By the Books Editor

Into Iraq

by Michael Palin (Hutchinson-Heinemann/€19.99/ £16.99)

Having abandoned the Python squadron, Michael Palin has created a new strand to his life making travel documentaries. In his new book, which deals with a long-intended journey through Iraq, he admits to feeling the effects of what we can kindly call his mature years, but there is nothing OAP here at all.

This month marks the 20th anniversary of the Iraq invasion by the allied forces of the United States and Britain, an adventure that went very badly wrong. It cannot be overlooked that the invaders allowed some 12 billion dollars simply to disappear, money which it admitted was not US government money, but Iraqi money by right. The corruption around all this set the tone for the decades to follow. And the activities of the Halliburton company linger still in the memories of many.

Michael Palin began his journey at the source of the Tigris in the mountains of eastern Turkey, and followed the river south to the Persian Gulf. The trip was a fast moving one, over some 18 days in March last year.

They say that to get the essence of a country one has to either spend 20 days in a place, or 20 years. Palin, in this book, is of the “few days school” of inquiry. But though he lingers nowhere for long he actually saw and experienced a lot. At journey’s end he says: “I’m glad I went to Iraq and I would go back, for the one reason that I met many good people there and I should like to see them again.”

There are those like myself who are paralysed by the name Mesopotamia. It is a term that carries a heavy burden of myth, legend and history from the emergence of Sumerian culture about 5,000 BC, a date which carried all too many echoes of Archbishop Ussher and the date of creation for Christians.

But Palin wisely skates lightly over this long past, and rightly so, for it is all too easy to wallow indulgently in prehistory and history, as so many did in the past, and neglect to observe or even talk to the people who have the very different burden of living in the decaying country today.

In the upper reaches of the Tigris Palin talked to a local man who complains that the government – “those people down in Bagdad” – is more anxious to come to terms with foreign powers about oil, rather than secure the water supplied to the country by dealing with the Turks. Water is in fact more critical to the people’s future than the oil, but oil is wealth for those in power: a typical tale of modern times.

I greatly enjoyed the ever changing vignettes of a people trying hard to create a better future for themselves their children and their grandchildren. He visits Ur, and sees the famous ziggurat, but very oddly says nothing at all about Abraham, who is their founding patriarch for Muslims, Jews and Christians. With him, in a sense, begins the religious discord in the region. This is a strange lapse by an Oxford graduate: has he forgotten his Sunday school lessons, one wonders? And it says a great deal about the level of awareness of the past in modern Britain.

However, Palin makes up for this lapse with a visit, on day 16, to Al-Qurnah. This is where the Tigris mingle with the Euphrates, to become the Shatt al-Arab; and there in the public park is a very ancient tree, blessed by Abraham it is said, which a large handcrafted notice claims is “Adam’s Trees”, the very tree mentioned in Genesis (2), the fabled tree whose fruit gave Adam knowledge of good and evil, and the difference. This shaded grove is now a popular place to play dominoes or to talk.

But it is also a symbol of modern Iraq, which could with proper conservation of water again become the green paradise it was in ancient and medieval times, but that requires a command of knowledge and an avoidance of evil, and both of those are hard to achieve not only in Iraq, but anywhere is the world.

Though swiftly paced, this is an enjoyable and illuminating book, which will instil in every reader high hopes for the future, a future one hopes with less oil and more water.

Peter Costello

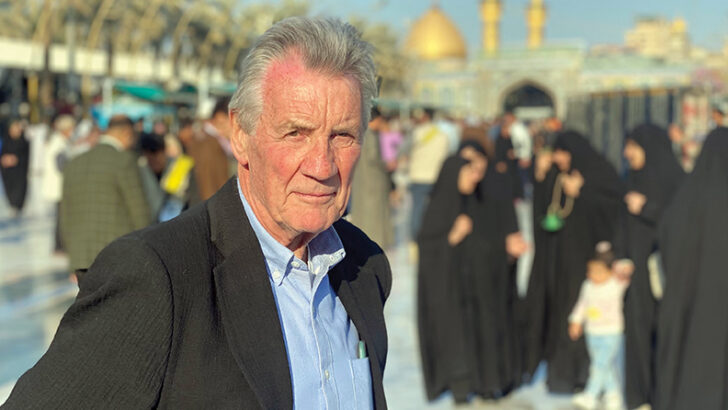

Peter Costello Michael Palin tasting the coffee house culture of Iraq today.

Michael Palin tasting the coffee house culture of Iraq today.