EARLY PERIOD

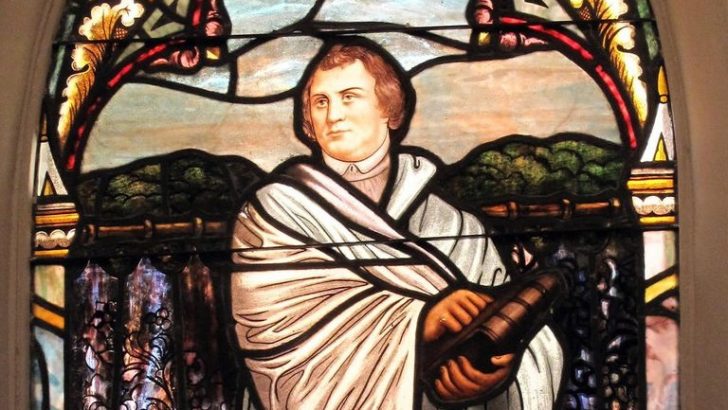

The long line of biographical investigations of Martin Luther’s life, opinions, and teachings began with the memoir written by his friend and fellow reformer Philip Melanchthon. Indeed what is thought of as ‘Lutheran theology’ also began with Melanchthon, for though Luther was a powerful preacher, and a man of strong opinions, he was not a systematic theologian.

It was from a remark by Melanchthon that the icon of the nailing of the 95 theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg church derives – the event from which many date the start of the Reformation. But this should not be seen as an act of defiance, but the standard manner of inviting debate on an academic problem in a medieval university – one might see it in a way as the period’s equivalent of a “call for papers” in a modern university.

The event played little real part in Luther’s biography, as opposed to Lutheran folklore, until the 19th Century, when thanks to several romantically inclined artists, it became the established image of Luther’s challenged to the Pope. There are now serious doubts that it ever occurred – or that at the Diet of Worms Luther cried out: “Here I stand, I can do no other.”

Part of the problem for later biographers has been to clear away the folklore and legends that surround Luther. The tale of him throwing his inkpot at the devil in the Schloss Wartburg, while he was translating the New Testament into German in 1521, is an example. The stain on the wall was long on display to pilgrims. Or rather several stains, in two different rooms, were shown off over the centuries – nothing can be seen today.

Facts

Such things delight tourists, but cannot be called ‘facts of history’. The inkpot incident recalls nothing so much as a tale of our own early saints – such as the unfortunate Furesy. It reminds us that the men of the Reformation were medieval Catholics by formation, and that they retained much of that mind set.

That translation on which Luther was working, his version in German of the New Testament (followed by the Old Testament), was an important matter. As much as the King James Version in England, Luther’s Bible had an important formative effect on how the Germans later spoke and wrote, and by extension, thought. As Goethe remarked: “The Germans were not a people until Luther.” Luther’s language and thought marked the German mind down to today, and in doing so marked the modern world indelibly.

MIDDLE PERIOD

Luther can be seen as a “dissident Catholic” (the title of Peter Stanford’s recent biography, reviewed here on June 8). But the immediate outcome of that dissent were widening circles of religious dispute, out of which the phenomena we call “The Reformation” emerged, made by the contributions of many others, notably Melanchthon, Olof and Lars Persson, Calvin, Zwingli, Knox, even Henry VIII.

Theological debate, which was what Luther wished to initiate with his theses, was overwhelmed by divergences of opinion, by the interference of emperors, kings and princes, and the resort to violence by both the peasants and by the nobles to suppress them.

Luther, fearful of disorder, took the side of the nobles. Later he retreated largely into private life. The reformation he had seemed to initiate became a developing movement with its own dynamism, which carried fractured religious opinion into areas he would not have approved of.

In this period Luther became merely a figure of propaganda to Catholics, some of it often very crude on both sides. But it meant that it was only in the following centuries that some effort was made first to set out what Luther had written and said.

The long process was begun of sifting the facts as much as they could be recovered from a mass of legendary and folkloric chaff. The emergence in the later 18th Century of the ‘Enlightenment’ altered the terms of debate, when religion became the subject of a more secular kind of investigation.

One can see one result of this in the work of the French historian of the middle ages, Jules Michelet (1798-1874), a writer who bridges the gap between the polemics and prejudices of the past and the modern historical effort to fully understand.

Michelet introduced the notion of the Renaissance – seen as a “rebirth” of classical decorum and philosophy in art and philosophy. This was in contrast to the Middle Ages, to which the term “the dark ages”, once reserved for the century or so after the immediate fall of the Roman Empire in 476 and the extinction of classical learning, but before the rise of Medieval civilisation, which was truly based in classical learning was affixed. “Dark ages” became for many Victorian writers a term of denigration for the whole Medieval era.

Morass

Michelet saw the modern world emerging from the morass of the Middle Ages through the Reformation. To him the Middle Ages were represented by the superstitions that surrounded Joan of Arc; the beginning of the modern times by Luther. But his book on Luther is very much Luther by himself, consisting as it does of an edition of his texts, rather than a full synthesis of his writings and his life.

In Michelet’s time the materials to fully understand the past from archives and from credible sources was only beginning. But his view that history should concentrate on “the people, and not only its leaders or its institutions,” has pervaded what has come to be seen today as “real history”.

His principle has slowly been applied to the Reformation over the century and a half since his death. The Reformation has become less a matter of what the leaders such as Luther and the Pope had to say, as of how new thought affected the masses of Europe and later the wider world.

In Germany perhaps the most influential study of Luther in the 20th Century was Heinrich Boehner’s biography of the young Luther, published in 1925, though it only appeared in English as The Road to Reformation in 1946. Boehner’s work was not replaced until 1993 by the work of Martin Brecht.

Boehner was the author of an earlier book investigating the matter of Luther’s visit to Rome in 1511. What Luther saw and heard in Rome contrasted with what he had believed and read about the holy city of the past.

If one were seeking a date for the beginning of the Reformation it would be this visit, and Luther’s dismay at what he directly experienced of the Papal court and its proceedings. He had become convinced that “the just shall live by faith”.

A failing of many books about Luther was that they dealt only with the early years down to the Diet of Worms and the Peasants revolt; Luther’s later years and his retreat into private life get far less attention, as they were less dramatic. But these years are now seen as very revealing in their own way of who Luther was.

MODERN PERIOD

In the immediate post-war generation, when German culture and its leaders and aberrations were being closely examined, there were three landmarks publications relating to Luther.

The first was the publication in the autumn of 1950 of Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther, by Roland H. Bainton, an Americanised Briton. Though ordained as a Congregationalist minister he preferred teaching at Yale. His biography, though well documented and illustrated, was thus from a particular point of view – it was published not by a mainstream or academic press but by a Methodist firm, Abingdon Press in Tennessee.

However, in its popular paperback edition and other forms, it is said to have sold several million copies, which might have up to ten readers a copy, and it remains in print. This was by far the most widely read biography of Luther ever written, and came at a time when the Evangelical influence over American society, which is so evident today, was beginning to exert itself.

The reviews had, in fact, been mixed. A medievalist noted that he dealt too cursorily with Luther’s alleged defects – his coarseness, for example, and his opportunism when his revolution got out of hand – a veiled reference to his siding with the nobles against the peasants, with authority against democracy. Luther’s qualities as systematic theologian are perhaps uncritically treated. A later biographer would refer to Bainton’s “brilliant guesses”.

Obsession

Luther’s “cloacal obsession”, that has formed such as source of embarrassment to both Protestant and Catholics theologians, reminds one directly of the Catholic world of his exact contemporary Francois Rabelais. As the scholar M. A. Schreech remarked, “Rabelaisian laughter is both a complement to Luther’s scornful vehemence and an antidote to it.”

Luther’s scatology reminds too us that these reformers were not middle class Americans or refined European theologians. Their lives were often rough, ready, and dangerous; their language strong, explicit, and provocative. The Catholic Middle Ages should not be judged by today’s political correctness.

In contrast to Bainton was Eric Erikson, whose Young Man Luther (1958), was subtitled “a study in history and psychoanalysis”. Erikson, an expert on child rearing and psychology, introduced the concept of an “identity crisis”. Luther who was an obedient and observant son of the Church was in reality in revolt against his own father.

This was perhaps the first psychoanalytic study of an historical person. This alone made the book controversial; but it introduced a new level of dimension into the treatment of history – one which many trained historians revolt against or still simply ignore.

Erikson suffered badly at the hands of Brinton in a damming review of his “factual errors”. Bainton thought Erikson was weak on research and a poor historian. Erikson, in turn, thought Bainton was “totally unenlightened” about psychoanalysis. Yet he admitted to a Jewish friend that Luther had “a unique role in the history of spirituality”.

Erikson’s was concerned less with “the Luther of history” than with Luther the boy and the man, with the cycle of human life as it affects all individuals.

But there was on the part of his critics a refusal perhaps to confront not only Luther’s emotional states, but also the question of the influence of individual and group psychology on historical movements. “Did Luther have a right to claim that his own fears, and his feeling of being oppressed by the image of an avenging God, were shared by others?” Erikson asked. “Was his attitude representative of a pervasive religious atmosphere, at least in his corner of Christendom?” These are questions which are still relevant.

The newer views of the reformer were given a dramatic form in one of the most celebrated plays of the 1960s, John Osborne’s Luther. Produced worldwide between 1961 and 1964, the text was widely read among the then newly emerging readers groups. Osborne is said to have used Bainton, not so much as “source”, but as a text to react against. The intense personal struggle of Luther, illuminated by Osborne’s own vigorous language, becomes here less a matter of history as of personal identity. He presented a very modern Luther.

More recently the treatments of Luther have become more varied and more nuanced. These new approaches to Luther might be summed up in the figure of the American scholar Jaroslav Pelikan, who edited the reformer’s works between 1955 and 1969. He was deeply informed about both doctrine and tradition.

For Pelikan, Luther was a single figure in a complicated picture of Christianity over the ages that he explored over the course of his long career. His own personal religious quest took him from his childhood in the Slovak Lutheran church through a friendship with John Paul II to a final adherence to the Orthodox faith.

It should not be forgotten that one of the great Catholic experts on Luther is Joseph Ratzinger, who carefully read as a young man all the writings of Luther’s Catholic years, as well as informing himself of later works. He became cautiously receptive to aspects of what his fellow German theologian had thought.

In trying to understand the meaning of the Reformation, the movement Luther initiated, his own personality and his own views and psychological quirks are not really relevant. He was not starting a “new religion”. He and his fellow reformers saw themselves as recovering the original and true faith of the Apostles.

This was summed up in the Lutheran doctrines on faith, grace, and scriptural foundation, Luther’s three solas: Sola Fide, Sola Gratia and Sola Scritura. Lutheran theologians believe the brokenness of humanity and of individuals can only be healed by the Grace of God in Jesus Christ, and can be received only in Faith, which is nourished through the study of and reflection on Holy Scriptures.

Ecumenical times

We now live in ecumenical times. In 2016 the conference of German Catholic bishops wrote of Luther as a “Gospel witness and teacher of the faith”, calling for closer links with Lutherans and other Protestants. Bishop Gerhard Feige, their chairman, said that “the history of the reformation has encouraged a flexible reception in the Catholic Church, where its events and protagonist were long seen in a negative, derogatory light.”

Bishop Heinz Algermissen spoke of “healing memories”, of the Churches working towards not just reconciled diversity, but a visible unity. “This means not only praying together, but meeting the challenge of speaking with one voice as Christians when we are all challenged by aggressive atheism and secularism, as well as by [radicalised] Islam. Otherwise we will lose more and more grounds.”

Anyone wanting an accessible overview of the beginning of the Reformation and the role of Martin Luther will find Peter Marshall’s 1517: Martin Luther and the Invention of the Reformation (Oxford University Press, £16.99) an ideal read. The author is a recognised authority on the Reformation as a whole, both across Europe and in England. The book is designed to explore what was thought about Luther at the time of the previous centenaries, and how his presentation changed.

At first in 1517 what was involved were responses. After all the publication of the theses was an invitation to debate, not a creedal statement. Responses from the Church authorities and from those who supported Luther began to form divergent traditions. By 1617 the date was celebrated only as an anniversary, but by 1817 Luther had emerged as a hero (as he was seen by Carlyle). But by the ominous year of 1917, another world-wide movement was beginning, that challenged Reformation in a new way.

Of course, as the author concludes, we have no such thing as ‘The Reformation’, a single organic entity, but ‘reformations’, with a more detailed view of their various strands and conflicts and personalities. This is altogether an excellent book, not only for those who wish to learn something about the start of a movement, but also how today we try to come to an understanding of what history was, is, and can be.

This book can be recommended especially to those who are dismayed that ideas about what happened in the past keep changing, as well as those who wish to promote the greatest possible understanding between Christians separated by those changes.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello