Curator for the NGI: Anne Hodge. This exhibition is organised in cooperation with the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. 16 July – 6 November 2022; Print Gallery | Admission free – no booking required

An appreciation by Peter Costello

The Print Room in the National Gallery is a shaded coign which in an almost retreat-like atmosphere creates a mood of relaxed enjoyment.

It is very well suited to showing these drawing from the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. It is one of the great galleries of the world, a place everyone should try and visit. The present show is centred on a collection of drawings, and they reveal the nature of Dutch art in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Holland is a low-lying country whose whole existence derives from the control and use of water and land. There are no spectacular landscapes, no great cities in ruin or partial ruin, no sense of dominant majesty. The scenery, in the rural parts, is of rivers, canals, farm houses, lonely trees, occasional woods. But the true character of the people is revealed in the towns and cities, and their art is one of intimacy, of private life, of the interest of individuals for themselves.

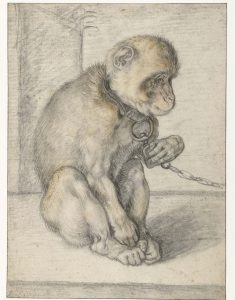

All of these aspects can be seen in the 50 drawings on display. Even the religious scenes such as Ferdinand Bo’s Christ Appearing to Mary Magdalene as a Gardner, Rembrandt’s Annunciation to the Shepherds, or van Hoogstraten’s Incredulity of St Thomas have a small-scale intimacy. But it is the living, closely observed detail of ordinary life and animals that especially strikes the visitor: a calf lying down, a monkey on a chain, the defiant head of a goat, an artist at work on a woodblock, a woman spinning, an old woman with a cap. The exhibition has chosen to promote itself with a striking image of Rembrandt’s self-portrait wearing a black beret looking out at the world wide-eyed.

Wealth

However, though this was the age when the wealth of Holland was being built up through activities around the world of its sea-borne empire, domestic life was not forgotten. This privacy is still a feature of Dutch life.

Yet if there is one images that I carried away in my memory it’s Gerard ter Borch the Elder’s Portrait of a girl reading a book: doubtless this might be thought to have been a devotional work, though perhaps not, but the record of a petty bourgeois girl owning and reading a printed book, for amusement or improvement, epitomises a whole era in Northern European culture after the introduction of printing. The drawing is evidence of a massive revolution in world culture.

These may be small images but they are filled with profound reflections on life as lived.

As the curator says, “From a child’s first steps to peaceful wooded landscapes, Dutch Drawings gives an insight into life in the Netherlands centuries ago through exquisitely skilful works on paper”.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello Gerard ter Borch the Elder (1583-1662): Girl Reading, early 1630s;

pen and brown ink, brush and brown and grey ink, red chalk. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Gerard ter Borch the Elder (1583-1662): Girl Reading, early 1630s;

pen and brown ink, brush and brown and grey ink, red chalk. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.