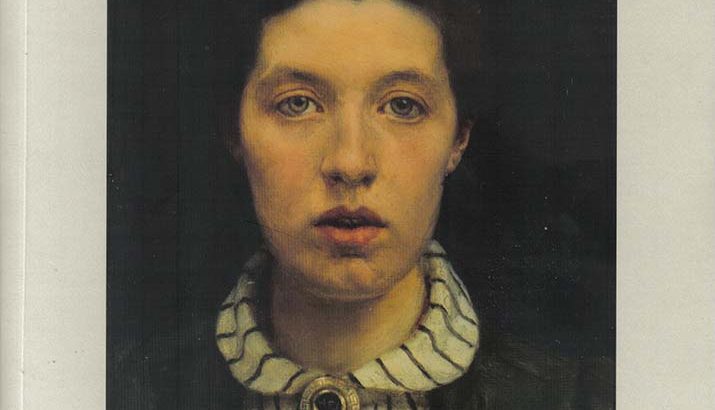

She was not only a political figure in Dublin city, she was a remarkable painter, who painted a portrait of George Moore, which proudly hung in his apartment in Ebury Street. It was Moore’s trilogy Hail and Farewell which gave imaginative shape to the literary revival in a way no other writer, not even Yeats and Joyce, did or could.

Disliked

Naturally he was disliked by many for making free with their private lives in what purported to be an historical record.

But of his portrayer in paint there was little to be learned of from others. Miss Harrison, perhaps because of the spread of her activities has been successfully ‘unpersoned’ as they used to say in Stalin’s Russia by others with far less talent or humanity.

Now at last there appears a book on her as an artist, activist and social reformer, Ulster-born, English-trained, Dublin-based, and it is most welcome.

Especially welcome is an attempt at a catalogue of her paintings, some 223 of them (and this is far from the full count). These images reveal the scope of her achievement, not so much its range, but the nature of her settled, absorbed style which they all have. In achieving this record Jim Gorry of the Gorry Gallery played a significant part.

The book contains four long essays, beginning with an overview of her life by the editor, followed by an account of her time at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, where she trained, by Hannah Baker; an exploration of her activities as suffragist and other political involvements, by Senia Paseta. These are closed off with an account of her time as a Dublin city councillor by Ciarán Wallace, where one aspect of her political work was revealed.

All of these are crammed with information, but they are really only preliminary studies to a full length biography. However it is to be hoped that this will be written by someone with the widest of interests, and that it is not too narrowly focused only one aspect of her many faceted life. There will be many people who will look forward this.

The focus of our interest in this decade of remembrance has been too much on the merely political and military, to the neglect of the general cultural revival, which is perhaps of much more lasting influence. We really need to get a wide view of what the cultural revival was: how it involved so many aspects of Irish life and society, which seem to have narrowed down to nationalist versus Unionist.

As a result we are tending to know more and more about less and less. When will someone write a book about a sense of humour as an Irish characteristic, or on the Irish perspective on the salvation of souls, from the point of view of all our creeds and cults. Perhaps someday.

Detail

These pages do not have room for fine detail in places. For instance, as it affects a matter in which I am greatly interested, I was disappointed that Ciarán Wallace makes no mention of her forthright opposition to the scheme to allow the artist James Ward, the headmaster of the Municipal College of Art, to decorate the inside of the dome of the Dublin City Hall rotunda.

These, I have always thought, were intended as a sort of counterbalance to the frescoes inside the Four Courts which showed scenes in the development of law. Law in Ireland often had a sternness unknown in England. So the City Hall, which belonged to the citizens in a more direct way, were to show 12 scenes from the mythical and legendary past of the city. They have in them a hidden nationalist agenda that is not immediately apparent; the ‘crowing’ of Perkin Warbeck in Dublin cannot be anything but a satirical comment on loyalism in Ireland!

Harrison was quite opposed to this scheme which had the support of the influential Alderman Tom Kelly: she wanted to retain the original state of the building as conceived by Thomas Cooley. Historic buildings were to be preserved, she thought, not ‘re-imagined’ as we say now.

It was only a small point. But her point of view was a sound one, which many would now agree with. But it revealed the determination with which she held her views, which applied across the board. She insisted the right thing should be done in all matters.

When she died in 1941 the stone erected over her grave in Mount Jerome was engraved ‘artist and friend of the poor’. An apt epitome of her life; but there was so much more. While we wait for the full length biography, the present book is a revelation which ought to be widely appreciated by anyone at all interested in the Irish cultural revival.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello