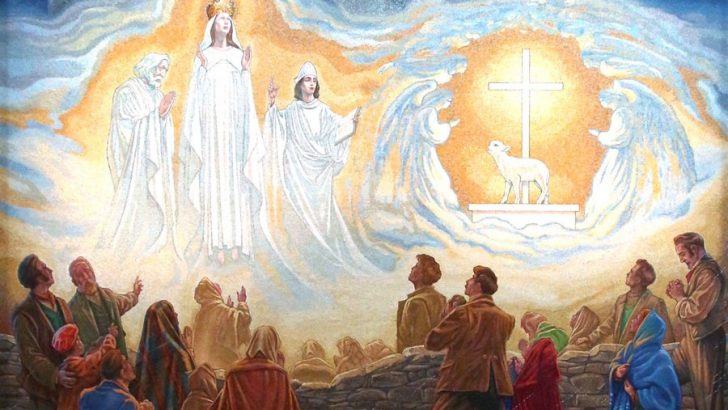

Even for those who don’t know his name, few artists in today’s Ireland are more closely linked with Christmas than Belfast-born PJ Lynch, recently the country’s fourth Children’s Laureate but perhaps best known to readers of The Irish Catholic for his work on the mosaic of Knock Basilica.

2016 and 2017 saw his delicate watercolours gracing the covers of the Christmas editions of the RTÉ Guide, while anybody who has set foot in an Irish bookshop over recent weeks will have found themselves faced with piles of his heavily illustrated editions of Oscar Wilde – Stories for Children and Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol.

“I had done A Christmas Carol as a college project when I was a student, and I had done four pictures from it,” he says. “I always loved the book and years later I thought ‘You know what? I’d love to do a full illustrated version of this.’”

He took the idea to his publisher, who proposed that instead of doing an abridged edition of the text, which would have been the typical publishing approach of the day, they should do the entire story, which would require 85 illustrations altogether.

“It was a big project, but it was such a great one to be involved in. I look back on that one, and I really felt that was just such a great story – I love the story, I love the fact that it came from me, and the art in it I’m really, really proud of. I think it stands up well.”

Seasonal fixture

Published in 2006, it was by no means his first Christmas book – the snow scene on the front cover of his 1990 Oscar Wilde book had first installed him as a seasonal fixture, but it was 1995 Kate Greenaway medal-winning The Christmas Miracle of Jonathan Toomey, written by Susan Wojiechowski, that firmly lodged him in that role.

“That’s been my best seller. That’s sold almost three million copies – it’d be good if some of my other books sold as well as that,” he laughs. “It’s a brilliant story, a lovely, Christmassy, heartrending story.”

Cartoonish art is perhaps the norm in the world of children’s book illustration, but while the Brighton-trained artist is unsparing in his praise who’ve made their name with that approach, it’s clear that he’s committed to his own more classical approach.

“I suppose my style of work is, you might say, traditional, representational, naturalistic,” he says. “There’s not too many artists in the picture-book world doing naturalistic stuff. There’s a lot of cartoonists, there’s a lot of ink and wash people like Quentin Blake, but that never excited me a whole lot.

“I like Quentin Blake’s work as well, and I think he is very well suited to Roald Dahl, and I suppose the publishers felt it’s a winning combination so let’s keep the two of them together, but the kind of books that I’m doing are probably aimed at older kids or maybe – I don’t know how to put it, but they’re certainly aimed at bookish, thoughtful kids, and sometimes the subjects are kind of dark and serious.”

While he says he likes doing funny stuff too, he doesn’t get the chance too often.

“A lot of my books are about serious subjects like death, and loss, and coming to terms with those and hopefully finding a way out in the end, so it needs a sort of serious approach to the illustration to match that type of text,” he says.

The Christmas Miracle of Jonathan Toomey is perhaps his book that most obviously fits that description, but his approach pays off too when accompanying the epic tales of Irish myth in Marie Heaney’s The Names upon the Harp, where his illustrations rival those of Alan Lee in his 1990s illustrations for Rosemary Sutcliffe’s retellings of Greek legend, and for Tolkien’s work.

“He was one of my absolute heroes when I was a young illustrator, and I’d just look for his next book – his technique was so wonderful,” says PJ. “I think you appreciate his type of pictures in a way that you don’t with the jokier cartoony stuff. With the jokey stuff you look at it, you get a laugh, and generally you move on pretty quickly – it’s about progressing through a book very rapidly, but with someone like Alan Lee who does absolute masterpieces of illustration, you can dwell on the picture and you can absorb the atmosphere and you can look for detail that would help you into the story, and that’s more the approach that I would take myself.”

Other illustrators’ names pour off his lips as he raves about artists whose work he likes – the Russian Gennady Spirin, the Austrian Lizbeth Zwerger and the young English illustrator Levi Pinfold – as well as more classical artists like Alphonse Mucha, whose 20-part Slav Epic has long been on his ‘bucket list’ of things to see.

“When I was a kid I used to love Leonardo particularly, and then Michelangelo probably second to Leonardo for me – they’re just giants,” he says. “Now, when I approach my own paintings I wouldn’t be directly thinking of them, but they certainly were my inspiration for many years when I was a youngster.”

Mentioning Michelangelo of course brings his work in the Sistine Chapel to mind, and PJ exclaims how one of his own works is now in the Pope’s possession.

“You know he was in Knock, and I did the Knock mosaic? Well, before he was coming over they said they wanted to present him with a replica of the Madonna’s head from that,” he explains, adding that it had to be redone on a slightly smaller scale, so drawings and photographs were dug out and he set to work, tweaking aspects he wasn’t quite happy with.

“I couldn’t resist! Fixing bits, and you know. I was working with the mosaicists and they told me when they needed it, so I did it, fixed it up quick for them, sent it over, and they made it up for him,” he says. “I don’t know if he liked it or not, but he sort of looked admiringly at it,” he laughs.

The original commission for the mosaic at the shrine had come about through life drawing sessions he’d been going to, he explains.

“I used to go to a life drawing session at the United Arts Club, and you get to know people there and you’d have a drink afterwards, but I never got to know too much various people, just have the craic,” he says.

“And then there was one of the guys, I got a phone call from him, and I knew who it was but wondered what it was about. And he explained that he’s an architect – and I’m sure it must have come up before – and he says we’re looking for someone to design a mosaic for a religious building.”

Assuming the mosaic would be on the floor, and probably about two metres across, PJ had said yes, he could do that.

“So he said well, come in and see us,” he continues. “So I came in and there were three or four architects around the table and they had these printouts showing a mock-up of what the refurbished basilica would look like, so I had to pretend not to be shocked or stunned that they were talking about this huge big space on the wall behind the basilica’s altar.

“Again I sort of just bluffed my way through it and said yeah, I could do that.”

He had done big pictures before, notably illustrations from Gulliver’s Travels for Cavan library, but nothing on the scale of Knock, but he set to work.

“I started into the whole process of designing it, and they really liked the ideas I came up with so they stuck with me. I presume there were other artists that they were talking to. I think they invited me to pitch for it because I’m an artist who tells stories with pictures and that’s what they wanted on the wall,” he says.

“I think that was kind of unusual, because a lot of Church art these days – I think people are very concerned about looking as if they’re up to date with the art world, and an awful lot of artwork that goes into churches, certainly when I was a kid I remember nobody in the congregation liked the work! But the arts committees had gone through the motions – you know about art, tell us who should do this, that kind of thing.”

At the heart of the Knock commission, though, was the need to tell what happened. “The Knock people said, look, we’ve got this great story and we want to tell it in a picture,” he says, adding, “It was a super project.”

A regular point of reference for him was the shrine’s Apparition Chapel, with its marble sculptures carved by the Italian Prof. Lorenzo Ferri in the early 1960s, with the shrine administrators wanting to acknowledge a continuity with the previous work, carried out under the watchful eye of Dame Judy Coyne.

“I think they’re absolutely lovely,” PJ says of the statues. “Though the poor man was working away and sculpting away and couldn’t get the lamb to her satisfaction, and eventually he said to her, look, go out to the market and get me a lamb that looks the part and I will do it. And she did it. And she stayed out there for months just keeping an eye on him, and he eventually had a heart attack, he was so stressed out, poor guy.”

He felt something of a kindred spirit with Prof. Ferri, he adds, because of the amount of back and forth required in designing the mosaic.

“This is something to do with religious art that you don’t get under other circumstances,” he says, likening it to ad work in a sense because of how it tends to be directed by a committee with various interested groups. “It’s a bit like that – it’s nothing like kids’ books where you get a lot more freedom. But I don’t mind it.

“As a child, like I said, I loved Leonardo and Michelangelo, and Harry Clarke, and if you’d asked me what I’d love to be doing when I’m older, I would have said that kind of art, so there’s good sides and bad sides to it.”

His original design was a large oil painting, but watching his work be transformed into a huge mosaic was a remarkable experience.

“I worked with the mosaicists, and I appreciate the limitations and the qualities of mosaics, because you get this shimmering magic about it, because it shines and a lot of it is glass, so there’s stuff happening that doesn’t happen with oils or with watercolours, and the downside is that it’s a little bit more primitive, you can’t get the exact, perfect edges,” he says.

“But I was knocked out by the work – these guys are just…you can’t call them artists, they won’t let you call them artists, they call themselves artisans, Travisanutto in Spilimbergo. They were such a pleasure to work with, anything I had a problem with they worked out and changed while I was there super-quick. I’m really happy with the finished result.”

Even now it’s clear that the full-size mosaic dazzles him.

“It’s nice to see it in the flesh – the height, it’s the height of a five-storey building,” he says. “It’s unbelievably big, and to see these figures who on my first drawing were three inches, four inches. My concept didn’t change that much from the start to the finish, and the figures of the witnesses were really important to me. That’s where I got the freedom that I didn’t have with the apparations.

It was, he says, his idea to have the witnesses included in the image.

“I wanted the witnesses to be there, I wanted them to be the bottom third of the picture – we squashed them down a bit. Because that’s a way for the congregation in the basilica to relate to the picture and to feel their way into it, and it worked especially well when they were unveiling it.

“They had actors on stage – when you look at it in a certain way you get this sense of depth: the people in the congregation, the actors on stage, the figures at the bottom of the mosaic, and then the apparition. It works in stages. I couldn’t be more pleased with the way it came out.”

Given how he’s been responsible for surely the highest profile religious artwork the country has seen in many years, it’s hardly surprising that other religious commissions have come his way, and when I visited him at his Dublin home he was working on two altar pieces for St James’s Church in Kilbeggan, Co. Westmeath.

“I was given the themes,” he says. “That’s the Holy Family in the carpenters’ shop, and they specified that Jesus was to be about 14, rather than younger, and the other was ‘Suffer the Little Children’, and those subjects really appealed to me, so I was delighted to do that.”

Greg Daly

Greg Daly The mosaic at Knock Shrine

The mosaic at Knock Shrine