Frank Litton

The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism, by Martin Wolf (Allen Lane, £30.00/€34.50)

For all its faults, democratic capitalism is worth defending. But it is in grave peril” and “Democracy [in the United States] is not yet a lost cause. But it is highly endangered”.

These are not the words of a maverick seeking attention by crying wolf. We find them in the conclusion of Martin Wolf’s The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism.

Wolf is chief economic commentator with the Financial Times and a well-respected member of the establishment’s commentariat. He surveys the economic and political trends in western liberal democracies, with particular focus on the UK and the USA. They are, he reports, all heading in wrong direction.

Reason

We have good reason to welcome democracy. It allows us, at the very least, to mitigate, or undo, the injuries it enables or permits. We have good reason to welcome capitalism. The free market does orchestrate the provision and distribution of goods and services to better effect than any system of top-down planning can accomplish.

The marriage of capitalism and democracy appears to be a match ‘made in heaven’. While democracy guarantees our freedom, capitalism delivers prosperity and rising standards of living. Nonetheless, the partnership is not without its difficulties.

There are dynamics at work in both that frustrate the other. Democracy works when it can resolve conflicts of interest, more or less, to the satisfaction of all. While there are always losers, they can hope to win through eventually. When, however, one interest accumulates powers that outweigh its competitors, the balancing act becomes more difficult.

That is what is happening now. The dynamics of capitalism generate increasing inequalities in wealth that translate into inequalities in power and influence. Capitalism’s ambitions are global. The constraints on the flow of capital are reduced, international trade is loosened, the bonds that tie capitalists to the nation-state are undone, and the power of large corporations vis-a-vis the politics that would control them increases.

Manufacturing moves from its bases in mature economies in search of the lower wages and greater profits to be found in developing economies. Those left behind, blue collar workers, face unemployment, disrupted communities, stagnating wages. The rising prosperity that once won their allegiance to the status quo is no more.

Left behinds

Horror of horrors, these ‘left behinds’ or as the university educated elites who now dominate politics and the media, call them, ’the deplorables’ , vote for Brexit, cheer on Trump, and support Boris Johnson. They are the disruptive force behind the populism we see in many western democracies.

Wolf invokes Aristotle to explain what is happening. Aristotle identified three basic political regimes. Each in its own way could serve the common good, each was prone to its own form of corruption. Royalty [rule by one] could turn to tyranny; aristocracy [rule by a few] to oligarchy; democracy [rule by many] to mob rule.

Aware of the likelihood of these corruptions, Aristotle favoured a regime that mixed aristocracy with democracy. The interest in the long term, the intelligence and competence found in aristocracy would be directed towards the common good by the constraints of democracy. It is not difficult to see liberal democracy as a version of this regime.

Political parties and the civil service provide the aristocratic element. Civil servants are guided by a strong ethic of public service. Political leaders reach the top after a long apprenticeship serving traditions with deep roots in society’s divisions. Both are motivated by the ‘rules of the game’, with its regular elections, to pursue the general interest.

Changing

All this has changed or is changing. The public sector ethos dissolves as civil servants are instructed to see themselves as managers no different from those who serve the profit motive in the private sector. Political parties no longer represent solid blocks of interest in society, their roots wither as they turn to the dark arts of spin and marketing to seduce voters.

Democratic capitalism tears apart as oligarchs intent on power and profit contend with mobs driven by the hatreds and resentments provoked by injuries, indifferent to their cause and cure.

The question: will the oligarchs defeat the mob or the mob the oligarchs? My money is on the oligarchs. After all, China appears to show that capitalism can thrive under authoritarian rule. But is either outcome inevitable? Can the dangers to which Wolf alerts us be averted?

We can argue whether or not the ‘New Right’ politics championed by Reagan and pursued by Thatcher, and here in a three-quarter-hearted manner by the now defunct Progressive Democrats, is a cause of the problems or misguided solution to deeper difficulties.

One thing is certain; its frame of reference which extols markets while evading the mutual responsibilities that attend interdependence, offers no solution. Indeed it worsens the problem.

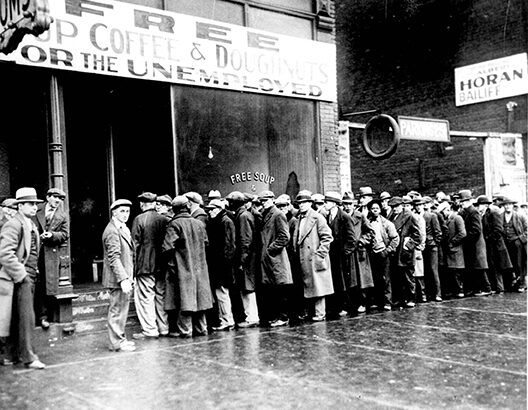

So Wolf is surely correct when he seeks a solution in the politics of ‘The New Deal’ that saved the United States from the economic depression and strengthened it for war under the leadership of President Roosevelt.

Here we find a vigorous democratic spirit determined to bend the economy towards the common good. Here we find a proactive State respected by most and supported by citizens willing to seek their interests in the context of the good for all.

What has this to do with Ireland? Our democracy is hardly in crisis. Yes, our rate of economic inequality is comparatively high and growing, but our untypical progressive taxation brings it down to comparatively low levels.

Yes, levels of immigration are high when compared with other states, yet they have not provoked the same backlash we find in many European states. Yes, the majority of voters no longer identify with a political party, which they loyally support from election to election. Our old established parties, FF and FG, weaken as they adapt to this new volatility.

But there is no evidence of disruptive populism. Is this because we skipped the industrial phase of capitalism to enjoy the benefits of the globalisation that brought the multinationals to our shore? As long as we continue to shape our mores to match their needs, as long as our governments submit to their interests, our economy will prosper and all will be well?

The United States in the 1930s depression.

The United States in the 1930s depression.