Laptop

by Desmond Egan (The Goldsmith Press, € 20.00 / £16.00)

William Adamson

Desmond Egan once wrote that poetry is essentially a dialogue, an insight into the universal through the particular experience, and in his latest collection, Laptop, this thought is taken to a level of intensity rarely found in poetry today.

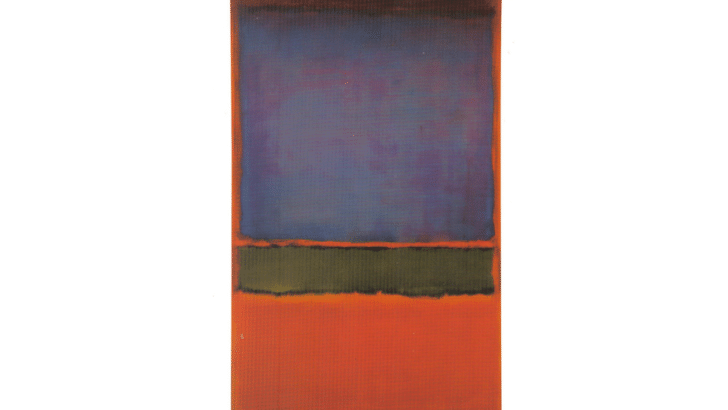

The book itself is beautifully presented with a cover illustration of a painting by Mark Rothko and in the initial eponymous poem of the collection, the writer sets out his objectives, equating the laptop with the artist’s palette, its keys (“there are bruises on these buttons / blacker than dried blood”), the brushstrokes

…. trying

like Rothko to address

life and love and it all

with music playing

The collection is divided into four sections dealing with the poet’s very personal meditations on life and faith, taking in imagery which is at once both familiar and at the same time transcending, indeed almost kinaesthetic in its ability to evoke in the reader a sense of both a physical and spiritual presence through figurative language, creating intense descriptions of actions and objects, condensing, as in the poem Pouring, the sacred into the everyday:

. . . he pours his visitor tea with

such shaking vehemence it’s as if

nothing nothing else mattered as much

nothing in the world just then

as if the meaning of everything

were there right there

God in that battered teapot

And not only in commonplace items, the poems of the first two sections also abound with images from the natural world: birds, flowers, hedgerows, animals and insects pervade, testimony of the divine in all we see. In the poem No Proof Needed, the poet dwells on the intrinsic beauty of “a forgotten forget-me-not”:

It is the world’s unclaimed beauty

God’s spare change.

Unsurprisingly, given Egan’s attachment to the poet Gerard Hopkins, there are intentional resonances, re-soundings, of the Jesuit poet’s verse and his ideas on the energy (“instress”) which gives an object its unique qualities (“inscape”). Section I ends with a poem (Summer Ends Now) acknowledging Hopkins directly and which segues into the first poem of Section II (Hunting for Hopkins), itself an epiphany of self-realisation.

Section III’s Memories comprises eighteen stanzas which are vignettes of a life lived (the “echo road”), sometimes nostalgic, sometimes melancholy, sometimes humorously ironic (“one final treat / bought bread”), all finely observed with a keen sense of self. The section ends with the elegiac line:

above the fields in blue space

one small ship

is hardly moving

slowly so very slowly

on down the vague estuary

away and

away

Section IV, Inferences, is a series of six distinct, but thematically linked stanzas. The title is well chosen and indicates, as all good titles should, the thematic direction the poem will take. “Infer” from the Latin literally means to bring or carry into, and in modern terminology would be synonymous with drawing a conclusion. In Hopkins’s imagery we might see it as the bringing in of the harvest. These stanzas address God directly and this is the most metaphysical section of the book, intensely personal and reflective:

and the poetry of a life can last

and we can catch its music

belief like that of Thomas

purified by doubt can hold

The Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke in his collection Book of Hours (Das Stunden-Buch) writes:“God speaks to each of us as he makes us, / then walks with us silently out of the night.” (“Gott spricht zu jedem nur, eh er ihn macht, / dann geht erschweigend mit ihm aus der Nacht.”), and it is this intense sense of a personal, unique relationship with God that we find in these poems.

Egan also prefaces each section with quotations from other writers. At the start of Section II he has chosen a quotation from Czeslaw Milos: “I did not have the makings of an atheist because I lived in a state of constant wonder, as if before a curtain which I knew had to rise someday.”

It is this state of constant wonder the reader is invited to share. But there is no proselytising here, simply the desire to sing openly and honestly a song of the self.

We would do well to listen. Desmond Egan’s voice is one that stands out as a major achievement not only in Irish poetry, but universally.

Dr William Adamson teaches at Bamberg University and was formerly Head of the English Department, Ulm University, Germany