Carl E. Olson

It is something of a tradition for magazines and newspapers to run articles about the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ in the weeks leading up to Easter. Scholars, pastors, skeptics and ordinary people weigh in with their opinions.

Some argue the Resurrection never took place. Down through time there have been a number of arguments made about what really happened on that Sunday some 2,000 years ago.

Peter Kreeft and Fr Ronald Tacelli, in Handbook of Christian Apologetics (InterVarsity Press), outline the four basic theories used to explain away the Resurrection.

Theories

The first is that a conspiracy existed to misrepresent what transpired in the aftermath of Jesus’ death. The most ancient variation of this argument was concocted by the chief priests upon discovering the empty tomb: The body of Jesus was stolen by his disciples (Mt 28:11-15).

The second is that the apostles and other disciples experienced the world’s most dramatic group hallucination. Convinced that they had seen the impossible, they set out to convince the world of the same.

Another argument is that Jesus, tortured and exhausted, had not died, but had only passed out for a time until he was revived by his followers.

The final argument, which has a loyal following among atheists, sceptics and theologically liberal Christians, is that the Resurrection is a myth.

There are, of course, many problems with each theory. For example, how would a group of frightened fishermen overwhelm Roman guards and move away a huge stone?

And why would they fearlessly proclaim Christ’s resurrection and then accept martyrdom, despite knowing Jesus was actually dead? How is it that hundreds of people (see 1 Cor 15:3-8) experienced the same hallucination?

How would Jesus, who was ripped to shreds and crucified, appear shortly thereafter as glorious in appearance (Jn 20:19-29)?

Belief in the Resurrection is not a matter of mere reason or facts, but of a real encounter with the Risen Lord”

But it’s the theory of the mythical or metaphorical Resurrection that is most disconcerting.

In Acts, Peter bluntly states: “They put him to death by hanging him on a tree. This man God raised on the third day and granted that he be visible, not to all the people, but to us” (Acts 10:40).

The story of doubting Thomas (Jn 20:19-29) soundly rejects any such understanding. The Gospels describe real confusion on the part of the disciples and the fact that this confusion was due to a physical Resurrection.

“Do not be amazed!” the angel told the women, “You seek Jesus of Nazareth, the crucified. He has been raised; he is not here” (Mk 16:5-6).

The story of the two disciples journeying to Emmaus (Lk 24:13-35) emphasises how belief in the Resurrection is not a matter of mere reason or facts, but of a real encounter with the Risen Lord.

Having walked and talked at length with Jesus, they still did not recognise him. But when he took bread and blessed it and gave it to them, their “eyes were opened and they recognised him”.

“The basic form of Christian faith,” Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (the future Pope Benedict XVI) wrote in Faith and the Future, “is not: I believe something, but I believe you.”

Faith

It’s not that faith is unreasonable; rather, it is finally, in the end, above and beyond reason, although never contrary to reason. It is ultimately an act of will and love.

“We believe, because we love,” wrote St John Henry Newman in a sermon titled, ‘Love the Safeguard of Faith against Superstition’.

“The divinely-enlightened mind sees in Christ the very Object whom it desires to love and worship – the Object correlative of its own affections; and it trusts him, or believes, from loving him.”

Some argue the Resurrection never took place. Down through time there have been a number of arguments made about what really happened on that Sunday some 2,000 years ago”

Carl E. Olson is editor of Catholic World Report and Ignatius Insight and the author of several books.

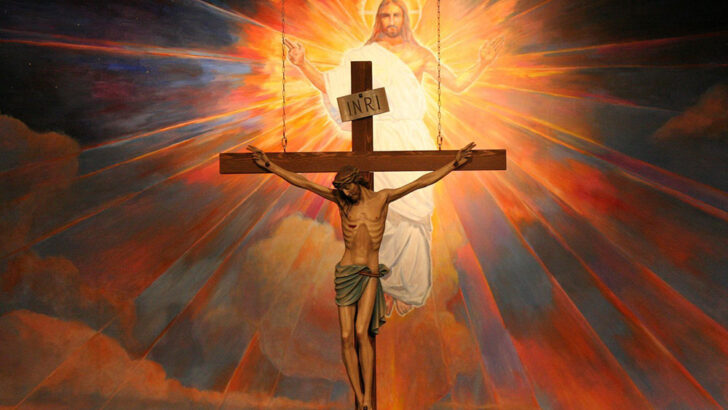

- A crucifix hangs before a mural depicting the Resurrection in the sanctuary at St Timothy Parish in Mesa, Arizona. Photo: OSV

News

- A crucifix hangs before a mural depicting the Resurrection in the sanctuary at St Timothy Parish in Mesa, Arizona. Photo: OSV

News