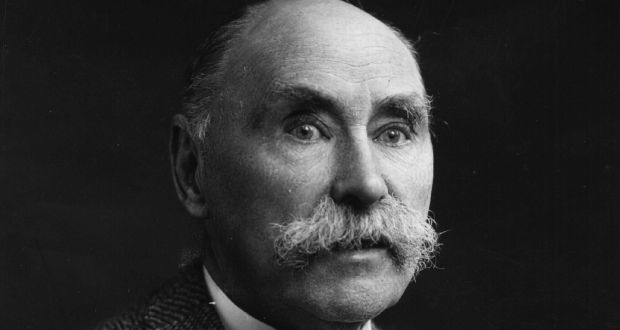

Douglas Hyde: A Maker of Modern Ireland

by Janet Egleston Dunleavy & Gareth W. Dunleavy (University of California Press, £48.00)

Douglas Hyde/Dubhlas de hÍde served as Ireland’s first president from 1938 to 1945.

This was the very highest distinction which the new state and the people of Ireland could bestow. Hyde himself was a man who had been one of those shaping Irish culture since the 1880s. He had been all his life a scholar, never a politician, never a lawyer. He set a headline for the position which has not always been followed since.

He was born on January 17, 1860. His father, Rev. Arthur Hyde, was the Church of Ireland rector of Kilmactranny, Co. Sligo. A few years later the family transferred to the Manse at Tibohine, near Frenchpark in Co. Roscommon. After an unhappy experience at a prep boarding-school in Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire), Co. Dublin, Douglas was educated at home by his father.

Douglas entered Trinity College, Dublin, as a divinity student in 1880 and graduated with a BD in 1885 but did not proceed to ordination. He continued his studies and was conferred with an LLB in 1887 and LLD in 1888 but never practised. Disappointed at not securing an academic appointment in TCD, he spent a year teaching English in the University of New Brunswick in Canada.

Fascination

Douglas had a fascination with, and a gift for, languages. From his earliest years by chatting with his neighbours he acquired a mastery of Irish. He also exhibited an interest in antiquarianism, poetry and nationalism.

He joined the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language in 1877 and the Gaelic Union in 1878. From 1879 onwards he published numerous Irish poems under the pen-name ‘An Craoibhín Aoibhinn’ (‘the pleasant little branch’).

Douglas became president of the National Literary Society in 1892. His inaugural address ‘The necessity for de-anglicising Ireland’ argued that political nationalism, however necessary, had, by propagating itself through English language media and drawing attention to debates at Westminster, blinded the Irish people to the fact that they were losing their national identity along with their language.

He declared that the loss of the language had left the Irish people culturally impoverished and degraded. Hence it was essential that they recover their identity by reviving the Gaelic language and re-establish contact with their ancestral traditions.

The lecture inspired the formation of the Gaelic League in 1893 and Douglas became its first president. He proceeded to publish extensively in Irish: folk tales, poetry and plays. His Literary History of Ireland treated exclusively with literature in Irish and claimed that the works of Irish writers in English could not properly be called Irish literature.

Douglas was professor of Modern Irish at University College, Dublin, from 1909 to 1932 and during that time was an active supporter of every organisation promoting Irish throughout the nation.

As early as 1899 he was a leading figure in successfully blocking the attempts of TCD academics to remove Irish from the school curriculum. He was again to the fore in the successful Gaelic-League campaign to make Irish compulsory for matriculation in the National University of Ireland.

He served in the Irish Free State Senate in 1925 and the re-constituted Seanad Éireann in 1937. Following the ratification of the new Constitution, his membership of the Church of Ireland and non-party-political status made him a popular choice to act as the country’s first president.

In the event he fulfilled the role admirably and established important precedents by referring controversial legislation to the supreme court and by taking advice from his staff before granting a dissolution of Dáil Éireann.

Douglas married Lucy Cometina Kurtz, a wealthy English woman, in 1893. A few years after their marriage she became a chronic invalid. One of his two daughters died prematurely in 1916. He suffered a stroke in 1940 and died on July 13, 1949.

As early as 1899 he was a leading figure in successfully blocking the attempts of TCD academics to remove Irish from the school curriculum”

Douglas Hyde was one of a select few who made a crucial contribution to initiating and promoting the evolution of the New Ireland. It is ironic that just two incidents from his life-time of public service seem to remain in the public memory.

The first is his resignation from the Gaelic League after the ard-fheis voted to make it a specifically nationalist organisation in 1915. The second is his expulsion from the GAA, of which he was a patron, for contravening the organisation’s rule banning foreign games after he attended a soccer match between Ireland and Poland in 1938.

As an envoi, may I say that one practical way to deal with such a deficit of knowledge and appreciation of an outstanding patriot would be to place this excellent biography on the reading lists of the history courses in our secondary and tertiary colleges.